March 22, 2018

I should in theory be waking up in my luxurious hotel room feeling incredibly energized, but nothing could be further from the case. How could that be? Well, continually getting far too little sleep, trying to squeeze a meaningful written discourse out of those tired and/or lazy brain cells every night, particularly under the influence of alcohol, doesn’t help much. But why is my back out?

Emerging from my room, I am greeted by a tranquil paradise around me, the surrounding forest an encapsulation of the natural beauty of the region. Walking towards the main building with the restaurant, I hear very loud squawking the bushes above, which turns out to originate from one or more Colombian chachalaca, a very unusual and also unusually raucous local bird.

Breakfast should be a pleasant affair, but I make the mistake of telling the hotel manager that I slept poorly, and suspect that the mattress in the bed isn’t very good. He is mortified, as the quality of mattresses is regularly verified, and noone has ever complained about the quality of their sleep. I should have kept my mouth shut, particularly since the problem with my back stems back to the deplorable place I was staying in in town.

But now he becomes fixated on the subject. To be frank, no, the mattresses are not great, but it simply won’t be possible to get high quality mattresses in the country, and then why would you in this kind of hotel, anyway? The hotel may represent the paragon of luxury locally, but is a low budget boutique hotel that simply won’t have the budget to spend on luxurious mattresses. How about a Hästens Vividus mattress for $150,000?

It is imperative that I be ready by 9 am, as that is when the tour I am scheduled to join will be appearing at the hotel. And on time the driver/guide is, the manager’s daughter and her friend from Indiana joining in, our vehicle continuing on the road into town to pick up a young Argentine couple I had spotted at the archaeological park yesterday. Then we are off on the road to Isnos to take in the attractions, my conversation focusing on the guide, somewhere jovial and yet also bearing the measured demeanour of someone who spends far too much time dealing with the public. The two young women chatter excitedly with each other, not seemingly very interested in the world we are exploring, and the Argentine couple chattering excitedly with each other.

I am not just covered in ghastly-looking bites, but they are particularly painful. I have no idea where I could have gotten them, and they appear to flea bites, rather than mosquito bites, given that they are covering only the outside of my right leg. Hopefully they will heal soon. To be on the safe side, I will cover the leg with an antibiotic cream.

The road to Isnos doesn’t have the look and feel of the road to Obando, the landscape more open, less forested, more generic in feeling, with more settlements, and in general more touched by the human hand. Our first stop is the Salto del Mortiño waterfall, which we take in from a small finca, strolling along the side of the cliff, looking down over the jet of water cascading far in the distance into the canyon deep below, the wheeling flocks of parakeets framed against the waters churning at the bottom of the canyon. My fellow visitors are somewhat wary about walking onto the covered platform extending a few metres over the open canyon, a sentiment I share, if only with respect to my camera, which I can imagine falling far below to its inevitable doom as it slips out of my hands. Now I just wish I could get better shots of the parakeets …

I am not sure why we paid COP $2,000 pesos as admission fee – it’s not as if the finca owns the land the waterfall is located on. Sure, we have to access their land to look at it, but then they also operate a small shop, selling snacks and trinkets to visitors. You take what you can get …

The Argentine couple remains on the terrace of the small shop to sip their tinto, which looks fairly watery. I ask the driver if there is any possibility of stopping in some appropriate place for a good coffee. ‘Most of the coffee served publicly in the country is of poor quality’ he sniffs, disappointedly, but then counters that he makes his own special coffee that is of the most exquisite quality, and that we will be able to savour, not just once, but three times during the day. I am thrilled at the prospect of being able to take in the aforementioned experience, although in the end he never prepares any coffee for us.

The Argentines are considering visting the Desierto de Tatacoa, which automatically brings out a somewhat virulent reaction on my part. The services offered in the desert are very substandard and it is very hot, so best stay in Villavieja. The guide is not particularly pleased with my exposition, and later diplomatically counters that if I have an issue with the area, I should publish my views in social media. What’s more, there are good gastronomic and accommodation options in the area, you just have to know where to go.

Fair enough – but when the public transport drops you off in front of some tawdry hostel, and there are only similar places in the vicinity, what is a visitor to do? And if the accommodation options are dispersed in the desert, how are you supposed to find out about them, or even reach them as a casual visitor? Why should it require such a degree of organization?

We drive all the way to the Salto de Bordones, which I am eagerly wanting to see, given that it is apparently the second highest waterfall on the continent, somewhat of a reputation to live up to. For a waterfall of such a spectacular height, I would expect the landscape towards Isnos to become more mountainous and dramatic, but it looks utterly pedestrian at best, perhaps somewhat like an average day in Boyacá. We continue onward, and are rewarded by the appearance of the singularly ugly town of Isnos, a far cry from the pretty serenity of Obando.

The guide dismisses the town as a haven for uncouth and uneducated frauds, which seems somewhat excessive, as we gape out the window of the vehicle into the uninspiring bleakness of its streets. We continue, weaving along the narrow country road running along the escarpments and hillsides towards the town of Salto de Bordones, through the town and along a country lane to the parking area of a small boutique hotel – but where is the waterfall?

Approaching the edge of the parking lot, there it is, far below us, a huge waterfall cascading downwards into a chasm beyond our view. The earthen-toned ridges rise high up across from us, a string of small trees lining the ledges of the escarpments, the outline of more distant peaks visible beyond. And yet judging by the general topography of the land around us, it seems difficult to believe that the drop beyond our sightline could be that profound, and hence the waterfall remotely as high as we have been told. At least the boutique hotel set at the edge of the precipice offers an unusually posh experience in an incongruous setting, with its small, pretty floral garden, sharp, modern furniture, and incongruously, droning meditation music emitting from a speaker on the ledge facing the waterfall below.

And now onto the first cultural destination of the day, the Alto de las Piedras, which is one of the two archeological sites the entry to the Parque Arqueológico De San Agustin also grants admission to.

I take endless shots of the statues in the park. As with all remaining sites in the area, by the time archeologists began their work, most of the contents had been pillaged by looters. The site is largely dedicated to funerary sites over which preside large abstracted figures in the typical San Agustin style, with bulging eyes, a distant gaze, and hands clasped over the abstracted body. A large part of the appeal of the site is of course the lush greenery that erupts from all sides of the perfectly manicured lawn area.

Beyond the totemic quality of one the larger figures is the reptilian figure carved onto the side of the large statue, standing in front of a deep pit which presumably represents the actual burial pit, flanked by large slabs of stone. The stones are bereft of any adornment, although apparently, were originally painted with bright geometric patterns. The slabs of the encasing tomb were decorated with geometric motifs painted in black over a red background.

At other grave sites, small figurines stand guard at the entrance, flanked by dolmen-like slabs, the rows of teeth bared with bulging eyes protruding in a garish grimace, the angled arms gripping onto what looks like an erect penis. A dose of fertility en route to the afterlife? Another more elaborate figure features some sort of cap, flared nostrils, and gripping what looks like a short sword.

The canopied grave sites are arranged around the periphery of the manicured field, set on a small plateau above the road. The cloud cover above us remains inert, our visit bereft of rain, despite the threat emanating from the clouds above. As with every other site we visit, there are only a few other visitors, also being ferried around by local guides.

Given the relatively limited form of expression found in the San Agustin statuary, it is worth noting that there are variants in girth, arm size, facial features, head dresses, and jewelry that give rise to questions concerning the reasons for the variations. Client-related requirements? Symbolic significance? Artistic license perhaps?

I had originally planned on visiting the waterfalls and archaeological sites around Isnos independently, but given the distance of some of the sites from the main road, there is no way I would have managed to do so on my own, unless I left early in the morning and spent the better part of the day walking – and hoping that it doesn’t rain …

The guide had suggested taking us to a granadilla plantation, which seems like a great idea. I have been peppering him with questions regarding the crops being grown in the area all along, and so we may as well visit some place where agriculture is in full swing. And the granadilla is definitely in full swing, hanging off trellises similar to those used to support grapes, the plum-like greenish-yellow fruit hanging individually or in small clusters off the trellises, erected along the slope.

We are offered individual fruit that we pick for 500 pesos a piece, which I find somewhat ridiculous. In Colombia, in the middle of nowhere, you are offering to sell us fruit that we pick at 500 pesos a piece? The young woman who seems to be the human face of the operation is utterly indifferent to our presence, one more reason to let her keep every last one of the granadilla hanging off the vines and find a more inviting environment to spend our time in.

The guide may not be a big fan of Isnos, but it is the only place we can get any kind of reasonable almuerzo. The quality available in town is largely disappointing, but at least the restaurante tipico we are deposited at in this non-descript area of an utterly non-descript excuse of a town is capable of serving a reasonable quality. And the quality is reasonable, but no more than that. But where has the driver disappeared to? The act of walking around the corner towards the market becomes a major social event for the bored locals, calling me into their businesses.

Matters escalate when I wander into the market to buy some fruit, ‘a la orden’ cascading from the mouths of the vendors around me. I finally land on one, who despite her hard sales job manages to hand me a bag of half-rotten lulo, which even I am aware enough to catch. Do I look like that much of a sucker to you? I keep the crowd gathered with random quips, and when I return to the jeep, the guide has also returned to take us to the next attraction, the Parque Alto de los Idolos.

A major trek uphill awaits us to the Alto de los Ídolos. A few vendors call the limited number of visitors to savor their edible wares or buy some of the more lasting merchandise, which could be appealing if it weren’t for the fact that virtually the same dross is sold everywhere else in the country, with the exception of the tacky copies of the statues that litter the archaeological sites in the area. The coffee one vendor insists I taste is too bitter for my liking, despite the guide telling me that he taught the vendor how to make coffee.

The steep path rising up the artificial mountain is lined with exotic flowering bushes and trees bearing identifying signs, including rubber, guava, trumpet trees, cucharo, guamo macheto, arrayán, and so on (I have include common Spanish names in lieu of Latin names in some cases). Of course, I take my time climbing up the hill, looking at every plant, tree, bush, flower, not taking into consideration that there is an unspoken allotted time for the intended visit, which I dramatically overstep.

Alto de los Ídolos occupies the crest of a hill to the far lower end of the escarpment, the manicured lawn on which the canopied grave sites are situated arcing across the open space, the thick forest closing in at the edge of the golf course-like setting, the blue-grey shadows of the distant hills beckoning as the skies finally threaten to unleash the promise of rain, although in the end we are subjected to no more than a casual sprinkling.

Consistent with the sites we have visited yesterday, the statues at Alto de los Idolos are similar in form and expression, sheltered under canopies, often juxtaposed with funerary sites, graves, dolmen-like slabs of rock, erected at vantage points situated across the face of the manicured lawns. Surreal, gaping expressions, bug eyes, tiny arms clasping some indeterminate object all figure in the compositions. A few humans straggle across the field, the clouds building overhead, the trickle of rain threatening to erupt into a massive downpour. The fecund forest set on the edges of the impeccably cut lawn on which the statuary is situated is in turn framed against the crests of the hills disappearing into shades of grey in the distance.

Giant statues stand sentinel toward the centre of the grounds, impassively staring into the distance. Of the smaller funerary sites located on the crest of the hill, small figurines evoke images of howling children or monsters bearing phallic weapons. In place of humanoids, reptilian creatures guard grave sites, the heavy stone slabs enclosing the graves to the rear or below. Exceptionally, one grave features a mute figure laid out in the rectangular pit, staring mutely towards the sky. Elsewhere, heavy slabs crown the squat, grimacing figures guarding their lot, flared nostrils and angry eyes in stark counterpoint to the small hands, nervously clasped over the small bellies.

This much larger site is similar to the others, although more dramatic, the very hill on which the bulk of grave sites are located artificially amended presumably to provide a more prestigious location for those departing to the world beyond. Statues consistent in expression and form with the San Agustin style stand guard at dolmen-flanked graves of varying sizes. Varying amounts of domestic goods as well as jewelry found in some of the sites would denote the importance of the buried party in the society at the time.

We cross over to Obando by means of a road that passes through the mountains, although it may have been a better idea to simply return via San Agustín, given the seemingly interminable waits for road work to abate and let us pass. Thankfully, it isn’t raining, otherwise large stretches of the road would be reduced to a mud bath. It seems difficult to believe anyone is relying on these treacherous roads.

At the initial stop, the group of schoolchildren on motorbikes looks at our vehicle excitedly, the foreigners a perennial source of entertainment for locals. At the second and by far the longest, the sign person is all smiles, from our cynical world, but then she gets paid the same no matter how long we wait. For that matter, these road improvement projects seem to be unfolding in an inappropriately artisanal manner, and it’s just as well I don’t have to retrace these steps.

It seems incredible that these regions were all quite unsafe until a few years ago. Now, it all just seems like a bucolic and welcoming paradise …

Since we have little to do, other than wait, the guide lists the names of plants and trees he can remember that he would have passed. The list is long including tree fern, avocado, guava, boquila and of the flowering bushes and trees, violet, tibouchina, frangipani, yellow aster, tropical sage, chayote, brugmansia (the infamous narcotic borrachero), some 250 varieties of heliconia , innumerable orchid varieties, and so on. That said, I wonder as to his alleged expertise in naming flowering plants, as I later am not able to cross-reference the Latin names of the plants using the Spanish names provided, or the names provided result in plants I have definitely not seen locally.

We park at the Estrecho, although I don’t descend, having been here two days before. Instead, I hang out with the grandson of the older man who made me juice two days ago. I chide him for being wasteful with the oranges he is juicing, which leaves him wincing slightly, as it probably reminds him too much of his grandfather. He is a lot more toned down and self-conscious, unusual for a particularly rural Colombian, but it could also be a commentary on his relationship with his grandfather. He does open up with his thoughts about oranges, how harvesting at different times of day, for example, changes their flavour.

Continuing on the final stretch back to San Agustín, the driver taps his fingers on the steering wheel to the rhythm of the classic salsa tracks playing on the car stereo. Colombian salsa is fairly indistinguishable from the Cuban variety, but as far as he is concerned, Colombians are better dancers. Cubans just don’t have what it takes, he adds, shaking his head.

He tells me that Cali is the country’s premiere salsa city, while most of the coast is dedicated to Vallenato. Cumbia falls into the realm of the Córdoba departamento …

I used to be enthralled with salsa but somehow it leaves me indifferent nowadays, which seems embarrassing. Moreover, I will only be a few days in Cali, and that trying to see the city and keeping my blog up-up-date, not going to salsa clubs all night. I don’t have the stamina anymore, and then my paranoid side is also telling me not to take undue risks in a Colombian city. After all, Cali is a city to think about security. I ask him what areas of Cali are safe, somehow a subject he doesn’t want to discuss. I have a feeling he doesn’t like me, probably because I ask too many questions and am too opinionated! In any case, I will have to do some thinking as to how I will be spending the few days I have in Cali.

The guide continues on another point, expressing discontent at the people of the Caribbean coast, who are very materialistic and try to take advantage of visitors with every opportunity. The rest of the country certainly is not like that! In any case, I am not going anywhere near the coast …

In Obando, the rest of the group enters the museum, while I follow the guide along the periphery of the parque to a small storefront, which opens into an entirely different world I could barely have imagined in Obando. Inside, the front room is very dark, but I can make out very heavy wooden furniture, some with high carved backs. Along the outside wall, small gourds hang in rows, some pots of orchids stand on the counter top, on the walls, framed prints and paintings, and unusual objects hang from the ceiling, including what looks like a witch’s hat, woven in the style of Colombian straw sombrero. The guide had told me that this place offers a fermented sugar cane juice that is popular with locals, but after one sip of the substance, I have to pass, as it tastes like apple cider vinegar.

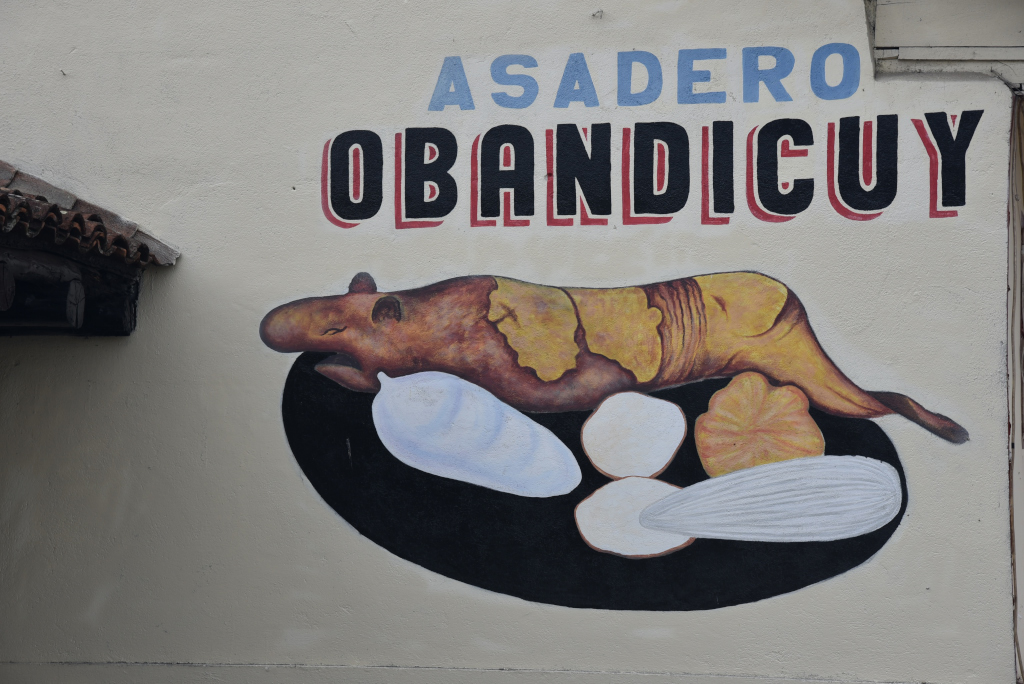

Following the sun shining in the back, another world opens up, the orchid-lined garden set up with tables for the comfortable enjoyment of the establishment’s specialty, the cuy guinea pig normally eaten in the south of Colombia. At the back is a small house set up with large trays hosting numerous baby cuy, feeding on grasses or sugar cane, waiting to be fattened for the purpose of ending up on someone’s dinner plate. At the back, a group of visitors from Ecuador are busy with a game of tejo. The sun beams down on the garden through the wild array exotic plants and orchids erected at wild angles around and above.

Back in San Agustín, I had thought about staying in town and enjoying a more adventurous dining experience, and for that matter, perhaps even visiting the ramshackle gym near the Parque Santander. But it doesn’t take long to convince myself that I will be much better off returning immediately to the hotel – and staying there for the evening.

I can’t wait to get back into the upstairs restaurant to take in the wonderful coffee the hotel offers. The ever-gracious employee deals with my raving and ranting in the most diplomatic manner, offering me the rest of the coffee from the specially prepared pot. I marvel at the uniqueness of the coffee blends I have tasted here, but as he points out, the flavour of coffee will vary according to the soil it is grown, how long it has been roasted, what plants it has grown alongside, and most importantly, the type of bean and the elevation it has been grown at. The coffee at the Hotel Huaka-yo is strong, intense, and has a distinct citric acidity, which makes me wonder as to whether it was grown in an orange grove, or close to an orange grove.

I re-emerge from my cocoon, the reality sinking in that if I wait too long, I risk missing the cutoff time for food. Preparing valiantly for a prolongued session outside the protection of my enclosed room, I drench myself with bug spray, which turns out to be another brilliantly inappropriate decision. My shorts are now stained in a way that is probably not reparable, thanks to the toxic slime covering my skin, and it’s not as if my remaining clothing makes me look much more presentable. Everything I touch is covered in this substance that refuses to dry or dissipate. So: cover yourself in toxic slime or risk getting malaria, dengue fever or Zika … And the stench of this stuff is hardly going to whet my appetite, either!

The staff is exceedingly polite, but I think I pushed things too far when I told them that Colombian food was largely inedible, and that the cook in particular still made me a pizza yesterday evening that was flavourless even after I begged the waiter to add as much garlic as possible. Actually, it is true, and the food is largely flavourless, and the people really have little sense of how to prepare food, and someone just has to tell them ….