February 25th, 2015

The sprawl of tables emanating over the Eden hotel terrace is populated either by older, self-contented police and military types, or younger, prepossessing men. The waiters are agile, attentive, and on top of their game. Erik, the retired journalist from Oslo who I met yesterday upon arrival, is already present when I emerge from my cocoon. He struggles with my inflected English, which of course I can desist from, but don’t, being such a rabid colonialist.

He prefers to be traveling in the smaller towns, avoiding the large cities. Erik hasn’t traveled much until the last few years of his retirement, and is now thinking of heading to Thailand, which he really knows little about. I warn him that the coast of the country will be a veritable zoo. He also uses a Tripadvisor as a resource. I encourage him to contribute information back to the resource, since all reasonably objective contributions, especially for more off-beat places, are incredibly valuable.

We order coffees, which are at least black, Turkish-style, made from powder, with grounds at the bottom, much better than anything one would normally expect here. However weak the coffee may be, it is still better than the alternatives. Then the soup I have for breakfast is made of greens and deep-fried bean curd, prepared in a flavourful broth, and accompanied by pickled greens and bamboo shots, also incredibly tasty.

In the hotel, the internet finally comes on, but is glacially slow. As I wait, I speak with the young attendant clad in a football jersey. He is studying medicine in Mandalay, and is originally from a small town near here, now seemingly well-ensconced in the somewhat urban lifestyle Katha has to offer.

I see many buses on the streets, ancient and decrepit for the most part, but nonetheless my understanding is that foreign tourists are not allowed to take them.

I run into the young Belgian-German couple I saw arrive at the Ayerwaddy hotel yesterday, where I met my Chinese and Norwegian friends. They are beginning their Myanmar trip in the Irrawaddy area, and seeing their time being sucked down the drain by the vagaries of government boat scheduling. The boat was to have left at 1 pm, but now the boat is supposed to arrive at 6 pm and leave again at 7 tomorrow morning, then take three days and two nights to complete the journey south. This just seems like such a profligate waste of time.

The price may only be $9, but the trip seems incredibly long, the allure of watching people on the ship and seeing the vendors approaching the boats with all manner of food items already something I have been taking in ad nauseam.

If I can get on the longboat tomorrow very early, I will take it to Kyaungmyaung, then take the bus to Shwebo, probably the next morning, a more efficient use of my time. And if I can’t get on the long boat, I will opt for the train to Shwebo, although that’s really an option of last resort, given my experience traveling north by train.

Further from the town centre – if there even is such a thing in Katha – the road emanating from the intersection the Eden Hotel is situated on gracefully evolves into a leafy country lane, flanked with rambling bungalows, consumed by a tropical fecundity, and on one side, the terse walls extending into the distance harboring the grounds of an expansive Buddhist temple.

Beyond the mosaic of humble women perched throughout the neighboring pavilion, the young monks remain indifferent, and then momentarily glaring resentfully as I point my camera at them, glued to their cell phones. Another monk disdainfully tosses the maroon tunic over his torso, seated behind his companion speeding from the confines of the monastic compound on the back of a motorcycle.

A possible remnant of the British rule, a tennis court, bordering on more overgrown plots, a consummate sprawl of weed-infested green, disintegrating wooden bungalows, and ancient vehicles, the likes of which would rarely be seen outside the country.

Swathed in subdued yet seductive fabric, conical bamboo hats arced deep over the dark faces, the all-female road crew remains unperturbed, responding with bashful ebullience to the faltering attempts at fragmentary greetings and the bridging of an insurmountable language gulf, their thanaka-braised cheeks spread wide with irrepressible smiles.

Another cast of exuberant women, stunning Burmese countenances perched at the back of a truck amidst a bounty of rose-coloured paper fans. Cyclists glide along the country lane, the children radiant, a confluence of the archaic and elusive modernity, an old complaint in this distant land, and certainly fecund territory for Eric Arthur Blair, whose stay in Katha was pivotal in the emerging dystopia of his fiction. The crumbling buildings that Blair – better known as George Orwell – inhabited, and whose backdrop inspired the setting for “Burmese Days”, are still there, sheltered by the dense tropical foliage from the outside world.

The river provides perfect photographic subject matter. Even from my position on shore, I can see the two people fishing from their canoe in the channel running between the shore and the vast sandbank, mirrored perfectly in the water next to them. Towards the neighboring village, women rhythmically slap their day’s wash against the river’s placid surface, and beyond, the disarray of mouldering boats, languishing in the season’s torpor, the broad somnolent river basin sprawling before us.

The low mountains against which Katha is situated are only visible to a small extent along the ledge overlooking the shallow river basin. The side of the road is lined with a channel of rocks. Judging from the view of work in progress below, the rocks will be used to build a retaining wall below. A sign has been erected regarding the protection of the Irrawaddy dolphins, although I am not sure how much impact such signage may have on anyone hereabouts.

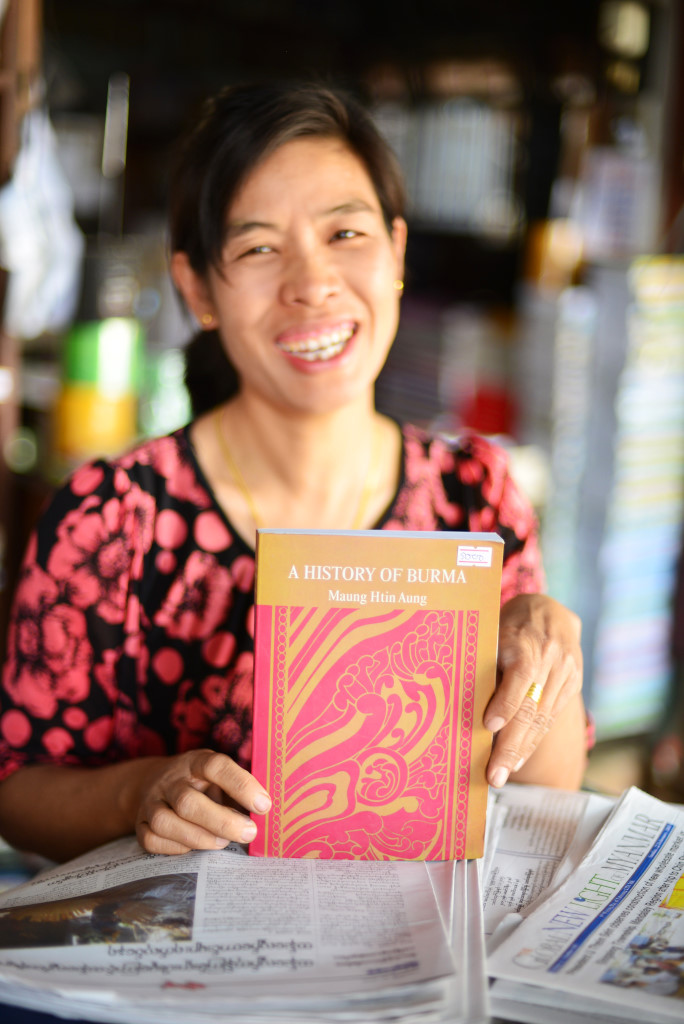

The burden of the country’s troubled history weighs heavily on the inchoate stacks of tomes devoted to the history, culture and literature of the country, the number of English-language works a testimony to the number of visitors seeking out the ghost of their English literary hero. Evanescent pastels wash over the riverfront facades, the extensively potholed tarmac leading to the road work I encountered upon arrival.

The decaying barges anchored on the shoreline bear solitary witness, the expansive banks of the river sprouting green, the sprawling grasses defiant in the face of the late season’s drought. The people wait at the river’s edge, for the boats to arrive, for the boats to depart, the rains to finally return and vanquish their thirst, the receding waters and exposed gills of the once mighty Irrawaddy to be again returned to its majesty.

And back into town, the two-storied dwellings huddle behind blanched awnings, shuttered windows peering over the ochre leaf litter and ancient trucks, transporting errant merchandise in and out of the paltry town core. Modest merchandise proffered in glass vitrines, wooden racks, hastily erected tables, and blocks signage painted with tendrils of liquid calligraphy. Vendors wait, patiently, their world slow, docile, bereft of misplaced hope.

The Buddhist temple situated where the road running along the river bank west of the jetty arcs landward could have been more interesting if its entire resident dog pack didn’t go berserk upon my arrival. The entire group of monks at the monastery is stripped down to the waist, busily hacking away at a tree stump, attempting to lodge it from its cavity. Another group work on the construction of a new monastery building. I am not sure of the impression it makes to be chasing the dogs at the monastery with wooden poles with the evident desire to hit them, although finally one monk wanders in the direction of the bulk of the canines with a rock. Why is it that you tolerate such aggressive animals on your property to begin with?

A serious-looking monk assures me that I cannot take photos of his kin, which I theorize is because they should not appear to be working, probably for similar reasons they are not to be seen playing sports, riding motorbikes or using cell phones – and yet they do.

The monastery building looks very posh, each floor quite high, portals separated by elaborately-shaped spandrels, the monks apparently having worked for a number of years to create this building. He speaks a reasonable school English, but doesn’t quite understand everything I say, not that he should understand my rambling. The reaction I get from the monks is worth the visit itself, ranging between indifference, astonishment, amazement, curiosity, and warm hospitality.

Back outside the hostile canine environment, next to the wall containing the temple complex, lies a series of watermelon vendors seated next to heaving piles of the heavy green-rinded fruit, one selling the entire chunk of one fruit for 500 kyat, offering a perfect means of rehydrating. Hilariously, I see a pair of fake Oakey sunglasses on her vitrine, a carbon copy of my own pair. She jokes we should trade, her neighbors laughing.

Small children greet me as I walk past the modest retail outlets and automotive workshops, the grown men serious and indifferent, women almost universally blushing and shyly greeting me. It is such an egocentric experience to meet so many beautiful women who really seem to be quite taken by me. I wonder how they would react when someone who is actually good-looking appears!

I churn out the “mingalabas” and “hellos” automatically, just randomly waving in the direction of voices I hear, although often I can’t place the person calling.

The Eden cafe is absolutely packed when I return. Erik is seated at one table at the back with his Chinese friend from Shanghai. An amusing conversation ensues, his heavily-intoned laborious English set against the jagged but enthusiastic English of his friend. And yet, the adjoining tables listen intently to our conversation. The Chinese man is actually floating between jobs, in a somewhat directionless state, and just seems to continue traveling. He has seen a lot of Asia, and has a wildly naive and optimistic flare somehow very East Asian: the new generation of independent traveler. Erik, on the other hand, should be a very conservative type, but he is so out of his element that he somehow fits in perfectly.

The Chinese man is still trying to figure out what his exact itinerary heading north will be, as well as how he will return to Mandalay from Bhamo. Erik is intent on catching the small local train from here to the adjoining town, which then feeds into Naba, located on the main train line between Mandalay and Mityina, not a stretch I want to redo frankly.

Erik’s friend shows us his photos from the day, having visited various sites in Katha. There is apparently some Taoist temple near the Buddhist temple along the waterfront to the east of the jetty that he visited in his journeys today.

The tables are mostly full of young hipsters drinking tea and coffee. The receptionist at the hotel later tells me that they come here to drink coffee, while the beer stations in the area are dedicated to drinking alcohol. Then again, very few people here can afford to just hang out and spend money in such establishments.

The menu at the Eden restaurant is a bit random. Due to the perennial challenges of language, it may not be the worst thing in the world to simply enter the kitchen and point, not that locals would in the remotest be resentful of this kind of behavior. I piece together a soup, the tamarind-leaf salad, and a sweet naan, although I really wanted the one with the curry. But my choices turn out to be quite amazing as well.