April 6, 2018

I wake up, disheveled and frankly starving. The restaurants in the area of my hotel and expensive and not really what I would want to indulge in for a solid meal, and while the street food could in theory serve that purpose, I am not always motivated to ingest that kind of fare, even if Cali seems to be doing a somewhat better job than elsewhere.

The bakery on Calle 2, just north of where I am staying, is not somewhere I had thought of stopping off for a snack, but it turns out that the empanadas, bunuelos, croissants with ham and cheese and pretty much everything else is coming out of the oven now, and is utterly remarkable. So, this is what Colombian pastries are like when they are fresh. Throwing caution to the wind, I ingest one after the other, until I am utterly bloated. And then to the Morus Express for breakfast …

Now that the sun is finally out again, I can take a few more decent photos of the small acts of whimsy that characterized San Antonio. Of course, that inevitably results in being stopped and told that I will get held up, mugged, shot, my camera stolen, etc.

The streets as anywhere else yield mysteries of form and colour, one colour offsetting the other, planters with bright plants set against a drab wall, an embellished balcony elsewhere, a road weaving between two unusual buildings, or a spray of bright bougainvillea splayed out over an arresting mural. The roads emanating from the north side of the hill the Iglesia de San Antonio is located on are rich in character, particularly given the steep escarpment laden with brilliant flowers they are offset by.

In the continuing saga of discovering places in San Antonio that are suddenly open, I find the Zahavi bakery and cafe, just around the corner from my hotel. Now is it open or not? The gate is closed, and yet I was just told by a woman a block away that it is definitely open – and she also insisted that I watch every move I make here, carrying my camera around, for the purpose of shooting all those incredible urban landscapes.

I pull open the gate – and indeed it is open. The establishment is divided into a bakery, retail space, and two seating areas, a wall with entrance and window separating the seating areas, the secondary one somewhat torpid and dark, but adorned with a lavish spray of flowers set in an alcove, the primary space far more sunny and inviting, but yet also exposed.

The coffee served here is excellent, although I will forgo any of the baked goods, as I just ate something like 8 rolls. When I find out that the owner is Israeli, I am curious as to whether his baked goods reflect any cultural inflections. At first he deflects, but then it turns out that the baked goods definitely do, and are excellent to boot. There are bisotti made with tropical fruit, cookies with cardamom and other spices, a traditional Jewish cheesecake, a flourless chocolate cake, and small rolls stuffed with chocolate and hazelnut. So I will have to be back, tomorrow, or on some theoretical future visit!

I ask him why the doors closed on all establishments here? For security reasons, he tells me, universal in Colombia. No, this is not a standard in Colombia, it’s only something I have seen in Cali. And so how are you supposed to know a place is open? He shrugs. Cali is dangerous, although it’s largely violence between gangs. But incidental robbery with violent overtones is frequent as well, and you do need to take peoples’ advice seriously.

Four people a day have been killed here in the recent past, and the violence has been escalating. Robbery is incidental and can happen anywhere, whereby people grab things from motorbikes. Just last week a tourist in the area was shot when his cell phone was grabbed, so this is not some distant, imaginary concept.

The low-level crime is performed by the foot soldiers of the gangs that run the country’s drug trade. Uribe at least made some inroads in combating the massive crime here, which is why things have improved so much here overall. The upper echelons of the gangs no longer flagrantly display their wealth. Humorously, the lower echelon criminals are reputed to drive Kias. Regarding Uribe – he is popular because he was a man of the people, simple, tough, humble, and didn’t run off to Europe when the opportunity arose. He eats corn and beans like the simple Colombians, and mingles with the people, rather than avoiding them at all cost.

I had passed by the imposing modern building housing the La Tertulia museum when I went to the zoo yesterday, and was curious as to what secrets the museum could contain. It is somewhat problematic to even find out where to buy a ticket, and judging by the confusion that arises when I attempt to do so, it seems that this is not something that occurs frequently, and I am about to find out why.

There is little to see on the three floors of exhibition space. It seems that the entire gallery is devoted to some exhibition that took place in the 60s that was intended to present Cali to the world. A city such as Cali would not have experienced linear growth forward, given the political upheavals, violence, and impacts of the drug trade that affected the entire country, particularly places like Cali. Colombians may seem to be both very happy and having their feet on the ground, but they have been through a lot.

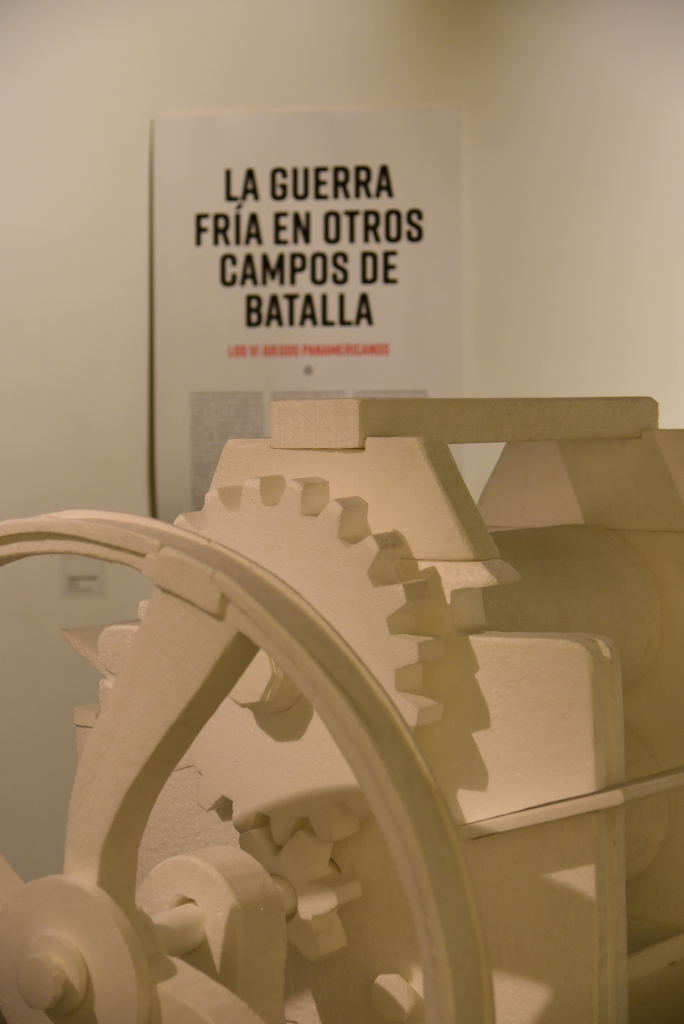

Much of what is on display has a documentary quality, supplemented by paintings and sculptural works, little of which seems of any import. As previously noted, the work derives from western concepts and aesthetics of the period, and not particularly well at that. However, the playfulness and provocation around the subject of the historical event and its significance in retrospect certainly is well executed.

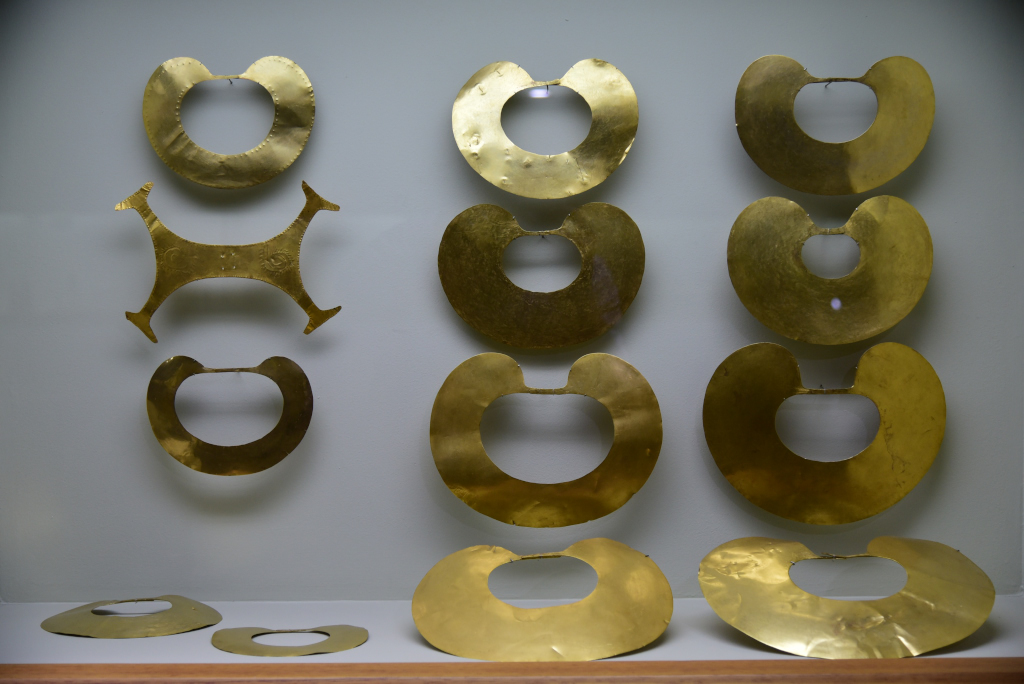

The Museo de Oro is just across from the archaeological museum, and despite being small, houses an important insight into the pre-Colombian cultures centred on Calima in the state of Valle de Cauca. The following information is taken from the pamphlet provided by the museum.

The cultures in the area of Calima lived in distinct epochs, including the Yotoco, Malagana, and Sonso. Early periods of this region were characterized by a rudimentary technology, absence of ceramics, and the use of wood, gourd and bone to construct containers, using instruments made of stone. Around 1500 AD organized settlements emerged in the jungle. These groups created relatively sophisticated ceramics. These cultures grew corn, squash, beans, rice and palms.

The society was hierarchical in nature, the most privileged presumably endowed with elaborate funerals, from which relatively sumptuous objects remains. The ceramics of this epoch focused on nudes adorned with collars, bracelets, women with large heads and men with body paint. Animals with features of serpents, cats, and bats are also evident in ceramic form.

In the first centuries A.D., a change was observed in the materials used, indicating the presence of a new culture in the region. The culture known as Yatoco extended into the eastern cordillera and middle valley of the Cauca river, where abundant tombs of caciques were found, replete with gold, ceramics and stones. The increasing agriculture was accommodated by reshaping the land, artificial ridges built to organize cultivation and accommodate runoff.

Among the ornaments used by the caciques and governors were porporos, small receptacles in which ground lime was stored for the purpose of chewing with coca leaves. The sacred coca plant was used with dances and rituals and during long days of work, for the purpose of mitigating exhaustion.

In the area of what is now Palmira, rich cemeteries were found with funerary trousseaux identified by unique pieces. The Malagana culture flourished here in the years between 200 B.C. and 200 A.D.; the Malagana golds work was outstanding, skilled workmanship and scale being evident in the objects found made of gold, including masks and diadems. The poporos with animal motifs also indicate that coca was important here.

Between 700 and 900, new groups appeared in the region, and built villages overtop earlier ones. The Sonso were more widely distributed than prior cultures, but despite the apparent larger presence, the culture was characterized by less opulence, as demonstrated in the funerary remains. The gold work was limited to casting, rather than hammering and further refinement. Pottery was also less nuanced, and more standardized in form.

The Spaniards arrived in the early 16th century, and over the next century the native cultures were largely vanquished, although traces of native blood are evident throughout the country.

Adjacent the primary exhibition of the Museo del Oro is a secondary exhibition which describes what is commonly known as the Kuna culture of southeastern Panama/northwestern Colombia. The bulk of the communities are located in Panama, the Colombian communities are limited to the Ibgigundiwala and Maggilagundiwala. The following narrative is taken from the placards of the exhibit.

“Our peoples’ name is Gunadule. Kuna, Cuna and Tule are incorrect, albeit very well-known, ways of writing our name. It is important to change the way our name is written, because from words it should be possible to perceive the smell of what we are.

Due to its geographical location, Darien, where these people live, has always bee an area of immigration and cultural exchanges. The Coclé pottery (800 to 1200 AD) found in the Gunadules’ ancient territory points to strong iconographic relationships between molas and pre-Hispanic indigenous aesthetics.

Galus are sacred sites located in layers of the universe where no people live. Only neles can visit them, because they travel through these layers in their dreams.

They are complex, fantastic architectural works, a mixture of shopping centres, churches and boats. They are made of gold of different colours, and flags are raised on their domes.

The malas that we women wear on our blouses imitate the structure of the universe. For the Gunadules, the universe is like a marrow with a series of superimposed layers inside it. Those layers that support it are made of gold, each one of a different colour: blue, red or yellow. Everything that is on them is made of gold and they are covered with many types of flowers. We Gunadules live in the top layer.

The Gunadules have had molas since the beginning of time. Their designs and the techniques for making them were kept in galus, sacred places that exist in various layers of the universe. Many of the Gunadules’ spiritual leaders, the neles, attempted to travel to the galus, but the scissors specialists, very beautiful women who protected them, refused to let them in.

Only Nagegiryai, a female nele, was allowed in. She traveled first to SabbiMolandalagalle galu, where she saw designs that changed like clouds in the sky. Time and time again she went back and forth, to teach the painting she saw on the trees and on the bodies of the young women. On another journey, she reached Dugbis galu, where she learned about the writing on the molas.

Seated on her hammock and combing her long, smooth hair, Nagegiryai used her chants to teach Gunadule women this writing.

In the course of their spiritual and therapeutic work, our neles risk their health and even their own lives, because they come up against powers that inhabit other layers of the universe. When they set out on their journeys, they are always protected by their guardian nussugana army of protective entities and medicinal assistants that inhabit wood carvings.

The nussugana are kept together, tightly packed in wooden boxes, awaiting the call from the nele. They live alongside crucifixes and superheroes from other cosmovisions, and these are accepted as protective elements.

Gunadule wise men differentiate, principally between two major design groups amid the vast variety of molas: naga molas, which protect and consist of designs that make elements of nature abstract, giving them a geometric shape, and goaniggadi molas, where the designs are figurative and depict activities and surroundings of everyday life.

Protection molas have a vibratory quality that nauseates, confuses and distracts an enemy who is threatening women.

The designs on protection molas are a type of Gunadule writing. Each design has its own name, together with a chant associated with physical and spiritual care practices.

There are four styles of drawing on protection molas: arrows facing inwards and outwards, connected spirals, diagonal turns, and independent modules.

The naga mola protects Gunadule wome, the source of fertility and safekeeper of tradition. It averts dangers that threaten her, from sickness and evil spirits to abduction and rape. By wearing the mola on her blouse, she merges into Mother Earth, covered by the trees, flowers, leaves and soil that are her own mola.

The 1925 Dule revolution on Panama’s Comarca Guna Yala islannds was one of the greatest moments in Gunadule history. This uprising has marked relations between the state of Panama and the indigenous government for ever. Its legacy gradually led to political and cultural autonomy being declared in Gunayala, the land of the Gunas.

The women in our community hold two celebrations, which can be several months and even years apart. During this time, we learn traditional knowledge for participating in family and social life from women around us. After the second celebration, possible suitors can approach us.

The first celebration is held during the menarche. The men build a special enclosure in the girl’s house with leaves obtained from Heliconia or from bitter palm, and she has to stay inside this. The women bathe her continuously with water, quartzes and medicinal plants, to protect her from the bonimalas. Before leaving, they give her the blouse with the protection mola for the first time, winis for her calves, the painted skirt and the red shawl for her head.

In the second celebration, the girl and her family pass from intimate withdrawal to the public festivities. The young girl together with the men and women who took part in the first ritual, and have a big party. Guided by the wise men, who know the chants and how to prepare chicha, they celebrate the arrival of a new woman in our society.

I had wanted to cap off the day with a stroll through the upper reaches of Barrio Granada, what with its posh restaurants, cafes, bars and leafy setting on the north side of the river. I don’t quite want to sit down anywhere and spend money, largely because I am not that hungry and have other plans for the evening, but nonetheless, this is hardly the worst area to be strolling through. At the intersection of Avenida 9 and Calle 13, I look into the windows of Saheima Joyas, a store dedicated to creating pieces of jewelry using brass and semi-precious stones, along the lines of the work I bought in Popayán, but with cleaner, more classic lines.

Upon closer inspection, I find the work astonishing, featuring clean lines, alluring contrasts between translucence and reflectance, polished and rough, bright and muted, incongruous juxtapositions of materials, balance vs. imbalance. A necklace with cultured strands of white pearls culminate with strands of black pearls. A necklace with pale blue polished veined beads onto which a sequence of slices of the same stone are hung, the edges unfinished, alternating with bright orange coral strands.

A necklace with pale blue polished stones features two bright orange stones further toward the bottom, onto which veined blue oblongs are hung, upon closer inspection revealing complex cut patterns. A necklace with large red stones culminates with ivory cultured pearls alternating with embellished brass ornaments, and onto which a polished mother-of-pearl shell is hung. A necklace with large polished amber beads culminates with alternating polished amber and raw amber pieces. Earrings and rings are composed in the form of traditional jewelry using brass and Swarovski crystal, with precisely chiseled and polished crystal set in impeccable settings. And so on …

The poor owner has to listen to my effusive compliments, waxing on eloquently as to the beauty of her work, the degree of inspiration, ingenuity, etc. it reflects, but in the end, talk is cheap, as I don’t buy anything. The prices for the work are relatively innocuous, at the very most several hundred dollars, most relatively elaborate necklaces well under $150, and yet even so, local women are loath to spend that kind of money. I can’t comment on how viable her work is here, but I can only imagine that women in the larger world would love to get their hands on this kind of work. But what launching an online jewelry business catering to foreign markets would entail is also well beyond me …

One of my missions in coming to Cali was to visit some salsa clubs, hoping that there could be great live bands to take in. Well, tonight was that night, and after scrawling the addresses of a number of places in the immediate area – in fact, the immediate area is a salsa hot spot – I leave the hotel, hoping that I won’t make any unfortunate experiences, but the only really unfortunate experience is the bittersweet realization that this is not a place for me, a foreigner wandering alone into an environment firmly defined by the sensuous embrace of a man and a woman to the sound of the world’s sexiest music.

But if you are a foreigner on your own, what do you do? I am so not into playing the game, having to explain myself, in a confined space where I would rather just let loose and forget about everything. Once inside, what do I do: just stand there and watch? Make small talk without being able to even hear my own voice over the loud volume of the music? Without being able to understand what people are saying, or even care? Be constantly of guard for possible scams, not being able to leave my drink unattended for a moment, not trusting anyone’s intentions? And having seen the prices of booze here, pay ridiculous amounts of money for crappy drinks?

Sometimes traveling on your own sucks …

So: I walk by, peer into the opaque doors, hear the loud music reverberating through the walls, see the outlines of locals dancing to the sensuous rhythms, and then continue. And yet sadly, knowing how Colombians are, there would be no desire to make a person uncomfortable. But I just don’t have it in me – and in any case, I’m not missing out on live music.

Scattered figures mill around the entrances of the clubs, and around, street grills preparing arepas and sausages, the smoke tendrils drifting upwards in the halogen lights. A few brightly-lit eateries face the parque as well, largely bereft of clientele. Overall, these clubs don’t appear to be too busy on a Friday night, and with the reputation of going on for the better part of the night, perhaps the crowds show up later? Given how early I normally get up, it is already far past my bedtime, never mind staying here until 3 or 4 am.

Immensely fascinating is the street life here at midnight on a weekend. It certainly is nothing that I expected here. The backdrop is the typical low key urban residential environment that looks like some decrepit setting of a noir movie, but in reality is a canonical environment in urban Colombia. Parque Alameda has a very homely feel to it, and while salsa music is emanating loudly from a handful of clubs on the square, the place has a relaxed, unpretentious, almost carnival-like feeling to it. It’s not as if salsa music isn’t ubiquitous here anyway.

Cali certainly does not feel tropical at all in this landscape of dense housing and shuttered talleres, never mind the fact that it isn’t even hot. But there are unusual inflections, in terms of the lighting, the arrangement of the city blocks, the homely, modest eating establishments that crop up here and there, the loud bars whose long-haired clientele spills out onto the street. En route to the Parque Alameda, I pass by a group of long-haired, dour-looked, leather-jacketed youth listening intently to a Motorhead song on their boombox.

Certainly not what I would have expected. Most interesting is the busway and park belt woven into the merging of Calle 5 and Carrera 15, featuring plazas, green spaces, overhead walkways, fountains, and commemorative statues, taken over by young hipsters whose look is a far cry from the typically quite conventional look of young Colombians. At the far end, the Loma de la Cruz, where the daytime artisanry market is located.

I had intended of going to Buga tomorrow, but am now not sure, as I would love to wander through the neighborhoods adjoining Calle 5 and explore during the day. I had been uncertain about doing so for safety reasons, but if I feel comfortable walking around here at midnight, why would it be less safe during the day? And then I haven’t visited the Cristo Rey on the hilltop overlooking the city, either.