February 1st, 2018

I wake up and write for several hours. A heavy fog asphyxiates the city.

One of the major attractions in town is the Pozo de Donato, which is apparently located along the main road radiating to the north of the plaza with the Colegio Maldonado. The pozo is a pre-Colombian archaeological site of the Muisca people that populated the region prior to being vanquished by the Spanish.

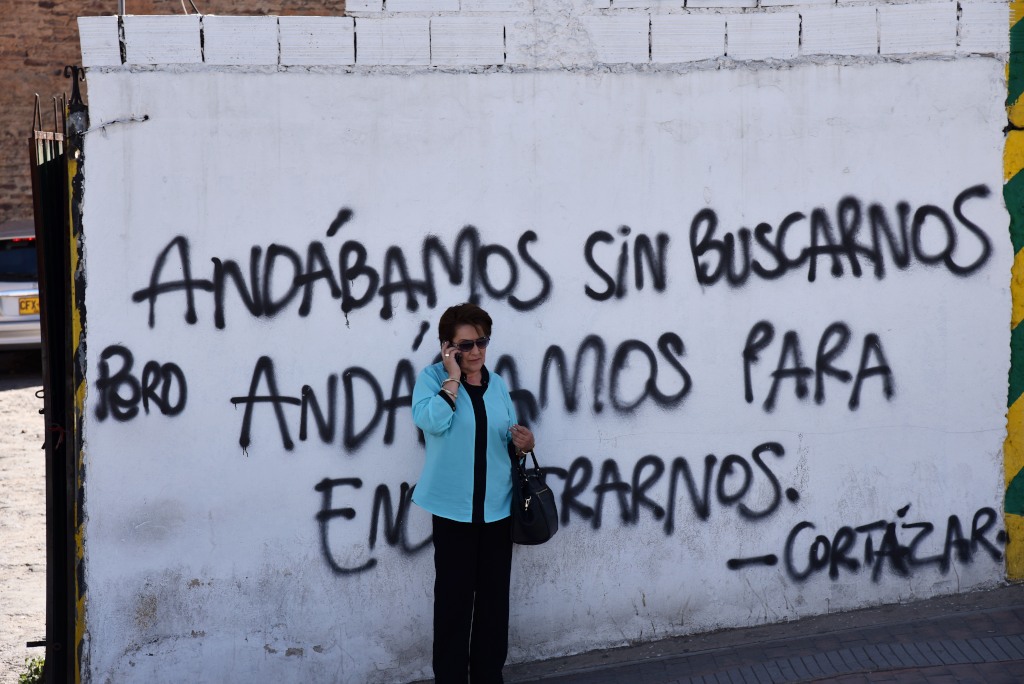

Making my way northwards, I see the triste buildings and urban artifacts consistently livened up with bright murals and graffiti. Some of the characteristic colonial structures are visible on the descent, although the feeling of the street becomes increasingly suburban.

The urban landscape becomes bland, more sterile, but then also more useful from a retail perspective, the stores larger, and with more selection. There are expansive restaurants, some quite posh, as well as car dealerships, and to a lesser extent, talleres. I pass by a very large fruit store – it would be wonderful to buy a nice selection of tropical fruit, except that it hardly gets so hot as to be motivated to eat copious amounts of fruit.

At some distance from town, much further than had been described to me, the pedestrian overpass that apparently leads to the pozo appears. The rail lines adjacent the newly painted train station are overgrown with grass, presumably long defunct. I join the lineup to sign up at gate across the street, but then it turns out that this is the university, not the pozo I am looking for.

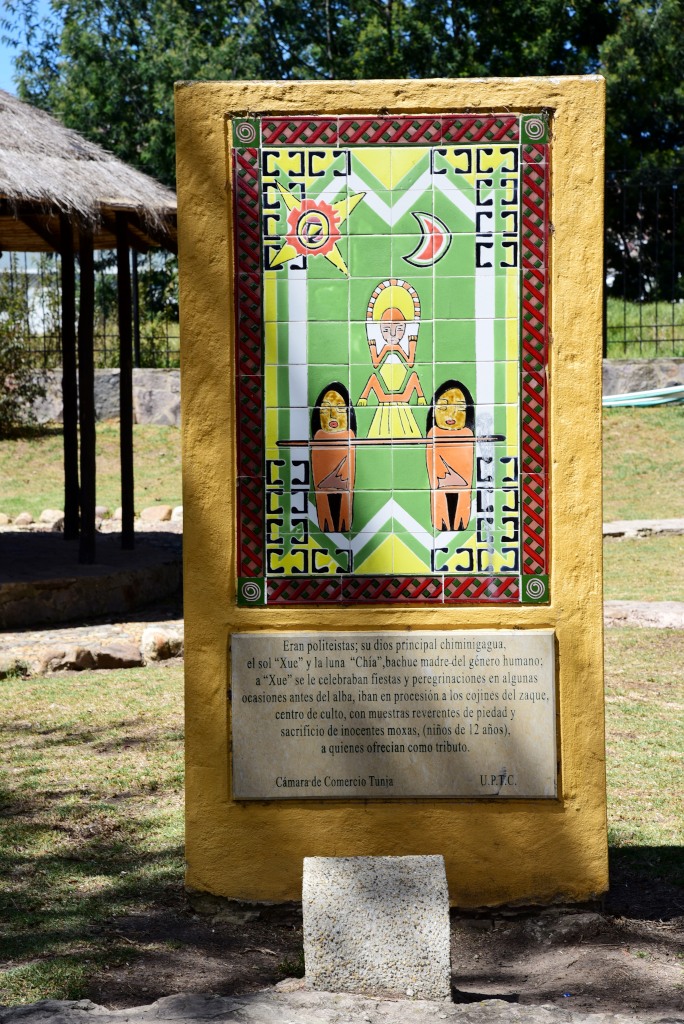

The Pozo de Donato lies further down the sun-bleached block, and consists of nothing more than a large rock-lined tank of water in a modest park setting, with a concession of some sort that is currently closed, with stelae lined along a walkway that describe the customs of the Muisca people that inhabited the region in the era prior to the arrival of the Spanish.

The well or pozo looks suspiciously new, given the impeccable rock and plaster work lining the opaque green water. A few people hang out the desultory benches that line the park as I slowly walk from stela to stela, skimming the information presented about the Muisca people, describing the type of housing they occupied, implements used, religious and moral customs, and social and legal traditions. The park does not represent the most memorable tourist artifact, but so goes the life of the tourist – it’s not all the Taj Mahal.

I return to the Hotel las Nieves II, but there is still no internet. I pack up my laptop, with the idea of finding some appropriate café that has wifi and electrical plugs on the west side of the Plaza Bolivar (or anywhere, for that matter), but am not successful. As I weave through the blocks radiating from the main square, all the cafés I seem to have spotted yesterday afternoon are suddenly not in evidence.

Calle 24 (that the Hotel as Nieves II is located on) mouths upon a charming park rising upwards towards the centre of Tunja, a few character buildings visible through the screen of trees on one side, a police dispatch at the top of the park, and a historic shuttered church looming over the park from the inner city side.

I climb the staircase at the back of the church towards town, and one block further arrive at the back of the Mercado Real, the brightly painted expansive structure that sits in the northwest corner of inner Tunja, impressive and regal, although a probably far too optimistic project for the likes of Tunja, given the kinds of establishments and street vendors the structure is ringed by. The few storefronts that are occupied in the building are of middling quality, and in no way reflect the grandeur the structure attempts to achieve.

Beyond the Mercado Real, the streets that appeared redolent in charm and history when I arrived now appear bland, tired, with errant street vendors, small, inconsequential shops, and aimless crowds. The frustration at not being able to have net access grows, reminding me of the year-long journey I took in 2010, in which I belatedly spent copious amounts of time trying to get internet access.

I do see cafés on my route, but no place that would be appropriate to set up my laptop and get down to business. That leaves La Casa, which should have wifi – and they do. I feel somewhat self-conscious setting up shop in such a trendy restaurant, but I am sure to order coffee and their lulo cheesecake in a jar, except at the end of my session it turns out I have nothing more than a COP $10,000 note in my pocket, having left my money belt in the hotel. How embarrassing!

I had originally intended on going directly to the bus station for the purpose of visiting the Puente de Boyacá, but now I need to go back to the hotel and pick up my money. I have precisely 50 pesos in my pocket, and that won’t be going too far here.

At the tourist office, I am regaled with detailed maps of every province in the country, with colour-coded icons used to tag attractions by type, which is very useful, although the maps do become somewhat crowded. However, the level of detail provided goes far beyond anything the Lonely Planet guide would provide. The maps will help clarify the remainder of my itinerary in Colombia, as well as set the foundation for further trips to Colombia, provided I don’t get stuck again in Canada for years on end with no break, as I did in the last few years.

Another funeral is gathering masses of black clad people into the cathedral, wreaths being unloaded from small cars. At least the woman who passed away had lived a long life and obviously has a huge family. At my funeral I’d probably get no more than a few stragglers. But then once you’re gone, you’re gone!

The traffic is congested on Carrera 9 in the approaching rush hour, the air asphyxiating with black exhaust fumes spewing from the microbuses’ artful choreography around parked cars and narrow turns. I have walked around much of the north side of the Plaza Bolívar, but surprisingly, not this street, even though it runs adjacent to my hotel. Through the thick smoke I make out character adobe buildings, whitewashed and amended with bright colours, with the obligatory terracotta roofs.

A bedraggled and graffiti-laden park attracts a few stragglers, including young chess-playing hipsters, in front of the San Augustino cloisters which was a bank, and is now a public library.

What a romantic setting for a public library!

At the hotel, I pick up my money belt, but still no internet. I drop off the laptop, and now am definitively heading to the Puente de Boyacá. The bus station is two steep blocks down the hill from the Plaza Bolívar. It would be hard to believe it is so close, but the hill drops off so steeply the station is simply not visible from the roads above.

The simple exterior facade of the Iglesia de Santo Domingo reveals a classic Churrigueresque interior. The altarpiece takes the shape of the massive multi-leveled gilt grid of coffered images of saints, set in against the wall of the apse, a similar altarpiece occupying the chapel at the rear of the left transept. A rich tapestry of medallions and rosettes lines the walls and ceiling of the lavish church.

The bus pulls out of the station, ambling down a main road heading south in Tunja, the exhaust fumes still quite pungent, the green hillsides dotted with houses rising up to the brilliant cumulous tufts above.

Our speed increases as we reach the highway, the air clearing, and the landscape becoming even more impressive. The road weaves along the sides of the verdant hills, a landscape of green slopes, cerulean skies and ceramic clouds unfolding around us. I doubt many of the passengers on the van are as appreciative of the romantic imagery as I am.

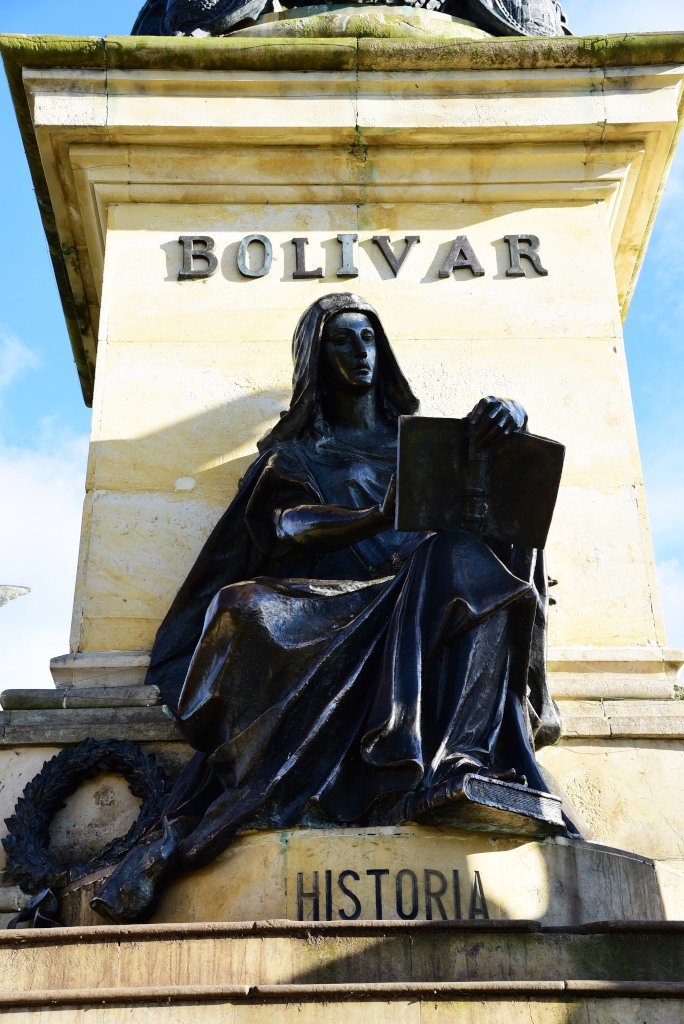

A dramatic 19th-century monument rises from the crest of a hill above the valley that the highway to Bogotá swoops through. It turns out that the Puente de Boyacá is the bridge we just crossed, where the battle of Boyacá was fought and in which the Spanish were vanquished by forces of independence, which effectively gave New Granada independence from Spain on August 7, 1819.

The German sculpture depicts five allegoric female figures (symbolic of Colombia, Venezuela, Peru, Ecuador and Bolivia) holding Simón Bolívar.

I climb up to the monument with a small group from Bogotá, who respond to my questions in a fairly dismissive fashion. In this case, the big city definitely does not beckon! Around the back of the monument, the walkway continues to a modern church built along the ridge closer to the highway, a long of arc of flags of the provinces of Colombia running back towards the entrance of the site.

Thinking about what the visitors from the capital told me, I ask a tout at the bus station as to the amount of time required to return to Bogotá from Tunja. Two hours? That’s all? That may be a good reason to return to return to Tunja once I have completed my travels in the area, and then Bogotá in order to continue to Medellin.

I am also thinking of possibly visiting the small tract of the Amazon somewhere in between, although I need much better internet access than I am getting now to plan my trip more effectively.

As an aside, I can’t believe how expensive gasoline is here. I thought the prices I was looking at were by gallon, but no, the COP $9,000-odd lowest price I see advertised at gas stations is for a liter. It seems unbelievable that so many people here should be driving cars to begin with!

I am later corrected in this matter, however – the price is per gallon, although still expensive for an underdeveloped, oil-producing country.

Passing by the square en route to the Plaza Bolívar at which I got my first taste as to the town’s character, I see a large gathering of people wearing green T-shirts and holding balloons of various shades of green. I am told that the Allianza Verde actually represents a single green party, and that despite being a leading contender for the Senate and Congressional seats here, will probably not win.

I am quickly introduced to a man fluent in English, with an agile intellect and somewhat flamboyant temperament, who regales me with information about the political realities of Colombia. It turns out that the Boyaca departamento is the only one in Colombia that has a green governor. What’s more, the governor comes from a humble background, and went to a public institution, unlike the dominant political class that exclusively attends the Jesuit-run privileged private schools.

A year or so ago an assassination attempt was staged which was allegedly intended to make his intended death look like an accident, but people are pointing fingers at the police. His political orientation is not welcome in conservative circles, and in fact, the attempt took place when he was attending a farmer’s strike.

Despite the attempt at coming to peace with insurgent groups, the very government of Colombia has subverted the peace accord with the FARC, and killings of activists in the country continues unabated. The FARC may have been neutralized, but there are still very sophisticated fringe insurgent groups, primarily from the far left, that operate with impunity.

On the political front, the entire spectrum of parties is represented in Colombia, from the extreme right, affiliated with paramilitary groups and deeply conservative elements of the Catholic church, through to liberal-right, left-liberal, Communist and extreme left-wing groups. Politics in this country is not for the faint-hearted. But yes, the Allianza Verde is a real force to be reckoned with in the country, even in the departamento of Boyacá, which is hardly some fundamentally progressive place.

He insists that I am not interrupting whatever he is doing at this gathering, although given the nature of what he tells me, he has too many irons in the fire to be too invested. More importantly, he wants to meet a friend, and he insists that I meet that friend as well.

A sandy-haired taller man in a corduroy jacket wanders across the top of the plaza, then descends to where we are located, greeting my friend and myself with a broad smile. He tells me he is vaguely politically aware, respects the process, but is nowhere the political animal that Jaime is. And yet Jaime appears himself to be a political chameleon as his wide-ranging rhetoric reveals over the course of the next few hours.

Our chatter continues, but the consensus is to sit down somewhere for a coffee. I would expect the two to have an inside scoop on just the right café, given the avalanche of establishments that are found here, but we end up in a smaller place tucked into one of the narrow passages that opens up somewhere on the block above leading to the Plaza Bolívar.

Jaime is an endless fountain of knowledge, rattling off events, dates, the names of historical figures, jumping from one topic to another often unrelated one, in another words a kindred spirit, and an utter gem. And not someone who I would ever imagine encountering in the streets of Tunja!

Jaime indicates that Boyacá enjoyed a greater degree of economic engagement relative to other departamentos in the country, as the church required landowners to divide their lands amongst their serfs, so as to maximize economic engagement of the people, minimize marginalization, optimize commitment to the crown and church, and minimize the ability of landowners to become too wealthy and hence represent a threat. To this day, most citizens of the province own their own small parcels of land, and there are no large-scale landowners.

As the lands of the savannah both to the north and southeast were broached much later (as they were considered undesirable frontier lands, too hot and fetid), they were subjected to violent conflicts between various interest groups, including settlers, guerillas, and pretty much every interest group that has emerged in the country seeking power and wealth, and which was also a catalyzing issue around La Violencia.

He gives me a rundown of the most important events in Colombian history, including:

• The assassination of Jorge Eliécer Gaitán in 1948, which set the stage for La Violencia

• La Violencia, the violence that erupted in Colombia in 1948, which set the stage for what has transpired in the country since

He claims that Robert McNamara, Fidel Castro and Che Guevara attended the fateful 9th International Conference of American States in Bogotá in 1948, although in reality, the U.S. Secretary of State that attended this meeting was George Marshall, and given that Guevara entered the University of Buenos Aires in 1948 to study medicine, he would definitely not have been attending said conference in Bogotá in any capacity. Castro traveled to Bogotá that year with a Cuban student group sponsored by President Juan Perón’s government, but would not have been in any capacity to attend the conference either.

Jaime recommends I read works by the following writers to understand more of the country’s history at the time of La Violencia:

• Germán Castro Caycedo

• Orlando Fals Borda

• Germán Guzmán Campos

It turns out that Jaime is quite the family man himself, having gone through a succession of wives, very much loving his current wife, who apparently comes from an old Jewish family just as he does. For three hundred years they have been serving the funerary needs of locals, by appointment of the Roman Catholic church. If I understand correctly, they were assigned this role, as it was considered unclean for Christians to work with dead bodies. She is presently the owner of the Floreria San Francisco, which I have probably passed a number of times to and from the Plaza Bolivar.

We finally leave the café, and then immediately run into a succession of other people who great him on the plaza. Is the town ever too small for this man, physically diminutive as he may be, but ceaseless in his energy and mental wanderings. Although it would seem that the director of El Tiempo Boyacá has other things to do than be engaged in superficial chatter with myself and Jaime, and the same would apply to his former employee.

With respect to the particular openness and quality of education that Columbians enjoy even in the public school system, Jaime tells me that the influence of England’s Jeremy Bentham and Germany’s progressive educational traditions had a tremendous impact on the country and the caliber of education Colombians have been privy to.

We climb the steps to the San Francisco church just as the door is closed for the night. We remain on the plaza in front of the church, his voice resonating across the plaza as he provides a synopsis of the sect’s history in Colombia. Colombia has some of the few Franciscan representations in Latin America, as they were against the aggrandization of the other orders, involving the exploitation of the indigenous people in the manner that was sanctioned and enabled by the Jesuits. Hence the Jesuits ensured that the Franciscans would assume a minimal presence – and even where they were allowed in Colombia, that their role would be limited.

The church was focused on garnering tributes to be able to develop and pay for serious artists, who were necessary to establish the prestige of the colony and the church in what at the time was one of the most important outposts of Nueva Granada.

Jaime’s wife was three months pregnant with someone else’s son, and yet he still married her. He had already left several other wives behind prior to marrying his current wife. He has five children, two his own and three adopted. The son his wife was carrying when he married her is now grown up and works for the U.S. military in some intelligence capacity, but is not at liberty to say what he does. He was stationed in Roswell, and is in Colorado Springs, obviously another reason leftists here wouldn’t like him.

Jaime points to the cartoon faces through the town that represent him. I have actually taken at least one photo of these cartoons. What a reputation he must have here! He was kidnapped some while ago, and when he disappeared, huge protests occurred on behalf of the student body. He was released again, but he tries remaining as conspicuous as possible in the city, due to the continuing likelihood of being targeted, particularly for his involvement in so many political or sensitive issues. In the warmer half of the year, he returns to the United States to pursue medical or teaching work at major institutions in the U.S., where he is also safer.

Jaime points to the Fiscalia offices as we walk down towards the street with my hotel: the Fiscalia saved his life, and they are the one agency that allows the country to maintain some degree of normalcy and legality, given that they represent the judicial arm of government that is not controlled by the police or army, which is very important in Colombia.

Even though I try to be as cost-conscious as possible when traveling, I decide to head to La Casa for dinner. The idea of blowing my budget so far out of the water should be a concern, except that it will reflect an amount that is a relative pittance back home.

I order the recommend sobrebarriga (flank steak) in salsa criolla, preceded by a crema de auyama (butternut squash) soup. The sobrebarriga is accompanied by a simple salad with an exquisite dressing in addition to white rice. The sobrebarriga includes two large portions of stringy and rich flank steak, prepared with potato halves in a criollo stew, which seems to be made of tomato, onion, corn flour, mustard, and saffron (or annatto), or something along those lines.

The dish should correspond to a Colombian standard, and is done to perfection. The waiter insists that the squash soup has no spicing other than salt, prepared in sous-vide fashion, but I don’t agree with him. But no matter: the soup is interesting in terms of flavour and texture, and is also very good.

Wood plaques with intriguing modern metal artwork adorn the walls of the space, while the bathrooms merit special attention, both men and women’s washrooms featuring a rear wall covered in tiles with colourful designs, reflected on the other wall in an enormous mirror framed in sculpted brass, water being piped through elaborately shaped industrial brass tubing into a brass basin.

Sadly, I am the only customer present this evening. I can’t even imagine how locals see this space, as it is fashionable far beyond anything I have seen in Tunja. I had not seen anything of the sort even in Bogotá, although it’s not as if I have really made a thorough attempt to explore the areas where more interesting restaurants in the city may lie.