September 12th, 2018

Located toward the centre of the 20th arrondissement in Paris, the Père Lachaise Cemetery is the largest cemetery in the city, and with more than 3.5 million visitors annually, the most visited necropolis in the world. Père Lachaise was the first garden cemetery in Paris and is also the site of three World War I memorials.

Père Lachaise is a major tourist attraction, renowned for its tombs of notable figures. The cemetery’s hilly terrain and tree-lined avenues are at once overcrowded, peaceful, and seductive. Sculptures abound, and the tombs run the gamut from simple, flat, horizontal headstones to elaborate mini-chapels open to the public. Some of the tombs are immaculately cared for, others dilapidated and abandoned. Maps showing the locations of the most popular grave sites are widely available.

Among the many famous people buried in Père Lachaise are Peter Abelard and Héloïse, Molière, Eugène Delacroix, Jacques-Louis David, Georges Bizet, Frédéric Chopin, Honoré de Balzac, Marcel Proust, Georges Seurat, Oscar Wilde, Sarah Bernhardt, Isadora Duncan, Gertrude Stein, Colette, Edith Piaf, Marcel Marceau, Richard Wright, Yves Montand, and Jim Morrison. The remains of Abelard and Héloïse (who died in 1142 and 1164, respectively) are reportedly the oldest identifiable bones in the cemetery.

The cemetery takes its name from the confessor to Louis XIV, Père François de la Chaise (1624–1709), who lived in the Jesuit house rebuilt during 1682 on the site of the chapel. The property is situated on the hillside from which the king watched skirmishes between the armies of the Condé and Turenne during the Fronde. It was established as a cemetery by Napoleon, who had declared during the Consulate that “Every citizen has the right to be buried regardless of race or religion”.

The French officials approved the transformation of 17 hectares of Mont-Louis into the Cemetery of the East in 1803. The neoclassical architect Alexandre-Theodore Brongniart used the English-style gardens as inspiration for the cemetery, incorporating uneven paths adorned with diverse trees and plants and lined with carved graves.

In its early days, Père Lachaise contained few graves, as it was considered to be situated too far from the city, and many Roman Catholics refused to place their graves in a cemetery that had not been blessed by the Church. A marketing strategy was devised to improve the cemetery’s stature, where in 1804, with great fanfare, the remains of Jean de La Fontaine and Molière were transfered to Père Lachaise, and subsequently the burials escalated considerably. By 1830, Père Lachaise contained more than 33,000 graves. Presently it holds more than 1 million bodies, and many more in the columbarium, which holds the remains of those who had requested cremation.

A columbarium and a crematorium was designed in a Byzantine Revival style in 1894 by Jean-Camille Formigé, and was the first built in France. The roof consists of a large brick and sandstone dome, three small domes and two chimneys. In the 1920s, the main dome was decorated with stained glass windows by Carl Maumejean. The final columbarium is composed of four levels: two in the basement and two exterior levels, both can contain more than 40,800 cases.

The Jewish enclosure in Père Lachaise opened on February 18, 1810, and expanded later on in the 19th century. Enclosed by a wall, this part of the cemetery included a purification room and a pavilion for the caretaker. In 1856, a Muslim enclosure was opened as well as a mosque, including a waiting room, a lavatorium intended for the purification of Muslims, and a counter for religious effects. The Muslim enclosure became the first Muslim cemetery in France.

Immediately to the south of Père Lachaise lies the charming village of Charonne, centering on the Saint Germain de Charonne church, dating to at least the 12th century. Directly opposite is the ancient village high street, the still-cobbled rue Saint Blaise, lending the area a quaint, provincial atmosphere. For most of its existence, Charonne was a quiet and bucolic place, where wealthy Parisians had country houses.

Unlike other original communities that were absorbed into Paris at the same time, such as Montmartre, Vaugirard and Batignolles, Charonne is still authentic, and hasn’t sold its soul to gentrification. It is not a village of luxury food stores and antique shops, but rather a place that provides a home to those excluded from the city centre. Despite the area’s seeming scruffiness, you can see groups of children playing and locals gathered at modest cafes. The back alleys of the neighborhood are pedestrian-friendly. The area does hold surprises, including the old Petite Ceinture railway line, which appears overhead near the busy rue des Pyrenées.

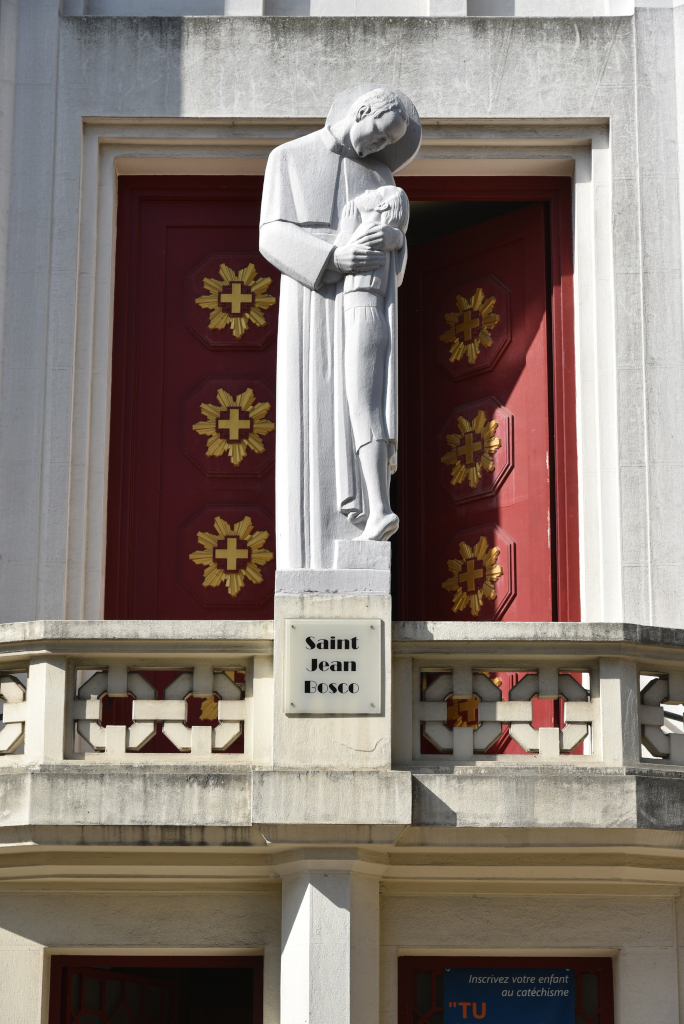

The place de la Réunion acts as the village square, recently renovated to include miniature gardens with wild grasses and even a small stream. Picnic tables have been installed, offering views across what remains a roundabout bordered by concrete. The nearby rue Alexandre Dumas offers another surprise – perhaps the city’s best preserved art deco monument, the Saint Jean Bosco church. Although built 60 years after Charonne was absorbed into Paris, it was still designed with the local community in mind.

(Narrative excerpted from Wikipedia, www.britannica.com and The Guardian)