February 19, 2018

Today is the big day on which we hike the Sendero Ritacubas, the trail leading to the highest peak in the Parque Nacional Natural El Cocuy, with an altitude of about 5,000 metres, and lying on the north side of the park. Let’s see how I make out. The day does not begin well, given that we have to wake up at 4:45 am, and I barely slept at all, gasping for air during the night due to lack of oxygen at this elevation, not a good indication as to how well I will be dealing with the rapidly increasing elevation as the hike progresses.

David and I clamber over each other to get ready in the tiny, sparse room, not a pleasant feeling, never mind this early in the morning. Breakfast is consistent with the dinner we had yesterday night, flavourless caldo de costilla, bland scrambled eggs, and cheese that tastes like cardboard. David is decided: no supper tonight for him. Meanwhile, Kim has a sinus infection or cold, and is definitely not going on the hike. In retrospect, given how difficult the hike turns out to be, I may have been better off not going as well, although in the end the hike will have offered spectacular views of the high sierra of Cocuy.

I dread the idea of doing anything this early in the morning, never mind climbing up a mountain at this elevation in sub-zero temperatures. Oh well, once I have survived these hikes I can move on – to the almost universally polluted and loud Colombian cities! At least David is low-maintenance, and John a very kind, laid-back American, and a genuine pleasure to be around. We drive towards the park office, where the guide Jorge meets us, and no, he did not ride up from El Cocuy in the middle of the night because he lives close by, then on to the dumpy cabañas we had actually considered staying in yesterday.

And we are off! Trudging through the darkness, the ridges on either side of the valley rising ominously above us in the pre-dawn darkness, their height giving little idea as to the enormous elevation we will be gaining during the day. At a lower elevation, the valley we have come from is still visible below us as well as the dramatic ridges of the low mountains that define the landscape of Boyacá. The motive for starting so early is to assure that the sky remains sunny for the entire hike; soon we see the massive rock ridges around us illuminated in the first rays of glorious sunshine. We climb through the fields of freilejones still bathed in darkness, then weave higher and higher towards the illuminated ridge above us. Gasping for air, I have to stop continuously to keep my lungs from seizing up. Suddenly the freilejones and rock ledges around us are bathed in the full light of dawn …

I walk slowly, finding it difficult to maintain the pace of the others, and as the pitch of the trail becomes steeper, I have to stop at increasing intervals. My lungs are heaving, seized up in pain, and only stopping, relaxing, sitting or lying down, and breathing deeply for a few minutes or more allows my body to reset. The higher up we are, the more protracted and worrisome the heaving of my lungs is, the more embarrassed I am by what I am going through, and the fact that I am lagging increasingly behind the rest of the group. The fact that I regularly stop and take photos doesn’t help my cause either. I aim for any rock that is flat and high enough to sit on so as to improve my ability to relax. And yet there is also some irony to the fact that when I get up to continue walking, I walk briskly as if there had been no issue – until I feel as if I was hit by a truck, and have to stop again almost immediately.

There are regular orange staves protruding from the ground along the trail indicating 200 metre increments. On such a difficult trail, 200 metres seems like a very appropriate frequency to post distance markers, and certainly more of an incentive to bedraggled hikers such as myself. There are also regularly-spaced instances of piles of rocks intended to mark the trail when it disperses across the rock-strewn ledges, as there are numerous possibilities for ascending or descending the mountain in these zones.

The vegetation on the mountain is similar to what is found at lower elevations, only sparser. The freilejones only grow at higher elevations, and near the summit, the vegetation is absent. At lower elevations, the vegetation appears to be heath-like, rich is small, delicate plants and a variety of mosses. Animal life is altogether non-existent, be it avian or mammalian. The reason for the paucity could be poaching, given the relatively small size of the park region.

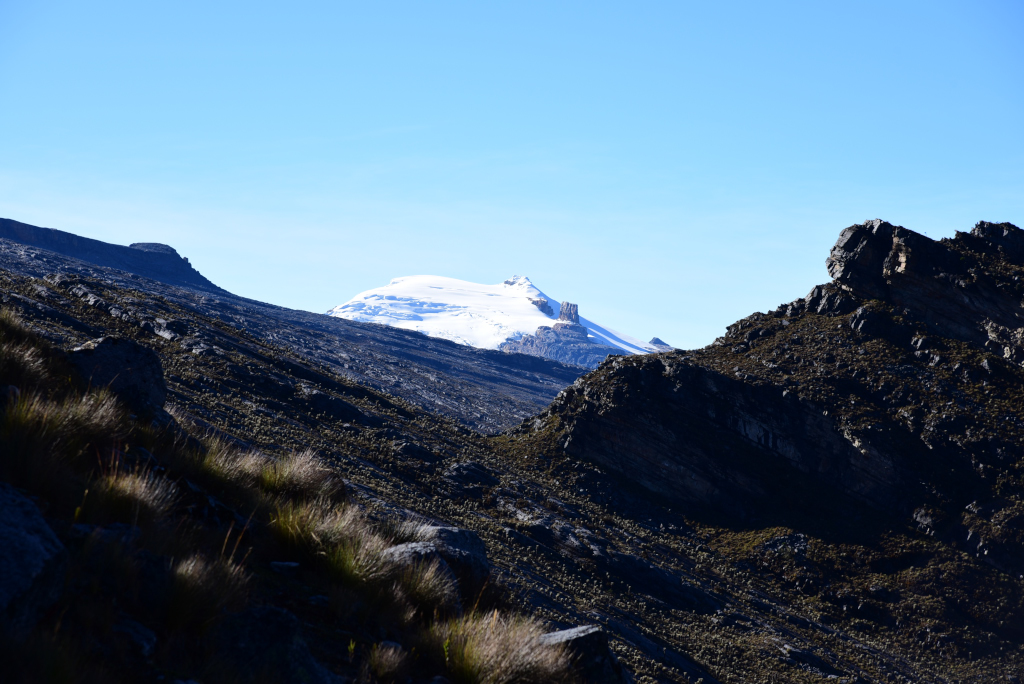

The trail climbs steadily amongst the carpet of freilejones as the huge ridges flanking the mountain peak come into view. Signs are posted at intervals, providing descriptive information pertaining to the park as well as the trail. The snowfield crowning the sendero de Ritacubas grows in dimensions the higher we climb. Beyond a certain elevation, the Pulpito del Diablo – one of the Cocuy’s peaks – is visible, set against a crown of snow, to the far right of the mountain we are climbing.

Rising through the fields of freilejones, shallow creeks appear, their water gurgling merrily amidst the rock and grasses, or rushing across wide rock slabs. As safe as the sendero is to climb now, it would be an entirely different story in the rain, as much of the trail crosses sheer rock surfaces at a steep pitch.

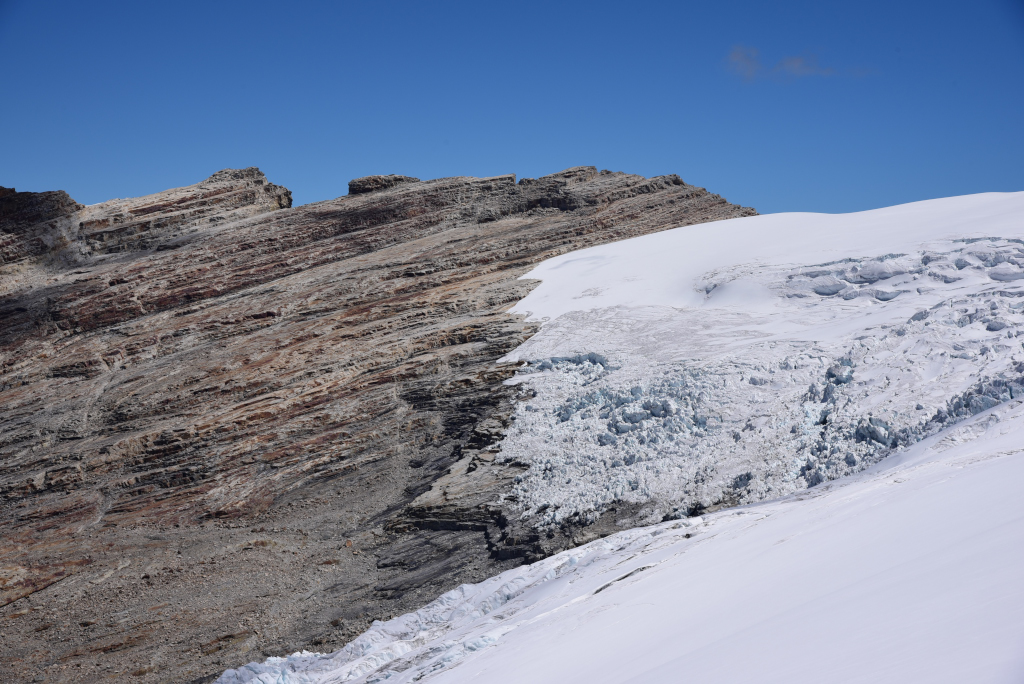

Even the appearance of the snowfield above us is deceptive, as the trail extends a substantial distance across rock ledges, culminating in a massive ledge until reaching the territory of the snowfield. At the far end, the ridge abuts the snowfield, offering dramatic views of the mass of snow piled up at the summit, and enveloping the small massif at the peak. Apparently, it was once possible to trek across the snow to the peak of the mountain, from which views of the tropical llanura far below would be visible, but it is no longer allowed.

The French-Canadian that started at the same time as us and disappeared quickly on the trail ahead of us reappears near the beginning of the huge ledge that leads into the snow pack. He is climbing all of the highest summits in Colombia, and is probably doing the same in other countries as well. Regarding my physical state on this hike, he confirms that the fact that my fingers appear to be swelling is a sign of altitude sickness. However, if I pace myself and am sure to catch my breath often enough, I will not be left with any permanent lung damage. Well, that is reassuring!

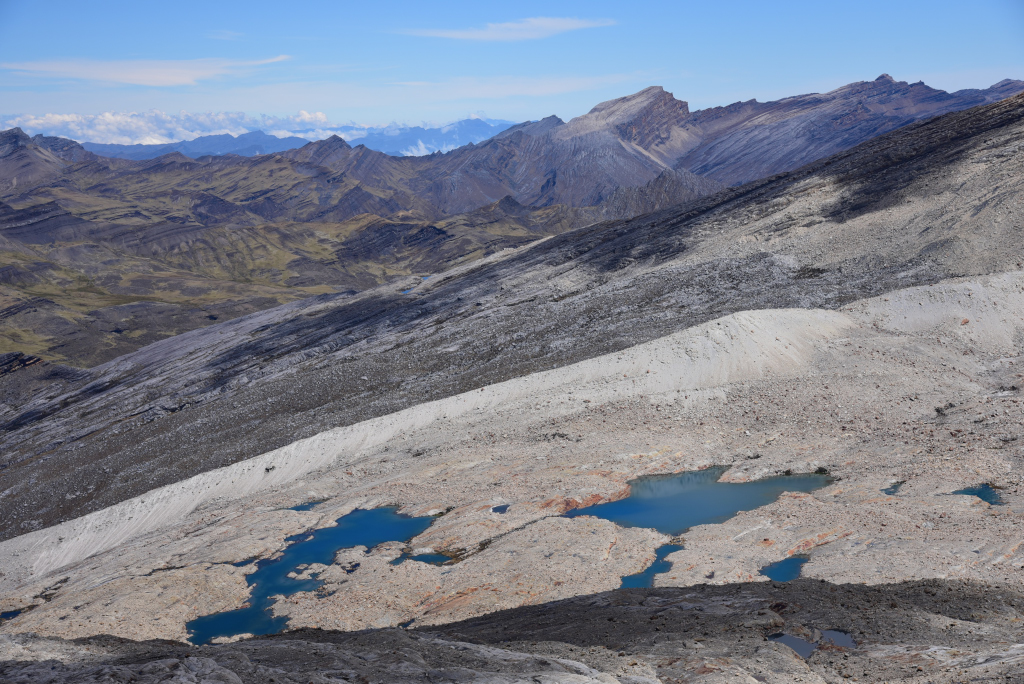

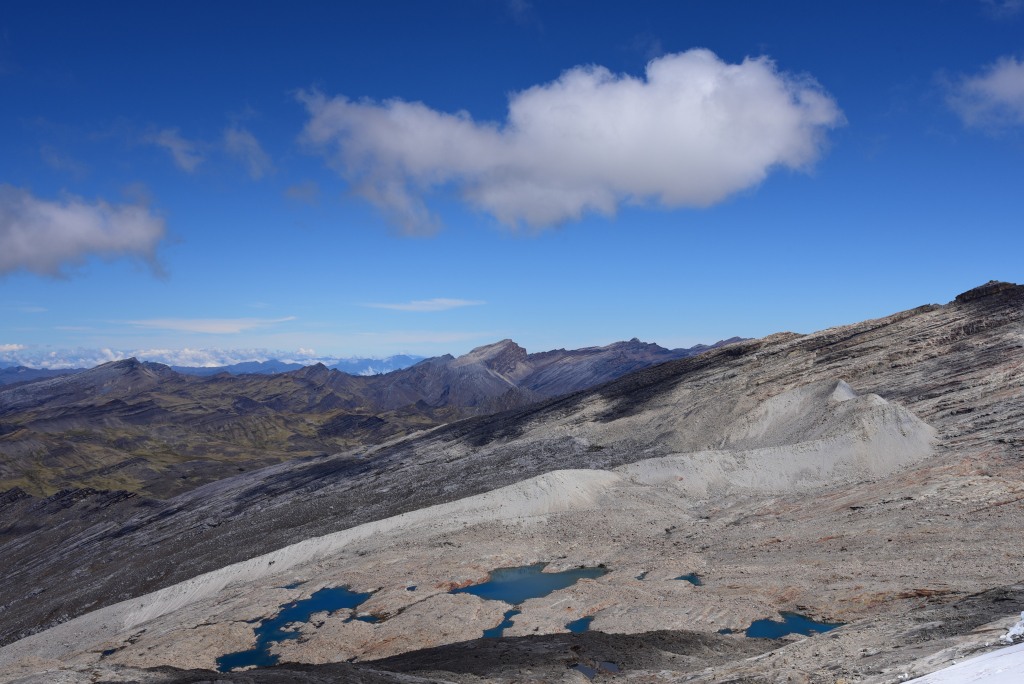

From the vicinity of the summit, dramatic views are visible of the play of light and dark unfolding across the dramatic landscape leading to the snow-capped peaks. My hiking companions are mesmerized by the vista of the glacier that caps the mountain and the snow spreading around the summit of the rock ledge leading to the snow field. Of course, I am far behind them, and only once they have been at the summit for some time do I trudge wearily to the culmination of the trail, in virtual disbelief that I have actually made it this far. I just want to collapse on the spot, but within a few moments have regained my breath and am also stunned by the spectacular views around us. Apparently, from the actual peak we should be able to see far below into the tropical frontier of Venezuela.

But there isn’t much time to for me to take in the beauty of the area around the peak, as we must descend the mountain as quickly as possible to avoid the clouds that typically move in in the early afternoon. The few heavy rain clouds that do approach over the mountain move lazily, the warm and sunny weather slowly becoming darker and colder. Since we are dressed for cold weather to begin with, the dropping temperatures make little difference to us. The descent down the mountain seems inexplicably arduous, perhaps because most of the trail is loose rock fall, and simply much longer than I had remembered. Yet nearer the bottom, the sun returns, and stays with us most of the afternoon.

Jorge waits for me patiently to get up and continue walking, never losing sight of me, even though the other two are far ahead of me. He insists that it is totally fine, tranquilo he repeats, refusing to be phased by my inability to make much progress. Kudos to him, also for insisting on whistling to the others to ensure they have not strayed from the path. He emphasizes that his responsibility as a guide is to make sure the group stays together and is safe. It may seem like a trivial issue, but it isn’t – even here, things could go very wrong very quickly. As is obvious in my own case …

Jorge tells us he has his own house where we could stay instead of La Esperanza. My first impression is that he is trying to cash in as much as possible, but then given the competitive rates he is offering, the very likely probability of doing a more appropriate job of accommodating tourists than some of the other cabañas in the area, our own in particular, then why not. 30,000 pesos for individual rooms, as opposed to 80,000 for a claustrophobic room with no privacy, and competitive rates for food that seems way better than the slop we are being provided in our current establishment seems very enticing! And his rooms are available now, which is great. It sounds too good to be true – except that he has done a great job with us so far, and has been an excellent guide as well.

He tells us his place is at La Capilla, but where could that be? Until it dawns on me to go with the obvious choice, and that is the chapel in the encampment that we passed by yesterday. Yes, his place is next to the Capilla. And how far from the starting point of the hike? The same distance as La Esperanza – one kilometre.

Finally, we reach the lower echelons of the hike, the marshy plateau with golden pampas grass lining the quebrada, evoking a bucolic sensibility that is far removed from the massive mountain we have just climbed. My lungs are in pain and I occasionally sit down, although the path is now well-defined, largely bereft of the loose rock that has plagued most of the descent. The freilejones are still in evidence in these lower elevations, one grouping in particular standing out for the size of the trunks. Jorge tells me they are 500 years old, which seems incredible.

Recapping the day’s hike, the flat approach to the mountain through the marshy freilejones rises steeply along a twisting trail of loose rock, climbing through the carpet of freilejones and pools of water, then further up, running along a massive shale and limestone ridge. The trail weaves through loose rock fall on sheer rock faces, then clearing a massive ledge to the left, another huge shale ridge rears up to the side, the huge snowfield gradually coming into view, accessed by means of a massive ledge that pivots upward towards the mouth of the glacier.

Looking back at the massive peak behind us, it is difficult to imagine the climb would have been so lengthy and difficult. The peak recedes in the distance, the distinct zones of the ascent diminutive in the vista now blending into each other. On the last low ridge, and we approach the crumbling cabañas we had originally thought about staying upon arriving yesterday. In their environs, the grass glimmers bright green in the mid-afternoon sunshine, and the creek that originates higher up the mountain flows to the back.

Seated on the benches in front of the cabañas, John repeats how he can’t believe he actually completed the hike, and that he would have never have considered doing the hike if he had known it would be so difficult. I find it hard to believe, given that he was often far ahead of me, walking easily while I was typically crawling at a snail’s pace, then having to stop every few feet. I guess challenges are all relative!

I am debating whether I should even do the hike on Wednesday. The elevation has turned out to be a major issue for me, making the hike a tortuous experience. Even if I were to be OK with going as agonizingly slow as I did, it wouldn’t be fair to the other person I am hiking with. There is a possibility I could acclimatize by Wednesday, but given the experience I had today, that seems patently unlikely. One possibility for mitigating the agony of the hike on Wednesday is taking another round of the altitude medication. I took it initially in preparation for my trip to Bogotá, but Bogotá is situated at 2,600 metres, whereas we are hiking here from 4,000 to 5,000 metres.

David tells me he may want to continue after the hike on Wednesday straight to Güicán, then continue thereafter towards Bucaramanga via Capitanejo, although he is concerned about the reliability of the bus, never mind the poor quality of the remote roads. It would seem very romantic, but if anything goes wrong, it will result in a lot of trouble. I had originally intended on returning to Tunja, then possibly spending a few days in Iza by Lago de Tota prior to returning to Bogotá, but I just don’t want to face another night in Tunja. In Bucaramanga, I would get an AirBnb and regroup, but then I am back to the drawing board as to how to get back to Bogotá on a timely basis, since it is even further, and I just don’t want to have to traverse the highway between Bucaramanga and Tunja again.

At the hostel, I ask about the other two rooms that remained empty yesterday, despite having been told that they had been reserved yesterday. I am told the rooms have been pre-booked by people that have experienced problems with their vehicle, and the staff doesn’t know when they will arrive. I have the feeling that the story may be made up, just to extract the most money out of us. Meanwhile, our room reeks following multiple bathroom visits, without any possibility of being airing out.

It’s one thing to have to sustain your own undesirable odours, but entirely another to have to tolerate those of an unrelated party. That and other luxuries, all for the price of a personal room elsewhere. I would have left if I wasn’t reliant on John and Kim for transportation. I don’t stay in hostels for a reason! I would love to lie down after the long arduous hike we did today, but the stench in the room is unbearable.

I search for the appropriate place to hang my clothing. Everything is soaking wet, and I have little else to wear. It is so cold and damp here, and of course the place is not set up to accommodate the drying of hiker’s clothing with a quick turnaround in mind. At least I had the foresight to take thermal underwear along on the trip! The sun is shining in the front of the house, but the idea of laying my clothing on some surface to dry becomes moot the moment the pack of juvenile dogs sets on me. The clothes would just end up rags. That leaves the interior courtyard, which seems to be at least temporarily graced by sun.

I have grown used to walking around bent over, simply to avoid smashing my head into low-lying protrusions, lines, door frames, shower rods, etc. So sitting at a table and writing, with the spectacular views of the mountainsides around us shining through the windows is hardly the worst option. In the kitchen, the staff prepares what may turn out to be another regrettable meal … Kind of an underwhelming way of wrapping up such a spectacular day climbing one of the local mountains – even if most of it was subject to severe huffing and puffing! But the power of the experience will remain in the form of the stunning photos I took of the trek …