September 14, 2018

Today’s journey takes me to the east side of the Alster, beginning again at the top and descending into the old city, exploring some of the local attractions in the respective areas. As with the west side of the lake, the areas immediately adjacent the lake are characterized by consummate luxury. The weather is also holding up well for the long walk, which will take me through the Isemarkt, probably the most famous outdoor market of the city, among the affluent villas of Harvestehude to the shores of the lake, south to the iconic Dammtor train station, and then to the area of the canals of Speicherstadt that comprise the ancient commercial core of the city.

Harvestehude is bordered on the east by the northern part of the Außenalster and capped from the west to the top by the Isbekkanal, canals being ever-present in this maritime commercial city. The canals have long since lost their importance in terms of transporting goods and people, and are nowadays largely decorative, also serving as outlets for recreational boating. While the area encircling the Eppendorfer Baum U-Bahn station is somewhat unassuming, further towards the Alster the ostentation of the neighborhood is flagrant.

The reason for my visit to Harvestehude is the iconic Isemarkt, which stretches out along the Isebekkanal between the Eppendorfer Baum and Hoheluftbrücke U-Bahn stations. Confusingly, even though the U-Bahn is specifically intended as an underground train (“U” stands for “Untergrund”), it runs atmospherically through substantial sections on elevated platforms, offering charming views of local neighborhoods.

In a country celebrated for its engineering technology, Germans place an enormous importance on tradition in other respects, one example being the consumption of traditional food and drink, going out to German-style taverns and cafes, and buying food in markets. While buying food at rock-bottom prices in warehouse-style stores is de-rigeur for many, the outdoor food markets are holdouts from a different era, and popular with locals and tourists alike.

A passage leads through the market under the industrial-age trusses above us, the stacked boxes of goods and display vitrines of the vendors lining both sides. Despite the apparent linear arrangement, the sheer amount of merchandise and people make lend the market a maze-like quality. The vendors’ wooden bins are overloaded with all manner of locally farmed vegetables, flowers, spices, and teas and coffees. A vast array of local and European cheeses are displayed in glass vitrines, the aroma of traditional sausages wafting from the butcher’s wagons, with the facades of elegant country-style apartment buildings peering from behind the vendor’s trucks that line the market.

Harvestehude’s name is derived from the former name of the local St. John’s Monastery, Herwardeshude, which had been located in Altona near today’s street and small stream of Pepermölenbek at least since 1246. Herward was a common name in the 12th and 13th century, so it is assumed that the name means a stockyard near a ferry dock (Hude), which was founded by a man called Herward. Later, in 1295, the monastery moved to today’s Harvestehude area, transferring the monastery’s name to the new area.

I meander along the alleys and broad boulevards of Harvestehude, the opulent residential complexes and villas bathed in greenery, the sky overhead blue, punctuated by a smattering of light clouds. Very little traffic is present on the streets, or for that matter foot traffic. So close to the centre of a major European city, yet the area feels like some remote country setting. A few verdant blocks to the east lies the Alster, with its views over the calm expanse of water and the skyline of the old city to the south.

The sky opens up along the Alster, the broad dirt paths an inviting venue for the public seeking a bucolic retreat from the stresses of the world. The heaving willows open up to the expansive views of the city and the enormous blue sky above us. Recreational and passenger boats ply the waters of the lake, today far fewer sailing boats in evidence than the day before. On the water, kayakers, rowers, and paddleboarders are in evidence, and along the shore, the obligatory seniors feeding the ducks.

Since 1800, distinguished and rich Hamburg citizens built mansions at the bank of the Außenalster lake, to move from the city to a better surrounding area. An example is the building at Alsterufer street #27, built by Martin Haller—the architect of the Hamburg Rathaus. The building was later owned by Anton Riedemann, the founder of Deutsch-Amerikanischen Petroleum-Gesellschaft, which later became Esso. As of 2009, the Consulate General of the United States in Hamburg has used the building.

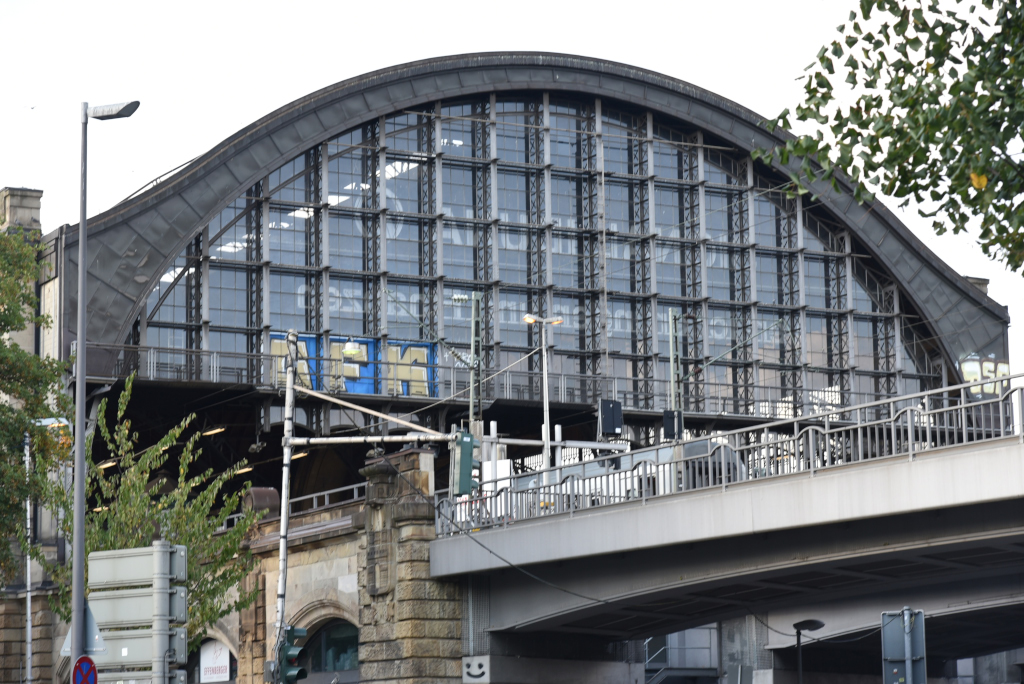

South of the sprawling expanse of villas and luxurious residences, parks and privileged educational institutions that mark Rotherbaum lies Dammtor, the city’s other major train station (Hauptbahnhof immediately to the east being the primary one), the hub of many local and national trains. The station is characterized by a vast glass-encased, industrial-age structure that towers over the surrounding area, and also marks the boundary between the bucolic areas to the north and the extravaganza of seediness that Sankt Pauli to the south is notorious for. And yet immediately around Dammtor is one of the city’s iconic urban and park complexes, the Messe und Congresszentrum and the the Planten un Blomen park.

Sandwiched between Sankt Pauli and the Altstadt lies the Neustadt neighborhood, ironically named, given that it is essentially part of the core of the old city. It is home to some of the most iconic locales of the city, including the Staatsoper, Gänsemarkt, Jungfernstieg facing the Alster, and the Elbpromenade along the Elbe river. The area is rich in architecture and sightlines, unquestionably one of the most spectacular parts of this beautiful city.

The area is home to a concentration of commercial and residential architecture that tends to blend turn of the century northern German commercial sensibilities with the ultra-modern, largely motivated by the extent of damage the area suffered during World War II. As striking as the area may be, it lacks a strong retail presence, hence the absence of foot traffic, the ubiquitous construction making navigation even for pedestrians unnerving.

The Alstadt looks very similar to the Neustadt area, both forming the historic core of the city, with Sankt Pauli to the west and the Fleeten canal area to the south. The Alsterkanal joining the Binnenalster with the Elbe river to the south forms the dividing line between the two districts. The Altstadt is also a collage of old and new structures clustered around narrow winding streets, much of the area reimagined after the massive destruction of the second World War.

The area of today’s Altstadt featured a minor Bronze Age settlement in the 9th or 8th century BC. In the 8th century, Saxon merchants established what was to become the nucleus of Hamburg: the “Hammaburg”, then a refuge fort located at today’s Domplatz, the site of the former cathedral. Under Frankish rule, a baptistery was installed in 804 and Hammaburg strengthened by Charlemagne in 811. It grew to a sizable market town, was declared a bishop’s see in 831, and an archbishop’s see a year later. For the next 600 years, the history of Altstadt was that of the city of Hamburg.

By the end of the 15th century, the then Hanseatic city-republic and free Imperial city had accumulated various territorial possessions in its hinterland. Eventually, Hamburg’s 13th-century city-walls were extended, first in the 1530s, then again in the 1620s to include all of adjacent Neustadt.

Regarding the urban history of Altstadt, only a few structures prior to the 17th century are left, due to repeated damming and diverting of the Alster and its canals, the Great Fire (1842), the bombing in World War II (1941–1945) and modern infrastructure projects (particularly during the 1880s to 1900s, 1920s and 1950s to 1970s) having left Hamburg’s inner-city with a mainly 19th and 20th-century built environment.

The now-ruined Sankt NikolaikKirche was a Gothic Revival cathedral, formerly one of the five Lutheran Hauptkirchen of Hamburg. The original chapel, a wood building, was completed in 1195, and was replaced by a brick church in the 14th century, which was eventually destroyed by fire in 1842. The church was completely rebuilt by 1874, and was the tallest building in the world from 1874 to 1876.

The bombing of Hamburg in World War II destroyed the bulk of the church. The removal of the rubble left only its crypt, its site and tall-spired tower, largely hollow save for a large set of bells. These ruins continue to serve as a memorial and an important architectural landmark. The remains of the old church are the second-tallest structure in Hamburg.

(Narrative excerpted from Wikipedia)