March 31st, 2018

I wake up groggily to the sound of my alarm clock. I got far too little sleep, as usual. These evening Semana Santa processions are killing me. I check the news and my email, and need to get back to bed again, at least for a last spurt of beauty sleep. Shortly after lying down, loud banging and clanging nearby. I tend to confuse noise emanating from the neighbors with activity next to my house, however, it seems just a bit closer than normal.

And it is: the neighbor and a woman who I presume to be the cleaning lady are unsuccessfully trying to enter the house. I confront them: you didn’t bother ringing the bell? I am here until tomorrow morning? The neighbor smiles and gives me some vague excuse, but I find the whole debacle strange. At least I will be rid of the garbage stinking up the laundry room …

I arrive at the bus station early enough, however exhausted I may be. The positive news is that according to the taxi driver, the day is supposed to be sunny, which I find hard to believe, but if so, my timing is perfect. Matters unravel inside the terminal, where it takes me a while to find a bus company that services the Puracé national park. The next bus leaves at 2:30 in the afternoon – and it is only 9:30 am? I don’t think so … some other company must have service to the park.

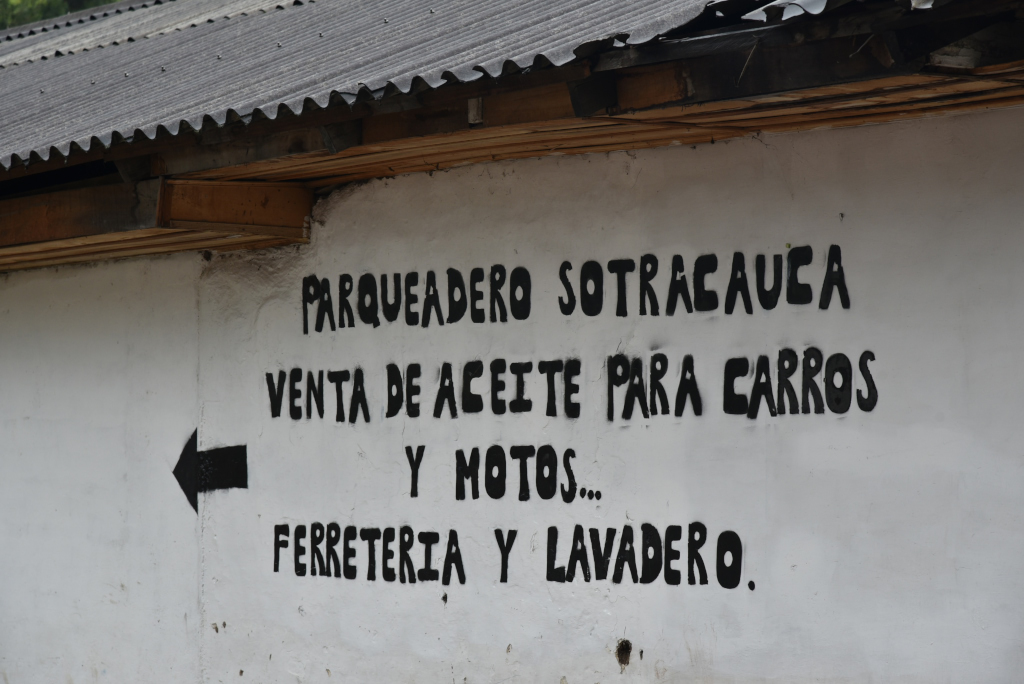

I go on a wild goose chase in the terminal for the appropriate bus company. Cootranshuila does not go to the park, while another provides service to Coconuco, but not to the park. Adding flavour to the information gathering session is locals blithely cutting in line ahead of me. I lash out at one individual, which elicits a surprised response from the crowd gathered. I think of what I was told a few days ago, that outside the centre people are pushy, vulgar, uneducated, and of a generally low ethical standard. Fair enough! Back to Sotracauca, where the agent explains to me that limited service is provided since so few people go to the park, and no, the entrance to the park is located a long way from the highway joining Popayán and San Agustín.

There are two buses, one at 5 am and the other at 2:30 pm, which allows people to have enough time to visit the sites, then return home. Dejected, I realize that I will not be visiting the Puracé park, and then tomorrow is my last day in town as well. Perhaps Coconuco could serve as an appropriate alternative? The family and friends from Cali are themselves trying to figure out how to get to Coconuco, pointing me to the bus I need to take. More in the line of bus station brusqueness, I am waved towards the 5015 bus – but where is that? The bays are numbered with double digits, and none of the buses are numbered 5015. Several of the drivers I ask wave me in the general direction of the bay dismissively. Finally, another driver approaches me to tell me his bus is going to Coconuco – but it isn’t the 5015.

Two young locals sitting behind me on the bus tell me there is some waterfall a half hour further on from the Coconuco. But how to get there? No one seems to know, although they show me a short video clip they found on the net. More on the subject of the poor organization of tourist resources. The trip takes us through the shambolic suburbs of town, scaling up in quality slightly as we approach the northern periphery and the incline leading into the mountains to the east.

The road winding through the green ridges is still familiar, looking increasingly dramatic as we weave higher and higher into the clouds. And for whatever promise of the lack of rain might have been applicable to Popayán doesn’t hold at this higher elevation, the droplets sprinkling on the windshield as we rise further, progressing to a light rain. Whatever Coconuco holds in store, the prognosis for dry weather does not look very positive at this point.

The small side road I had seen branching from the highway on the trip from San Agustín is in fact the access road to the Puracé national park, which is signposted at 12 kilometres. If that is the distance to the park boundary, I am not getting off here. Perhaps I could walk back from Coconuco to the encruce and flag down a car heading into the park. But alas, that will be unrealistic as well.

The road rises some considerable distance further to the town of Coconuco. The town looks like it may have some promise, but the appeal are the hot springs, which I am assuming is just a stroll away. Passengers disembark from the buseta and due to the rain, huddle under the eaves of neighbouring buildings.

There is general confusion as to where people are supposed to go. An older man on the street assures me it’s just a 15 minute walk away. I decide to walk to the hot springs, but then am waved to a pickup truck by one of the members of the party I met in the bus station earlier on. I climb into the back, and embark on the ride of my life. At first the passage seems relatively straightforward as we drive at relatively high speeds along paved roads, but then the vehicle slows down due to heavy rocking as we continue on a rough country road. The dramatic countryside rises around us, partially veiled in the rain, patches of forest, pastureland, soaring hills, the air increasingly chilly, and the rocking increasingly violent. The hot springs were a 15 minute walk away from Coconuco? Seriously? At this rate, we will end up in Huila!

Finally, after almost an hour of driving, the vehicle slows down and stops on a muddy, rocky patch of mountain road, the green world around us soaking wet. I could well imagine doing something far more appealing and comfortable, rather than having spent hours on this journey, having started too early, and having been thrown back and forth for the last hour. My cohorts seem far more motivated to be here, however.

We squeeze past the parked cars to a gate, where we are cheerily asked for COP $10,000 for the privilege of being here. I look around at the soggy mess of fields and hills. There are a few small cabins below, but nothing else is visible that would smack of organized attraction of any sort. ‘No thank you, just here to take some pictures, then leave’. Not the response that was expected, but what the heck, this place doesn’t look like much, and I had a very different experience in mind for the day.

It seems that the shacks I see below me are in fact the alleged hot springs. There are two small houses, which seem to be changing rooms, while to the side are several pools with hot thermal water. Cold water is offered from a shower, the adjacent stream, and a waterfall tucked away in the bushes. Visitors slowly clamber downhill along the muddy embankment towards what could vaguely be referred to as facility, where they are greeted with uniformed attendants who give them the tour of the area and instructions as to how to proceed. I am happy to head towards the empty restaurant to enjoy a terrible coffee. $1,500 for the use of the toilet makes a fairly cogent comment on the attitude of whoever is running this place.

In response to my comment that they could beef the place up a bit for the admission they are charging, I get a placating statement extolling the virtues of the naturaleza. I could in theory embrace this vision, but not for the bone-jarring ride up here, the admission being charged and the paltry attractions. But Colombians look for an excuse for a fun family-style outing, and while this may not evoke Club Med, it is great for whoever seems to be coming here – and the numbers grow as the hours pass.

A number of people lounge in a small concrete pool apparently fed with hot water. Below rushes the creek, which is one of the outlets of cold water, very natural indeed, and to the back, a trail that leads past the medicinal mud bath to the waterfall. On the other side, past the changing cabins, another larger swimming pool. Partially-dressed locals clamber unsurely along the muddy trail to their next destination while I follow them with a camera. Taking photos of people here may not be entirely tactful, but I just want to document my morning prior to making my way onwards to somewhere else.

The social feeling of the visit trumps everything else, from chatting in the pools to mucking around the mud bath. The culmination of the experience is the trip to the waterfall, carefully clambering along the wet rocks to the picturesque pool and cascada, already upon my arrival full of half-naked revelers. Irrespective of the wet, cell phones are handy for photos, although I am sure at least several people will have less functioning phones as the day goes by. My appearance is cause for ramping up the energy, although it is hard to get decent photos of anything with the number of people clambering around.

Having taken the obligatory photos, I climb back up the muddy trail, leaving the soggy mess that passes off as one of Cauca’s star attractions, and embark on the next part of my journey, downhill along the very muddy, treacherous trail towards the town of Coconuco. The landscape reflects a return to the classic Colombian green hillsides soaring above peaceful valleys, sprays of exotic flowers erupting from exotic bushes and trees, small dairy farms and other agriculture ventures, a narrow, rudimentary road winding wildly through the countryside, a few houses scattered through the valley and along the steep ridges around me. And the cold pouring rain, another constant in the country, although it has really only begun in earnest this week. What a way of celebrating Easter – I won’t complain about lousy weather for Easter again!

The persistent rain is making it difficult to use the camera, and more importantly, running the risk of seriously damaging the camera with constant exposure to water and dampness. I carry the camera in a compact camera bag, and also have a dry sleeve, but ultimately the camera has to be removed from both in order to be used, and being too protective with the umbrella also automatically reduces light conditions. In virtue of my backpack being exposed to the rain, the camera bag also is superficially wet, and quite damp inside. Alone the process of removing the camera from its various protective layers causes it to get wet.

The rain does not abate. I continue walking towards the town of Coconuco, and the rain only seems to get stronger. My pants are now splattered in mud and wet, and my shoes are soaked. In this wet damp weather, it is impossible to dry clothing, particularly since there is no heating in houses here. I have no idea how the people living in these modest shacks with no insulation of any sort cope.

The journey on foot is lengthy, not surprisingly, considering how long the drive up to the hot springs was. And walking is not particularly easy, considering in what rough shape the rocky road is. The idea of continuing to the Puracé park is not happening, given how far away I still am from Coconuco, Coconuco from the encruce to the park, and then the park entrance itself, never mind the pouring rain. The trip to the park will have to wait for another time, and definitely not in such a rainy period!

My heart sinks at the number of vehicles passing me on the road to the hot springs. It was crowded when I left – I can’t imagine what it will look like by the time I return to Coconuco. Colombians may be social animals, but the alleged nature experience would be more reminiscent of something along the lines in India, where the numbers are always overwhelming.

Dairy farms with placid jersey cows graze the green grass, occasionally breaking their cud-chewing concentration to stare at me as I trudge by. Mist rises magically over the verdant hillsides, the tree cover a shifting portrait of deep green and then white in the rainy landscape. The road is rough, muddy, and barely walkable, although the motorbikes passing almost entirely covered in rain capes probably are best suited for this journey. In stark contrast, the brilliantly coloured exotic flowers that never cease to hypnotize the visitor. The streams flowing through this fecund landscape are gushing in celebratory pleasure, overflowing with the plentiful rainfall that has inundated this land in the past week.

At one point, some locals with a young boy rush into the road, telling me that there is a path I can take to save the curve, which seems to imply that that the road embarks on an extended loop which rejoins a linear drop, only lower down. Fair enough, except that as scenic as the deep grasses we wade through may be, they virtually guarantee that I will get soaked from the get-go. I issue my thanks and return to the road, not that I won’t get soaked in the end anyway. The dark, weathered skin, intent dark eyes and aquiline features suggest what I see confirmed on signs closer to town, that this is an indigenous region, which leads me to ask myself what the contemporary presence of native culture is in the country, given the degree of integration hampering visibility of said cultures. No one is jumping up and down screaming ‘We’re native!’, but much of the country does have very strong indigenous culture roots, if not a contemporary cultural presence.

On the main paved road leading to Coconuco, I am surprised at the amount traffic in evidence, although it takes me time to realize that this isn’t a village road so much as the highway to Huila, so the amount of traffic makes sense. The countryside is spectacular as always, the rain finally having abated somewhat, but walking not much easier, given the amount of water flowing across the paved road.

A small empanada stand beckons, which normally I would dismiss, but I am hungry, wet, and the scenery is spectacular. More importantly, it seems the empanadas are being freshly made, which is appealing. On the table next to the artisanal empanada production sit a few rows of cups with strawberries with cream. I try one; big mistake, but for the right reasons. Being someone quick to decry the quality of Colombian dairy products, I have to admit that this is spectacular, the cream fresh, rich, drowning the equally fresh strawberries, not something for the faint of heart.

The empanadas are different altogether, but fresh and very tasty, the stuffing dried peas, potatoes and onions, and as the owner of the stand assures me, a specialty of the Puracé region we are in, and pretty much the same as I ate on the trip to Popayán. Dairy and strawberries are specialties of the region, which would account for some seriously troubled arteries here.

Past the lush, verdant scenery, the rains having stopped, but my things soaking wet. The road descends further, the increasing density of the sprawling houses suggesting that the town may finally be close. And there it is before us, spreading out along the roadside, sandwiched in between the two hillsides. Straight ahead, and at third intersection turn right, and you will find the buses to Popayán. But in the appearance of the newfound afternoon light, Coconuco does appear to warrant more attention than as a transit point to Popayán.

The brand-new green-and-white apartment buildings set to the back of the traditional houses are unexpected in this traditional burg. Typical of so many small Colombian towns, many of the faces on the street bear strong native features, but not all. The people on the street are restrained and yet expressive, calm but quick to smile. What is always visually arresting in the small Colombian towns are the contrasting colours that seem to arise between select buildings, vehicles, peoples’ clothing, flowering bushes, and so on.

And as in the most insignificant towns, there is a small plaza, effectively a somewhat visually arresting church set on a set of recessed terraces extending out from the main road. The only sign of life are two young boys playing some indeterminate game. A few flowering bushes and a stone fountain round out the mix, to the rear the landscape erupting into a fogged in sea of vertical green. And across the street, fresas con crema, forbidden fruit at the best of times …

Back in Popayán, I decide to walk from the bus station and make sure that no police officer offers to drive me into town. Little idea do I have how interesting that walk will be. Straight ahead two traffic lights, left one, and then straight ahead, I am told. Immediately on the other side of the boulevard is a large, sprawling chaotic street market that has a very third world feeling to, and as such is very refreshing. The best in Colombian street food is offered from the stands woven across the muddy road, large stores on either side offering the necessities of life. The allure of the market slows me to a crawl, and then I continue along the wide boulevard, now limited to a few ambulatory vendors and well-tended stores along the wide sidewalk.

What I didn’t expect is the large-scale artisanry market at the Centro de Convenciones, a series of food kiosks erect around an outdoor seating area facing a large stage on which a traditional ensemble from the Pacific coast is playing. I would stay longer, had I known the music is being presented here, but I didn’t. But then how is someone supposed to be aware of all the things that are going on in town during the Semana Santa? There doesn’t seem to be any unified vision for publicity. All of the attractions I have found here so far have just appeared to me by chance.

I am not particularly interested in tipico gastronomy, as there is little chance of ay unique gems appearing. The music is great in theory, but I want to explore the indoor market before making my way into the town centre. Dozens of booths vie for the visitor’s attention in the spacious, well-lit hall. Much of what is on display is whimsical, quaint, inexpensive, cheap knick-knacks that look good on your grandmother’s shelf. Timeless artifacts are not to be found here, well, perhaps at a few of the stands.

While the vendors offering their wares inside the convention centre are relatively conventional in their offering, it is exciting to see another craft market compliment the offering of activities available to visitors. The quality and scope of products offered may be limited to what effectively could be termed kitsch, but it would be no different to what I would find in the rest of the country.

At a coffee stand, I am lured in by the story of coffee grown on fincas by ex-FARC combatants, which seems like a useful cause, despite the coffee being unexceptional. Again, with so much work done to make such events happen for the showcase Semana Santa, why not do a better job of attracting people here with holistic publicity that describes all the attractions in town in a single publication? Rather than requiring visitors to stumble through and discover things by chance …

The Centro de Convenciones is just outside of the town centre. Life on the street has its own colour here beyond the musical stage in the parking area, including the food trucks and stands outside selling snacks. At the coconut and panela stand, I am asked about the quality of coconut in my country. Well, that’s a bit of a complicated story I don’t really want to go into at the moment.

Colombian food? Don’t get me on that subject either, but the coconut and panela the vendor is cooking in the large pan on low heat is a remarkable delicacy, as much as it represents an excessive indulgence. We get into another major subject, coffee, which leads me to finally part ways with my conversation partners, as it is getting late in the afternoon, and I had wanted to get a coffee at the Ricolata prior to heading home and getting some reasonable rest before attending the final Semana Santa procession.

I am eager to see what kind of photos I can achieve today using the newfound variable ISO setting on my camera, allowing me to automatically take photos without the use of flash in low light situations. I am directed towards the Parque Caldas, where the light would be preferable, which of course makes sense in terms of the richer backlighting. It occurs to me that the impression of the procession changes in terms of the ambient lighting, ranging from halogen lights, gas lamps, fluorescent, or none whatsoever, altering the manner in which the tones of the fabrics, metals, instruments being played etc. are perceived.

Next to me, a group of Argentines from Buenos Aires on a photo safari for the Semana Santa. Everything looks just perfect – except for the grim police officer who almost deliberately blocks our view. I can understand that he has to stand somewhere – but in front of the line of sight of a group of photographers? Being a deliberate pain isn’t a Colombian thing …

Despite the impression that the procession is extremely slow, it actually proceeds at a relatively brisk pace. The pasos appear to be carried out of the cathedral to our immediate right, then disappear along the road running to the west. The crowds along the street become rationalized, moving to the side of the road and behind the barriers in order to provide a clear path for the last procession of the Semana Santa.

More delay as the floats make their way through the blocks to the south, and then it comes, rounding the corner of Carrera 6 and Calle 5, first the drum-and-lyre marching band, the sound of the rolling percussion of the drums thundering through the alleys. The military brass band follows with its saxophones, trombones and trumpets, green uniforms and white helmets matching with white boot leggings. The cordons of candle bearers file along the side of the road, solemnly walking past us.

The first paso is a giant candle, carried by cargueros dressed in white robes and head scarves, and brilliant red sashes. They approach the corner, wait, lift the paso, then continue past us, stopping just past us, their profile illuminated by the powerful halogen lights erected along the tops of the buildings.

From this close position, the look on the faces of the cargueros is visibly intent, and the weight of their burden palpable. More pasos pass by, the statues of Mary surrounded by candles and voluptuous bouquets, framed by ornate silver medallions, and the cargueros again in white and red. The ages of the cargueros vary. I recall that their positions are hereditary, passed from one generation to the next.

Another marching band passes, this one with woodwinds and brass, the huge white tubas at the back standing out against the sombre blue uniforms, the percussive rhythm of the music setting the tone for the procession, whether moving or standing. The regidores stride purposefully back and forth, the commanding authority on the ground intended to ensure that the procession proceeds smoothly.

Tonight there seem to be less saumadores, and when they pass, they are always shrouded in darkness. And the most visibly female component of the procession. The archbishop and acolytes with their regalia pass by, powerful men of the church in this devoutly Catholic country. More floats follow: El Angel de la Resurrección, Sa Juan, the San Pedro.

And when the last statues of Mary Magdalene and Jesus reborn appear, the crowd cheers. The statues are flanked on either side by young women in lace cowls. The military band closes the procession followed by a group of military police in dark green uniforms bearing candles, disappearing into the bright lights.

I follow to get some final shots, part of the group of stragglers, street cleaners, photographers police and tourists wanting to catch the last glimpses of the procession before it heads north a block short of the Iglesia La Ermita, then continues its long return to the cathedral, where the pasos can be finally laid to rest for the year.

The group of blue-clad women in the Investigador Jucial uniforms can’t stop giggling every time they see me, reason to keep to the back. The procession turns up Carrera 3, the rows of shimmering candle flames gradually diminishing in size until I decide to turn around and make one final journey home along the silent streets past the police standing guard at intersections and the few remaining street vendors to my suburban retreat.