March 5th, 2015

Today I return to Yangon (formerly Rangoon), winding down a month’s stay in Myanmar. It seems very difficult to wrap my head around the fact that I have been here for a month. It seems the time just vanished into thin air. And then returning to Yangon after a 20 years’ absence, and in for a considerable shock at the changes that have taken place.

One last morning in Bagan, but a rushed one at that. Having returned back to town the evening before, the owners are again offering breakfast, which I forgo due a misunderstanding, but no matter. Surely there must be some place to eat at the bus station. I am escorted by a pickup truck from one hotel to the next, each party boarding very leisurely, leaving me thinking that I really could have been the last party to join the fray, rather than the first, and actually get some more sleep.

Unexpectedly, the young man who joins us at the Thante is actually from Philadelphia, having just completed a year internship managing the hotel. I am sure he has many stories to tell, but now he is focused on getting to Bangkok and then Pattaya for a few days of vacation prior to returning to the northeastern U.S. mid winter.

We still have time at the bus station, but virtually all of the rows of storefronts that were shuttered upon my arrival are again shuttered now. Perhaps too few businesses have been found to populate these shops, or too much money is being asked for the rent?

Unfortunately, neither of the two eateries open across from the Elite bus company office offers the breakfast standard of Shan noodles. An unremarkable hin and some side dishes garners a price tag of 1700 kyat, which seems fairly ridiculous for Myanmar, but such is Bagan.

The bus to Yangon ambles along the bumpy haphazardly asphalted road through the leafy and relaxed village setting towards the south, little indicating that one of Asia’s most important archaeological sites is present a short jump to the north. We even cross though a small town with traffic circles radiating into streets that run past several blocks of businesses in all four directions, and then we return to the village setting.

Slumped in my plush seat, I watch the somewhat uneventful scenery pass by, beyond the modest bamboo and thatch shacks, scrub and agricultural plots spread across the hot arid landscape, low hills visible in the distance, the greens still with some degree of brightness at this time of morning. Sealed into the air conditioned mobile glass cage, we are sheltered from the presumptive building heat around us. The blankets provided are hardly inappropriate.

Once we reach the highway, however, all traces of settlements vanish, and we seem to be the lone vessel floating along the concrete road bed southwards, the land bereft of human life beyond a few occasional shacks peering from the green landscape. As the hours pass, that unique bizarre Myanmar phenomenon occurs, the landscape simply remaining empty, without any towns appearing, in fact, not even any intersection of any sort. Perhaps people avoid this road as it is a toll road, but there is really no sign of life or connection to anything else in the landscape we pass through.

The American and I are the only foreigners on the bus, and as we relax in the comfort of our plush seats, watching the landscape slide below us, we talk about tourism in Myanmar and its challenges. He jumped on the opportunity to work somewhere unusual when the Bagan hotel internship arose at the completion of his Masters degree in hospitality management in Australia. However, he now regrets not having stayed in Australia, since he could have worked for several years following his schooling, and have had a greater chance at permanent residency. He loved being in Australia, but now it would be a lot harder to return. The country is very difficult to gain a footing in, despite being flooded with immigrants.

He asks me what I think of tourism in Myanmar, and I think I know where he is going with the subject. He nods his head as I tell him that the country is overpriced for what it is offering, and that once the country becomes less trendy, it will have to do a better job at competing with the much less expensive and more diversified tourist markets of Thailand and secondarily Laos and Cambodia.

Myanmar is simply not that unique in terms of what it offers, other than being a very rudimentary country removed from the world circuit. With hotel pricing consistently two to three times higher than its peers in Southeast Asia, it needs to readjust its thinking to be able to succeed. He adds that at a recent hospitality conference in Yangon, major hotel chains were quite blunt in expressing the opinion regarding the Myanmar hotel industry’s singular mindset on profit-taking at all costs, with ostensible negative long term implications.

Prices have been rising the last three years or so with no noticeable reinvestment, this year the rises halting, since the high prices seem to now be impacting the tourist numbers. Just as importantly, Myanmar lacks an appropriate backdrop of infrastructure that Thailand offers – you are not just paying for the quality of the establishment, but he services that wrap around the accommodation.

Most hotels no longer follow the permit regimen, simply accepting foreigners, even though they are not allowed to. On the other hand, where the government used to have a very relaxed attitude towards issuing building permits, now inspectors are enforcing building requirements, and many even larger projects have been shut down, adding to the cost and uncertainty around the hotel business in the country.

The slightly preoccupied and somewhat petit young conductor attends to the passengers by serving the syrupy coffee and then cashew croissants, not that passengers need any kind of attention, being able to watch movies to their heart’s content while steeply reclined in their seats. This is fortunately not the kind of crowd to indulge in the usual enthusiastic mastication of betel nut in the public environment.

I would love to sleep on the bus but am feeling slightly queasy, not so much as a result of the constant rocking (nothing like on the train), but because my stomach has not been doing so well in the last week, not that it stops me from buying a huge bag of locally-made potato chips which are actually quite good, and later on in the day, another package of sugary baked dough twists from the long row of roadside vendors.

The bus stops several times at roadside markets, one centering around a sprawling outdoor restaurant featuring a wide selection of Bumese hins, shockingly priced at some three times what I am used to paying and hardly that memorable, the typical local food virtually always priced incredibly low comparative to a la carte items of other provenances.

In the otherwise utterly empty landscape, we pass by exactly two small shopping malls that look like theater sets more than anything, with possibly a few cars parked in front. I take no photos, as it would just be too much effort for too little rewards. I could spend my time with my face pressed out the window, taking snapshots of those fleeting memorable moments, but while the landscape is mildly gratifying to look at, it would take much more inspiring subject matter to make worthwhile photos.

Just past the last toll booth, we branch onto a road leading eastward, the road suddenly lined with trucks and wall-to-wall traffic, a surprise coming from the virtually empty highway heading north. Large commercial estates and factories line the road, people streaming from the work establishments at the end of the work day. And already we are pulling into the bus station, Pullman buses ringing hangar-like buildings, our own bus continuing to the far end of the complex into one of the narrow bays, where passengers are expected to descend before the bus parks in finality somewhere else in the complex.

As an easily identifiable foreigner, I am predictably stalked by a congenial middle-aged man who mentions that he is a taxi driver and would happily drive me into the city centre. ‘How much?’ I ask him tersely. ’15,000 kyat’ he responds easily. I pat him on the shoulders and confide that he would do a better job trying to rip off someone else, sling my packs on my back and then stride through the entrance towards the remaining bank of taxis, the odd drivers calling to me. As per the American’s advice, I head towards the main road we entered from. It would seem far with all these packs, but I really could use a walk of any sort after being locked in the bus all day.

A few taxis slow down as I stride past the morass of cars and taxis, asking me where I am heading but then quickly speeding off before I have time to respond. At the main road, one of the men seated on their motorcycles asks me where I am going. ‘The city centre? Bus number 43 – it passes right by here’ he waves towards the main road. There you go – with marginal perseverance you prevail. But there is another problem – what look like city buses only display numbers in Burmese.

I turn to some of the local people loitering along the road, one man quickly pointing me to an oncoming bus – ‘that is the 43!’, the bus careening past and not stopping for some distance, being waved on by the traffic police, who in turn wave me in the direction of the bus, but I really don’t want to run all the way. Well before I reach the bus, a cab passes by me, the driver’s betel-soaked mouth leaning out the window and asking me where I am heading to. ‘7,000’ he offers to the city centre, which I decline – too much. ‘6,000?’ Too much – it should be 5,000, throwing out the unknown simply to see if it gains traction.

He refuses, pulls ahead, then slows down, waving to me again in agreement. I open his car doors, throw my packs into his utilitarian vehicle, and we are off into the seething traffic and stifling air pollution. And the traffic really is unbelievable, the slender Indo-Burmese driver manically thrusting his car into the precarious gaps between cars as I grip the car door and seat in mild panic, the obliterating smog not helping. And yet he is also gracious with cars seeking to turn clumsily in heavy traffic, deliberately slowing down and stopping to accommodate them. The traffic is hair-raising, and the city we drive through anything but inspiring, just a morass of dilapidated workshops, private residences on dusty lots, the air pollution utterly dismaying.

Eventually more modern structures appear, larger retail establishments, hotels, and around Inya Lake, car dealerships, condominium towers and luxury hotels whose size and apparent pedigree run entirely against the grain of everything we have seen thus far. Not to mention that we have been driving for some time, and even broaching the opulent Marina hotel at Inya Lake, we are nowhere near the city.

This is not the Yangon I recall, a slow-moving city resonant in magic, whose solemn visual cadence was interleaved with the sound of gongs and hypnotic music. An architecture of wealth and consumption gives way for even far greater indulgences further into the town centre, to the point that it seems utterly unlikely that this extravaganza can have manifested in the short last few years following the country’s detente.

With still some way to go, the idea of trying to see the city over the span of a few days seems improbable, as does the idea of trying to stay here and spend a minimum of money. The enormous sprawl of the city and the mass of people on the roads contrasts starkly with the complete emptiness of the landscape to the north of Yangon.

The Chan Myaye pension in side street just off the Maha Bandoola street traversing the core of Yangon houses a number of modest budget pensions on upper floors, tiny all-inclusive and well-maintained rooms at a modest price, although it would be difficult to get too excited about this kind of facility in the end effect. An old television and unplugged refrigerator are squeezed next to the single bed, a functionally sized bathroom adjacent, small windows peering out onto the narrow hallway, a chair and desk overshadowed by a shelf, a clothing rack and air conditioning unit on the far wall. The room may be relatively miniscule, but they have definitely done their best to squeeze as much as possible into the room, not to forget shelving and racks for hanging belongings, which many budget hotels amazingly manage to not bother with.

Emerging from the alley on which the pension is set, Maha Bandoola triggers a very vague recollection of walking the streets of Yangon in the day, but it is all very remote still, having been 18 years back. The city certainly seems far busier and concentrated than I remember, especially at this time of evening.

Maha Bandoola street bifurcates the centre of the old city along an east/west axis, the Irrawaddy river running just to the south. This would have been my base of operations some 18 years ago in my infant stages of Asia travel.

The eastern confines where the Chan Myaye guesthouse is located is more Indian and Moslem in nature, although further to the west, the centre is more Chinese. I just have to stop off in the first coffee shop en route to the Sula pagoda, not that this time of evening is right for drinking coffee, but what the heck, I have been deprived.

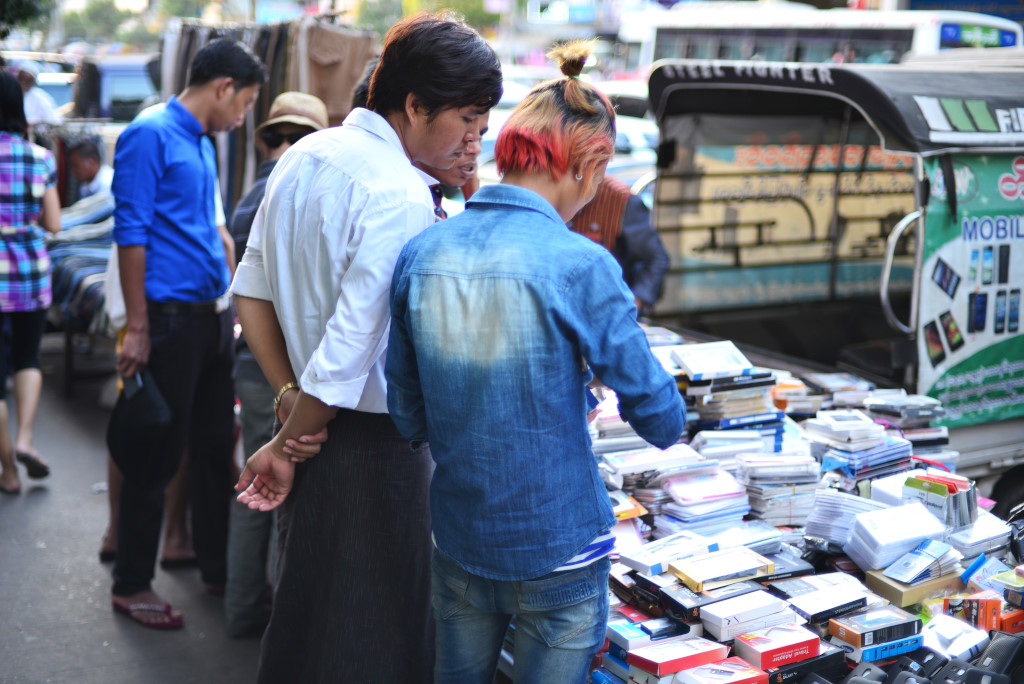

The Chinatown market erupts with every manner of produce and prepared food, although of course it is more of the usual, featuring boiled and grilled corn, grilled surimi in all shapes and sizes, some cold drinks, durian, apples, oranges, pineapple, avocado, apples, parathas, and so on. Alluring are the giant prawns and lobster, and for once I am thinking of not going cheap with the food, although most stalls have perhaps a single table to sit at, and they are all occupied.

It is a pleasure to take this vibrant panoply of life in with the largely Chinese clientele as well as the occasional self-satisfied young European couples. Most of the locals pay little attention to the foreigners, although I do get looks from time to time.

The architecture visible at night seems a lot more modern and better kempt than I remember, and I also remember a lot of arcaded passages which I don’t see at all here. I am actually taken by the amount of modernistic neon signs in Burmese, the lettering of which just seems hypnotic at night.

In this urban morass I see no temples, Shwedagon pagoda being nowhere in sight. Apparently substantial admission is being charged to the important pagodas in Yangon, which seems somewhat problematic, considering that you wouldn’t be compelled to visit because of their unique architecture, as they are essentially all the same in style, and not for their sacred quality, as that is at best relevant to believers, nor for the age, as they have all been completely rebuilt.

Reluctantly, I weave back to Bogyoke Aung San road, leading back in the direction of the Indian neighborhood my guesthouse is located in. Much of what I see in this area is simply uninspiring in terms of food, and I certainly don’t want to subject myself to the dregs of roadside hin booths. I see a number of Indian sit-down eateries that basically serve hins vaguely masquerading as Indian – no thanks!

The Nilar Biryani is an exception, with a variety of a la carte Indian veg and non veg dishes. And seated in the upstairs AC area, I am actually surprised how incredibly good the food is – now I really got my appetite back!