February 20, 2025

The Espresso Corretto in a pocket to the northwest of Santiago’s historic centre bordered on the far side by the river seems promising, but is in fact a small outlet in a big box luxury homewares store, hardly the kind of environment I had been thinking of in my quest to discover the secrets of Santiago. Given the enormous footprint of the store, the neighborhood running toward the river couldn’t be that interesting, either.

On the other side, however, toward the town centre, is a huge structure from which the newly built cable car runs, the grounds of the structure still somewhat disheveled, but the cable cars definitely in operation, judging from the continuous flow of the small modules suspended from the cable above, bobbing whimsically into the distance.

The cable car system only includes some four stations thus far, extending from just west of Parque Duarte, the heart of Santiago, into the southwestern quadrant of the small city. Based on the enormous concrete pylons being erected along the northern periphery of the old city, the system will be extended to the northeast as well.

Judging by the locals’ obsession with cars, the fact that there is simply not such a big supporting population, and tourists barely come here – I have seen no Caucasians in Santiago since having arrived – I am not sure who is intended to use this system. Apparently, in rush hour, it is busy, but now, in the early afternoon, perhaps only a handful of passengers are visible at each station.

Taking a cable car into the extended suburbs of Santiago is hardly what I expected to be doing today, but there it is, the rolling green landscape speckled with modest housing settlements below, shotgun shacks slowly being converted to solid brick-and-mortar structures as the respective families presumably acquire enough money to improve their lot.

What seems incredible is not just the tremendous financial outlay to create this sophisticated, edgy take on public transportation, but the evidently incongruous fit, the system built – or rather, in the process of being built – for an urban environment that simply doesn’t have an enormous footprint in terms of population and wealth. Barely a fraction of the cost of maintenance, the power consumption, and the plethora of staff at each station, security, attendants, cashiers, and maintenance personnel could be covered by the DOP 35 (ca. CAD .75) fare, given the few passengers in the system, never mind the capital costs.

The views of the town from the lofty cable car are of course spectacular, several monuments standing out, the towers of the cathedral on Parque Duarte on one side of the ciudad colonial and the Monumento a los Héroes de la Restauración on the east side. Much of the rest of Santiago de los Caballeros is relatively unimpressive, but that also means that from a street level, it will be pleasant and relaxed, given how spread out it is. While the town is on relatively uneven terrain, it is set in a broad valley, with a low ridge of mountains visible in the distance that separates Santiago from the north coast of Hispaniola island.

The second last station from the top, Emiliano Tardif, is a few convenient blocks from the Parque Duarte, the main square of the town, lined with its local vendors of snacks, empanadas, lottery tickets, cell phone covers, and other small, inconsequential items that allow people of very modest means to survive in some fashion. There are people who go about their business on the square, but most would have little money to spend; there are certainly no tourists.

The towers of the cathedral look impressive, but judging by the polished interior, the church is relatively modern, certainly much newer than the foundation of the new city in the mid-16th century, when the original city was destroyed by a devastating earthquake.

Excerpted from Wikipedia: “Founded in 1495 during the first wave of European settlement in the New World, Santiago today is one of the Dominican Republic’s cultural, political, industrial and financial centers. Due to its location in the fertile Cibao Valley, it has a robust agricultural sector and is a leading exporter of rum, textiles, and cigars. Santiago is the second-largest city in the Dominican Republic, the fourth-largest city in the Caribbean by population, the largest Caribbean city that is not a capital city, and also the largest non-coastal metropolis in the Caribbean islands (Wikipedia).”

Unlike the immediate vicinity of the cathedral, the streets of Santiago’s historic district are far from memorable, although as I have already seen yesterday, the town seems to be littered with sporadically distinctive moments, modest but impeccable Creole houses, pretty squares, alongside uglier, run-down modern structures, and in some pockets, such as around the cathedral, disconsolate ambulatory vendors plying their limited selections of clothing and other textile wares, socks, shirts, underwear, and so on.

The agglomeration of vendors doesn’t line the narrow, poorly-maintained sidewalks due to the presence of the temple of faith, rather, the adjacent Mercado Modelo; vending from the street presumably avoids having to pay any fees for market stalls. A few blocks to the east lie smarter small department stores and other retail establishments, and of course, the French-owned traditional buffet that offers an apropos view into tasty and filling Dominican fare, at a nominal price.

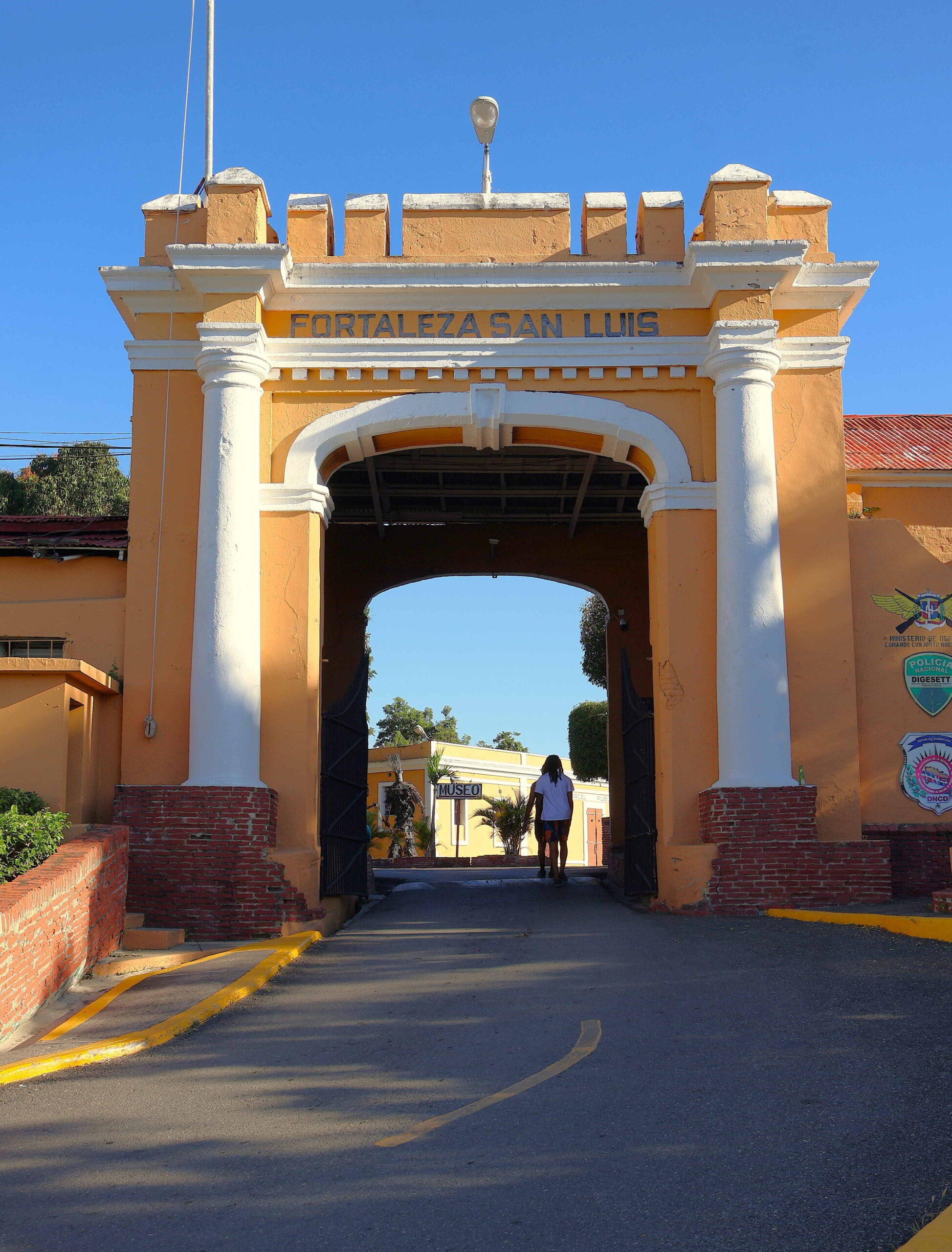

The Fortaleza San Luis is a stolid affair, a broad, walled-in concourse raised perhaps 5 metres above street level, the city on one side, the Yaque river on the other. A square, pastel lemon-toned clocktower announces the presence of the historic defensive fortification, featuring squat porthole windows and a crenellated tower. There is one access road, leading from the edge of the colonial city.

The fortress was built in the mid-19th century when the country regained its independence from Haiti, was used to garrison Spanish troops when the country was returned into Spain’s fold, and by the national military in the battle to reclaim the country from Spain again. The contemporary grounds of the fortress are dedicated to various police and military outfits, and the public is free to wander around the grounds, largely devoted to parking, although there are fanciful stone and metal sculptures littered across the grounds, perhaps in connection to the museum and cultural agencies that are present on the site. Here, as is the case with the rest of the town as well, there are no other tourists to be seen.

I am overcome by exhaustion, far more tired than I should be. Looking back on the day, the culprit is the fact that the owner of the apartment I am staying in didn’t replace the drinking water canister, which means I have to buy bottled water, and in turn don’t have enough to fill smaller bottles to carry with me. So I have unwittingly been rehydrating by drinking pop during the day, which is really not good. I should really boil water at the apartment and refill bottles, but befitting the weathered state of the apartment, the pots and pans in the kitchen simply look too filthy to boil water for drinking.

Rounding out the day with a trip to the Centro Cultural Eduardo León Jimenes is a possibility, but I am simply not feeling very motivated, and from the photos I see on the web, this may be a anthropological museum with substantial content, in another words, not just a locale to breeze through and pay minimal attention to the displays. So perhaps another day – or not at all. On the other hand, if the exhibition focuses on the indigenous Taino culture, it may be the only opportunity in the country to take this kind of thing in.

The remaining option is to return through the now abandoned streets of the historic district to the monument on the east side of the centre for the remaining light of the afternoon; once the businesses close in this area, it feels grim and uninviting, and the assorted police and private security forces do little to welcome the few visitors to the pathways circling the monument, presumably due to the paranoia surrounding the tobacco company-funded private event taking place on the stages at the pinnacle later on in the evening.

The degree of security seems as preposterous as my desire to even be here, hence I am off again to the southeastern quadrant of town where my Airbnb is located, past the gleaming neon lights of the retail establishments and restaurants catering to a far more prosperous clientele than would be found in the barrios above which the cars of the teleférico sway. Next to the Supermercado Olímpico, small but clean and amply-provisioned eateries offering local culinary staples, ice cream, and snacks, showing that to eat well you never need to wander far from home in Latin America …