February 4, 2025

Light streams into the rooms of my modest apartment in the Condominios Santa Lucia on the western fringes of the historic district of Santa Ana. I cobble together a breakfast in the usual fashion from my acquisitions from Selectos and various street vendors. A morning of writing ensues, something that would best occur in the evening, except that the apartment is too hot in the evening, making it difficult to focus on writing. Of course, it delays embarking on the day’s plans …

Time to finally leave my middling abode; happily, the neighborhood is relatively calm in the morning. Given the amount of housing that seems virtually abandoned in the area, it surprises me that there are so few Airbnbs available closer to the centre. Perhaps the abandoned housing is a legacy of the era of insecurity, while the demand for temporary housing is a result of tourism having jumped so much in recent years. I am later told that the country also suffers an acute housing shortage – so much for Airbnb.

Today I will visit the Parque Arqueológico San Andrés, which is the other one of the two ancient Mayan sites that lie between San Salvador and Santa Ana. I pick up some chicharrón pupusas from a stand by the Parque Santa Lucia, and they are unbelievably good; herbal, fragrant, far better than anything I could have imagined. I

n the vicinity of the park, there are elegant colonial-style villas, surprising for the otherwise down-to-earth area. I stop to chat with a woman entering the courtyard of one particularly fine specimen; she tells me that it is a family dwelling, and that she has returned a year ago from a three-year stint in in Rome. They currently use the home to provide a combination of child care centre and preschool. Apparently, much of the area seems abandoned because many people moved to San Salvador for work, due to limited economic possibilities locally, and may only return on weekends. I nonetheless wonder how much of their departure has to do with instability, how safe the town was prior to Bukele assuming control of the country.

Since the Ban Ban bakery is en route to the main road, why not stop off for a quick espresso! The establishment is not so busy, nor for that matter the sidewalk of the road leading to what appears to be a more commercial area to the south of the centre, with shops lining the street, the sidewalks cluttered with improvised shops, food stands, and ambulatory vendors. Given how filling the pupusas I have been eating are, there is no way I can afford to indulge in more street food, although by the looks of what I see in the buffet trays laid out with colourful meat preparations, sauces and starch dishes, there is a lot more potentially very tasty fare to take in.

The TUDO bus station is a staid affair, and the local bus to San Salvador leaves with only myself as passenger. The coach stops regularly in the cluttered traffic of suburban Santa Ana to pick up passengers as well as throngs of ambulatory vendors selling spiced and sweet peanuts, sandwiches, chicharron, tamales, French Fries, drinks, and so. Not out of hunger but curiosity and a desire to support the vendors, I buy some sandwiches, and am again surprised by the quality of the food – the slices of soft white bread are filled with slightly herbed chicken salad, the texture slightly creamy, with no gristle, and a touch of green, subtle and very good.

Despite having clearly told the driver several times that I want to get off at the Parque Arqueológico San Andrés, the driver breezes by the entrance, then disclaims even knowing that the place exists. Thanks to my usual skepticism and more importantly, Google Maps, I manage to disembark not too much beyond the entrance of the park. From the gate, a trail arcs for several hundred metres around the terrain until the entrance of the historic complex, with a ticket office, parking area, heavy, block-like buildings for facilities, cafeteria, and most importantly, a museum, similar to the organization of the Parque Arqueológico Joya de Cerén.

Judging from the few people I see milling around the services and the almost empty parking lot, there are few visitors, but they are all foreigners. In a series of rooms with identical vitrines containing information placards and a variety of finds from the site, mostly ceramics, the museum navigates the history of San Andrés, its chronology, and the nature of the culture that was discovered here by means of descriptions of the architecture, the layout of the ceremonial centre, and the human finds from the site. The site and culture is labeled Maya, although it doesn’t necessarily have clear visual associations with what I perceive to be the early Mayan culture.

Along the lines of 280 archaeological sites have been found in the Zapotitan valley where San Andrés is located. San Andrés reached its apogee in the late classical period, 600 – 900 A.D. As much as the environment provided fertile ground for the ancient Mayan societies to evolve, the volcanoes surrounding the valley, including Ilopango, Loma Caldera, San Salvador and El Playón have had a significant impact on the geography, settlements, and agriculture.

The eruption of Ilopango around 450 A.D. destroyed much of the environs, while Loma Caldera buried the village of Joya de Cerén around 600 A.D.; however, the volcanic ash has also been tremendously beneficial for the soil. Following its destruction, San Andrés was occupied by other groups, then during the colonial period, by friars of the Dominican order, who used the locale to produce indigo, until an eruption of El Playón entirely buried the site.

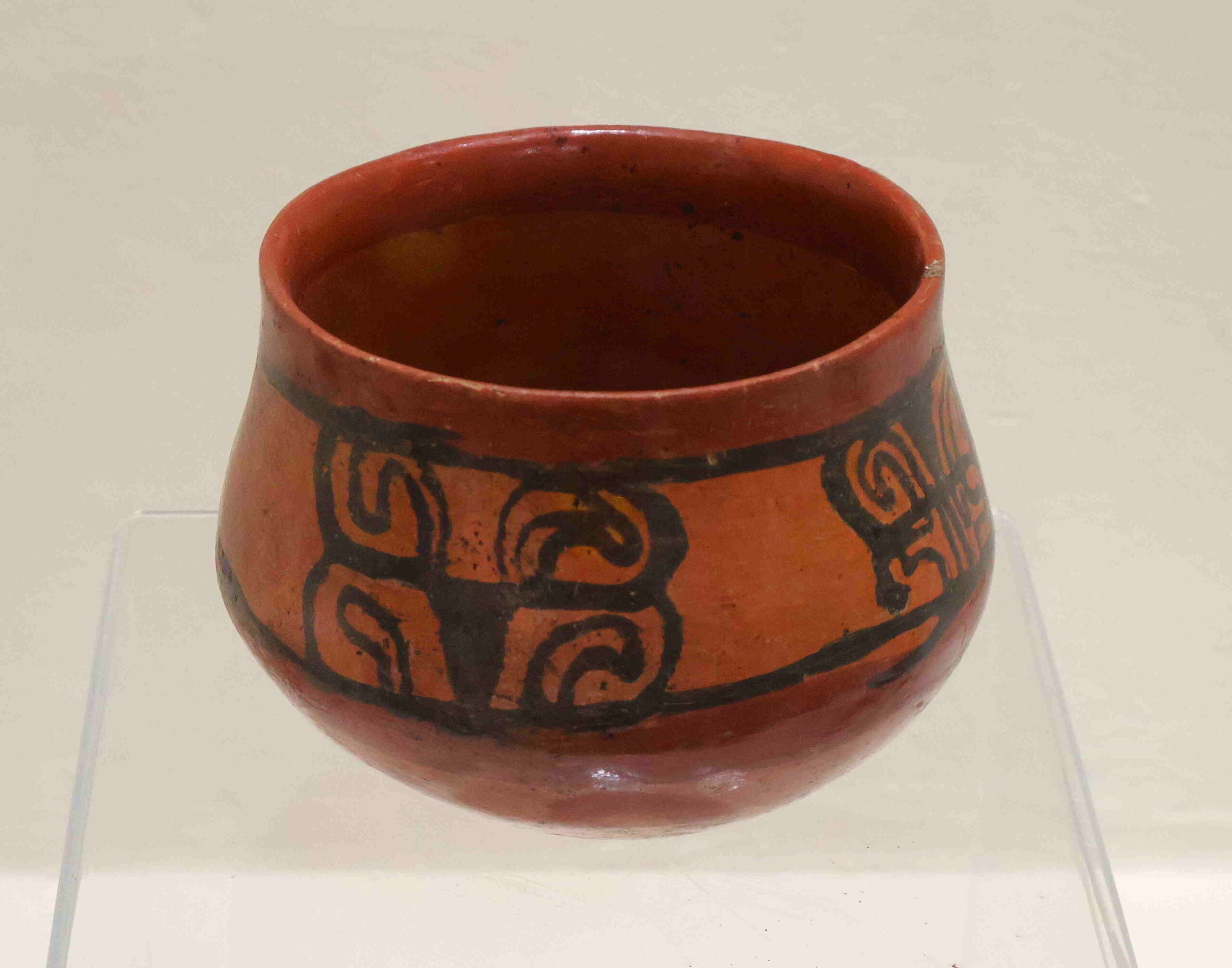

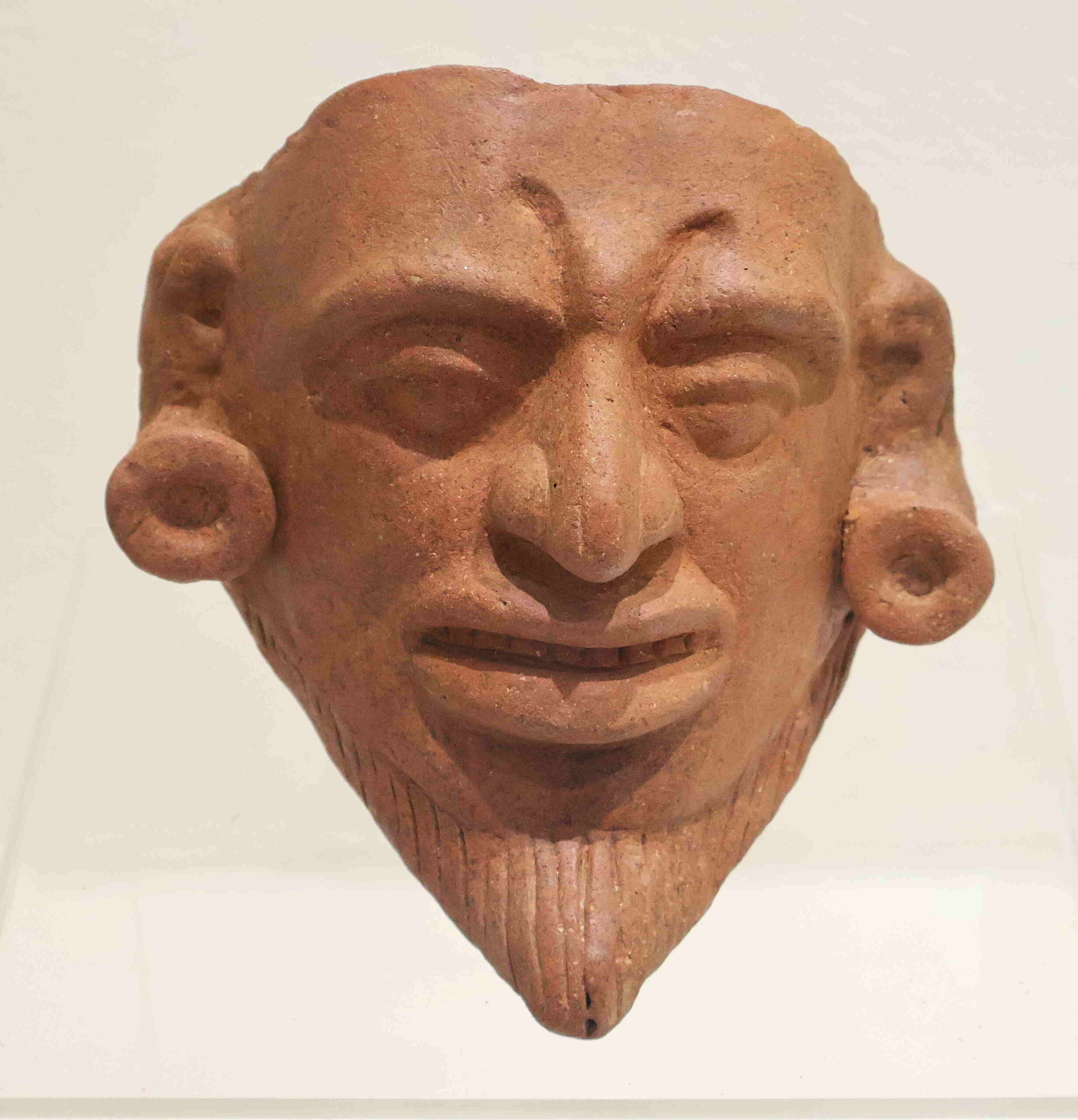

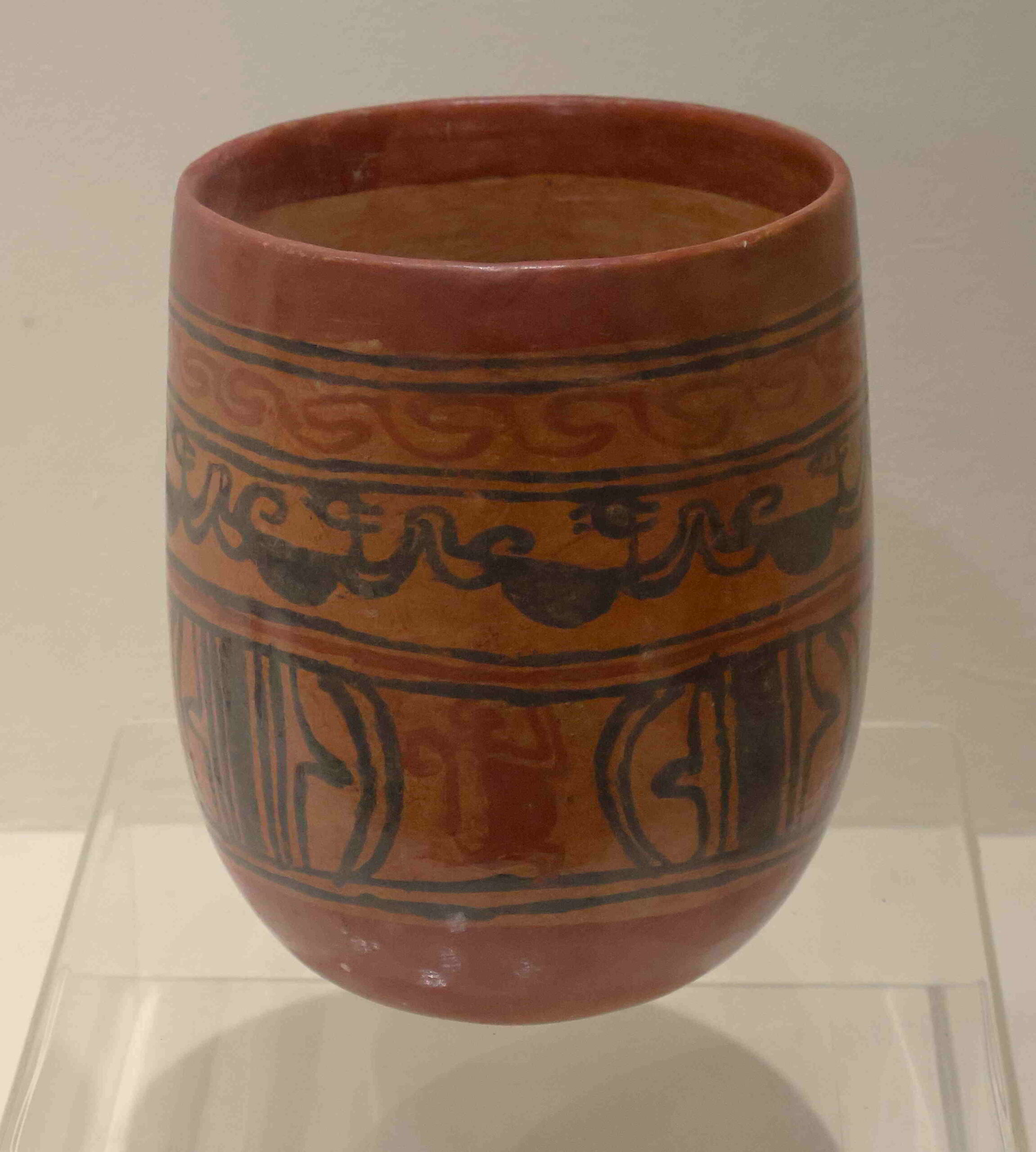

The artifacts in the museum relate to various aspects of contemporary technology, domestic needs, and the pursuit of faith, often heavily degraded, and assume fantastical, grotesque shapes. Ceramic bowls dominate the exhibits, often simple in shape, the mouth narrower than the body of the vessel, adorned with simple, flowing symmetrical patterns in a variety of earth tones, the pale background of the images subjected to evanescent colour washes. The dishes seem crude and archaic in their aesthetics, and yet upon closer inspections speak to an alluring degree of refinement.

From a plaque in the museum: “The pottery found in San Andrés reveals that there was a local production of ceramics and also ceramics imported from other Mayan sites. Within local production, there are Campana ceramics composed of plates with supports, decorated in black, yellow and orange, as well as the Scrapped Slip type of pottery, used for storage, processing food, and as eating implements. The imported pottery was mainly of the Copador and Salua types. Copador ceramics include vases, plates, and bowls, and are polychromatic, and decorated with hematite as well as animal and human figures. The Salua ceramics were used exclusively for ceremonial use, include vases and bowls, and are decorated with images of jaguars and humans in elaborate costumes, partaking in ceremonies, depicted with polychromatic decorations in orange and black.”

While Joya de Cerén consists of what were relatively mundane wattle and daub buildings that were buried under a heavy layer of volcanic ash, San Andrés is a ceremonial centre consisting of a series of ziggurat-style pyramids, raised platforms, and courtyards, much of the original site restored, and virtually the entire complex covered with a blanket of cropped grass.

Individual structures are labeled very simply as “Structure 1” or “Structure 2”, hardly very imaginative, but then there is little to trigger the imagination here, other than the relatively bucolic and peaceful nature of the environment, the mature trees whose canopy of green envelopes the place. The structures feature no embellishments, at least not on the accessible portions of the structures visible to visitors.

Sightlines are quite magical, every coordinate on the site offering another unique view of the manicured structures, surrounding forest, and dramatic blue sky. Only a few visitors are apparent here, and for the backpackers making their way through Central America, it is already quite surprising to have made it so far afield, as they typically wouldn’t spend that much time in an individual country; in El Salvador, they focus on the beaches, which is precisely where the two young Lithuanian woman I meet lying on the grass have spent their time in the country.

The environment offers a tranquil and introspective departure from the quotidian bustle of the polluted and chaotic urban environments in the country, the meticulously cropped lawn swooping up to gentle hillocks as well as excavated pyramids, their rigorous geometry contrasting starkly with the flowing lines of the surrounding nature, and above, the brilliant cerulean sky punctuated with splashes of pure white cumulus puffs …

It is already 4 pm, but it seems that there is far less bus service to Santa Ana than I would have expected. Or perhaps there is something else at play. Workers begin leaving the gates of the archaeological site, one of whom tells me to stand at the bus stop, where I will be joined by other workers going home for the day. Only two women approach while most workers leave by means of their own vehicles; one of them explains that I need to wait for the 201 bus to Santa Ana.

It seems that most of the coaches passing by either don’t stop here or are heading somewhere else, which seems unusual, given that Santa Ana is by far the largest town to the north. Well, at least the 201 that does finally stop has empty seats that are clean, with new plush, in stark contrast to the standing room-only minibuses.

I can relax on the trip back to Santa Ana, although due to the late hour, I will again be prevented from taking on any other activity, specifically, visiting any of the hot springs to the east of the centre. While the core of Santa Ana is limited to smaller, family-style businesses and ambulatory vendors, much of the retail space to the south of Santa Ana is dedicated to American big box chain stores and restaurants, spread out on sprawling properties.

I was uncertain as to how close to the centre the bus may proceed, but at one stop, a young woman informs me that I need to dismount, given that the bus is continuing to Metapan, far to the north, where the borders of Guatemala, Honduras, and El Salvador meet. To continue to the centre, I can take the 8, she tells me: it certainly is too far to walk to Plaza Libertad, and I couldn’t imagine a more productive way of spending 25¢ on bus fare.

Bus travel certainly is far from stressful in El Salvador; I follow the journey toward the centre on my map, but at a certain point decide to dismount: there is still enough light, and the gently undulating topography, the river of multi-coloured adobe tenements hugging the narrow roads, and the golden hues of the low hills just outside of town create ideal photographic subject matter. A young woman tells me that we are on the street where the final push came in the last days of the civil war, and that perhaps because of what people saw here, they were happy to move to San Salvador and only occasionally return.

The east side of Santa Ana is somewhat grotty, but nonetheless rich in character, the low surrounding hills shimmering in golden earth tones, and closer to the main square, the twin white towers of the cathedral are visible. The typically whitewashed adobe houses are rich in modest architectural detail, although the boldly-emblazoned FMLN sign on one in particular captures my attention, its portal open and interior ablaze in light as a man sweeps its floor. The decor in the utilitarian space is limited to red banners and images of Oscar Romero, Fidel Castro, and Che Guevara.

The man tells me he was 15 when he joined the FMLN as a foot soldier in the mid-1980s; in the day he was a key party member, and had been sent to Russia, Cuba, and Vietnam on missions. In earlier years of the conflict, fighting was in the remote countryside, whereas toward the end of the conflict it moved towards the cities. He tells me that following the decade of implementing progressive social policies in the country, FMLN supporters had the audacity of supporting the likes of Bukele. It certainly says volumes about ingratitude – perhaps they simply took all the work that the party had done for them for granted. But perhaps they were also fed up with the extent to which the gangs had held the country hostage, not something that anyone in opposition wants to give due credence to.

He can’t believe the reversal the country has experienced under Bukele; he tells me that Bukele has been in power for several years now, but in fact, he had already ruled one term, had the constitutional court effectively overthrown and replaced with his loyalists to allow him to run a second term, which he was reelected to in a landslide last year. He has closed 29 schools in the country; it is believed that the money Bukele saved from closing these schools and slashing social equity programs has funded his lavish private property acquisitions. And despite denying it, people in the country have been disappearing and being killed.

The competing ARENA (right) and FMLN (left) parties are in shambles, both contending with reputations for being ineffective, corrupt, and allowing the extreme levels of gang violence El Salvador was notorious for, which under Bukele’s harsh response has virtually disappeared. The back story to our conversation is the current meeting of the newly-minted American Secretary of State Rubio with Bukele in San Salvador to discuss shipping criminals from the United States to El Salvador in exchange for payment. Conservatives love incarceration – but it’s expensive – and El Salvador is a far cheaper and more ruthless place to unload undesirables.

Even prior to Bukele’s dismantling of the markers of social progress, there was still a lot to improve in the country. While urban areas enjoy full access to infrastructure, rural areas often have no services, no electricity, and no schools. It doesn’t help that locals may not even bother sending their children to school, given that the primary value of the children is as labour. And for the 29 schools that Bukele has shuttered in the country – where has the money saved gone to?

Initially motivated by the desire to take a photo of the FMLN banners, I spend far too much time immersed in a political conversation with the man in the office; I continually make motions to leave, but then another enticing subject presents itself. I wonder to what extent it is even safe for me to expound about radical politics in full volume in such a public location, given the ruthless reputation of the current regime.

By the time I finally leave, it is dark outside, so I definitely won’t be taking more photos. However, Santa Ana in the evening is rich in atmosphere. And – thanks to the current regime – now safe to walk through, irrespective of where or the time of day. Thinking of the cafe the woman had told me about earlier on in the day, I meander along the barely illuminated streets that ring the cathedral, but while I see a few restaurants and bars, mostly with a somewhat noir charm, and largely bereft of customers, I doubt that the coffee shop in question even exists.

Given that I am returning through the darkened alleys of west Santa Ana on foot, I may as well go several blocks out of my way to the Pupuseria Madrid that the owner of my apartment raved about. In the end, pupusas are only so interesting, but to make them in the proper rustic, artisanal manner is very time-consuming and also imbues the finished product with subtle characteristics of the corn masa elaborated by hand.

The Pupuseria Madrid is open but empty – apparently, they have guests primarily on the weekend, when locals return from San Salvador to Santa Ana, but now, mid-week, there is little business, a reflection of how moribund the neighborhood is. But the location is utterly atmospheric, and it is nice just to stare off into the distance of the tree-lined abandoned streets, the outlines of the traditional adobe structures barely visible in the faint nocturnal lighting.

I opt for pupusas that I would not be familiar with, mora, a bitter leaf that the young women showed me the other day, with a spinach-like flavour, ayote, or squash, which seems have a very mild flavour profile, and carrot, each pupusa also made with the soft white cheese. What renders the flavour profiles even more interesting is the shredded cabbage condiment marinated in vinegar that is also slightly hot, yielding interesting blends of bland, sour, and bitter, on a backdrop of the creamy melted white cheese and grilled masa of the pupusa shell.