February 2, 2025

According the ATM Fee Saver app I downloaded, there are several banks in the area whose ATMs disburse money on relatively optimal terms: I need only walk up to Calle Montserrat, then head west past the traffic circle onto Boulevard Los Proceros. Walking through the immediate neighborhood is easy enough, but to traverse what amounts to a larger traffic interchange, I need to climb over a series of overpasses. Normally, that would be an entirely regrettable affair, but in this locale it turns out to be quite an artistic excursion, the materials used for structures, the design, and accompanying art installations rendering the experience quite memorable. Stylized colourful murals and mosaics adorn the ramparts of roadway structures and free-standing sculptures with scenes blending tradition and modernity, the coloration contrasting vividly with the colours assigned to the structural elements of the interchange.

Apparently, in the small shopping complex immediately to the west of the traffic interchange, there is a Bank of Nova Scotia, which, according to what I read on the net, charges no commissions on ATM withdrawals. And yet, navigating the shopping plazas on either side of the road, it turns out there is no such bank. A woman seated on a staircase of the building where the bank was to have been located tells me that there used to be a Scotiabank, but it closed years ago. Further to the west along the highway, there is a Banco Cuscatlán with an ATM – irrespective of their commissions, they at least apparently have higher withdrawal limits than the trivial amounts set by many banks on ATM withdrawals in the country.

I trudge along the highway, then closer to the bank realize that there is no way I could safely cross the highway, and so need to make my way even further to the west to use the overpass, which I clamber over, then approaching the Cuscatlán outlet, realize that it is entirely shuttered, something that is of course again not reflected on the Google Map.

My frustration mounts at the realization of how unreliable Google Maps is – this will certainly impede running errands on my trip, given the experiences I have made in the past. As a compromise, I take an Uber moto to the Super Selectos on the north-south boulevard to the immediate west of Terminal de Buses de Occidente, where the ATM works and allows me to withdraw a reasonable amount of money – despite the high commission – then with two bottles of cold, sugary beverage in hand, I am finally on way to the bus station to catch a bus in the direction of Santa Ana.

Having now wasted enough time trying to get money out of ATMs, I am set to visit the archaeological sites close to San Salvador. Given that it is almost 2 pm and it gets dark around 6 pm, I am hardly very hopeful about seeing both the Parque Arqueológico Joya de Cerén and the Parque Arqueológico San Andrés, especially given that I would have to backtrack a considerable distance from the former to get to the road leading to the latter. The reality of traveling is so often marred by ludicrous errands and minutiae that you constantly have to keep track of. But at least once the debacle with finding the appropriate ATM to withdraw money from is out of the way, I can make my way to the bus station – albeit a wearying trudge in the heat on foot – and once there, the chicken bus to Opico – which can drop me off at the Parque Arqueológico Joya de Cerén – is already waiting for me.

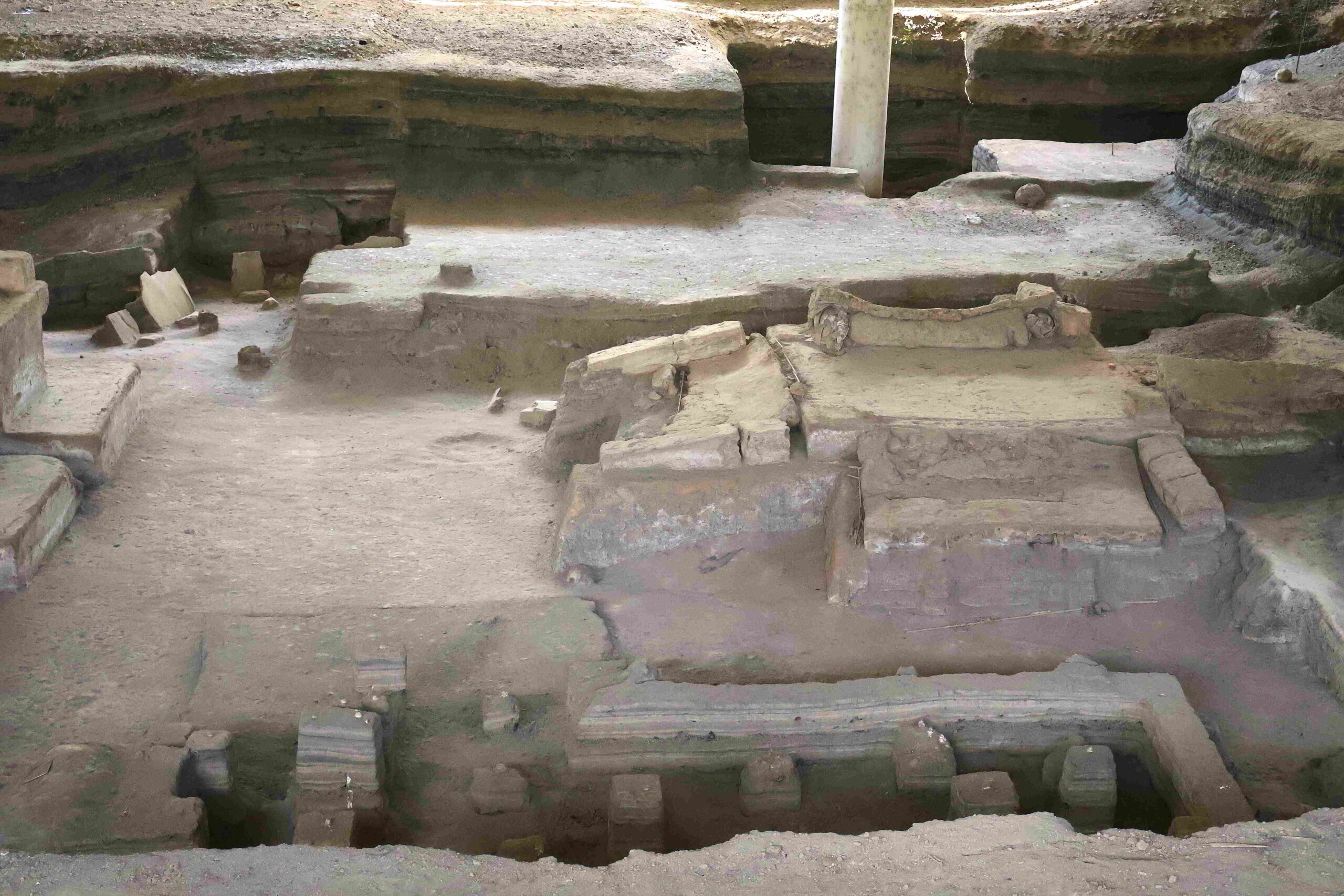

The Parque Arqueológico Joya de Cerén is not particularly large, much of its terrain dedicated to the entrance gate, parking, and walkways surrounding the covered excavations. A paved walkway leads the visitor around the perimeter of the pits from which the site has been excavated, the lot covered by an enormous canopy, the pits characterized by fragmentary structures erected against a backdrop of dark substrate. The railing separating the walkway is punctuated by occasional plaques that explain the remains of the structures below.

“Joya de Cerén contains the remains of a pre-Hispanic farming village that was covered by a volcanic eruption in the seventh century AD. Around AD 500, the central and western parts of the territory of El Salvador were buried beneath thick layers of volcanic ash from the Ilopango volcano. The area was abandoned until the ash layer had weathered into fertile soil and the Joya de Cerén settlement was founded. Not long afterwards, it was destroyed by the eruption of the Loma Caldera. The circumstances of the volcanic event led to the remarkable preservation of architecture and the artefacts of ancient inhabitants in their original positions of storage and use, forming a time capsule of unprecedented scientific value that can be appreciated in present times.

Underneath the layers of volcanic ash, the best preserved example of a pre-hispanic village in Mesoamerica can be found, with architectural remains, grouped into compounds that include civic, religious and household buildings. To date, a total of 18 structures have been identified and 10 have been completely or partially excavated. All structures are made of earth and important features like thatch roofs and artefacts found in-situ have been recovered.

The excavated structures include a large community (public) building on the side of a plaza, two houses of habitation that were part of domiciles, three storehouses (one was in the process of being remodeled), one kitchen, and a sweat bath. On the northeast side of the plaza there is a religious building devoted to communal festivities and one where a shaman practiced. Rammed earth construction was used for the public buildings and the sauna, and wattle and daub (which is highly earthquake resistant) for household structures.” (Excerpted from whc.unesco.org/en/list/675.)

The Casa de Reuniones is unusual, in that the exposed building consists of smooth, solid stone walls arranged in a rectilinear pattern with well-formed square windows, which suggests that much of the structure may have been reconstructed. Adjacent, a storage area built of wattle and daub containing various vessels, seeds, and cloth, used to process agave to produce fiber. The remains of the chamber are rudimentary, and dwarfed by the stepped layers of volcanic ash from which the original buildings have been excavated.

Further along, on the foundation of another cavity excavated according to a geometric profile from the deep bed of centuries of volcanic ash are fragmentary walls encasing the remains of a small dome that represents a temazcal, or place for purification, which is – according to archaeologists – in an extraordinary state of conservation. The structure was essentially used to perform steam baths for the purification of the body and spirit, whereby the stones housed at the centre of the building’s floor would be heated and doused with a herbal liquid.

There are more oblique structural remains, difficult to make much visual sense of for the retail visitor, but nonetheless archaeologically significant, including a kitchen space and a ramshackle affair that archaeologists deemed was a shaman’s house inasmuch as they found artifacts used for divination. Outside, a different spectacle awaits, a collection of well-tended trees and shrubs, intended to represent the crops local pre-Colombian peoples would have drawn from to support their existence. They are of a culinary and functional nature, the former including corn, manioc, and cocoa, and the latter agave and tule for providing fibres for making rope, mats, and baskets.

Outside the archaeological site, there are shacks selling snacks and prepared foods in the area of the bus stop, which abuts a T-intersection leading to the contemporary village of Joya de Cerén. I wouldn’t mind getting something to eat, but everything seems closed – except the enclosed area without signage from which the most fragrant odour emits, which has to be an eatery. And yes, they make pupusas, three for a dollar, of the squash ones, two for a dollar, a fraction of the price of the same fare offered in the capital city. Location, location, location!

Chatting with the two young women preparing the pupusas is instructive; they tell me of the variants on pupusas, this profoundly El Salvadorean fare, thick tortillas stuffed with some filling, nominally refried black beans and fresh white cheese, but they can also be filled with many other ingredients. The variations available relate to the locale and its associated produce as well as the season; the local culture does not determine the kinds of pupusas produced. One of the young women shows me a bowl with what seems to be a masa prepared with cheese and a fragrant herb of some sort, incredibly tasty and nuanced. Even the simple pupusas I taste here are redolent of flavour, the masa somewhat glutinous and chewy, the refried beans sublime and the cheese gooey but subtle.

As I wait for the food to be prepared, I see a constant stream of buses pass by the comedor, however, when I finally finish eating and move to the roadside, there seem to be no more buses. When a relatively full microbus arrives with the same driver who brought me to Joya de Cerén, an older passenger tells me that the bus service slows down considerably in the late afternoon, the last bus passing at 6 pm. It’s probably just as well that I didn’t continue to the Parque Arqueológico San Andrés, as I would risk not being able to return to San Salvador, at least not by public transport.

The journey back to San Salvador proceeds more quickly than the outbound journey, and happily, the same woman who I spoke with earlier insists I sit next to her when other passengers dismount. The late afternoon is radiant, the small communities passing by us, then Santa Tecla again, with its grid layout of charming, pastel-toned colonial architecture sliding by us, before we enter the fray of San Salvador with its broad highways, gleaming towers and sprawling shopping complexes.