February 5th, 2018

I wake up early this morning to another heavy fog. My room is filled with exhaust fumes, even though there seems to be no traffic on the street. The air pollution in Colombian towns is just out of control, particularly near the town centres, the streets perennially filled with commercial vehicles belching clouds of black smoke. I thought I would have a greater tolerance of the level of air pollution, but I am finding it to be very irritating. I can’t breathe properly, and am coughing and sneezing frequently. It could also be that the elevation is contributing to the impact on my body.

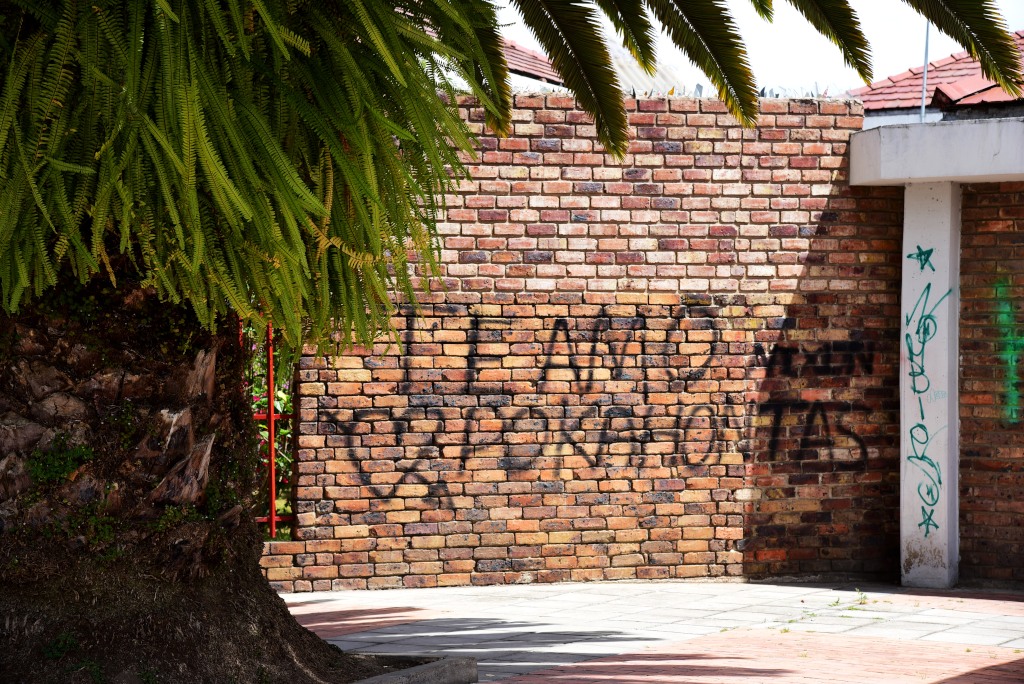

It occurs to me that I have not walked around the area behind the Plaza. Somewhat surprisingly, the area features a few interesting visuals, including a small plaza with mature trees, colourful murals, adobe and terracotta architecture, as well as views of the hill rising behind the town.

In the Spazio Caffè on the west side of the plaza, I get into a very long-winded conversation with the artistically-minded owner. Her customers appear to be local businesspeople and the elderly gentry. We discuss the subject of tourism and how it could be developed in the region, not that I have much qualification on the subject, other than having visited a few places in the country over the last few weeks.

Irrespective of the possibilities that the smaller, less-traveled spots may in theory offer, there are so many competing sites of interest, and the vast majority of visitors will be intent on visiting the premier attractions in the country over a relatively abbreviated time frame.

She loves painting, a copy of a Fra Angelico masterpiece she painted hanging on the wall. She certainly chose well! She beams at me appreciatively as I extoll the virtues of Italian Renaissance painting and the work of Beato Angelico himself. Her cultural leanings seem to go far beyond the apparent limits of her humble town, although the physical environment shouldn’t necessarily impose limits on the imagination of its citizens.

Her daughter lives in Pittsburgh, and is doing her PhD in Biology, her daughter’s husband his doctorate in Mathematics. They had previously lived in London and loved the culture; Pittsburg may have its cool factor, but it certainly is not London.

She is appalled that I was told that the Sogamoso museum was not worth going to, and insists that I go, as it is the most important archaeological exhibit pertaining to pre-Colombian indigenous culture in the country. The museum may not be taken seriously, however, since Sogamoso is a small and unimportant town. Moreover, the area the museum is located in is not dangerous, and is completely safe to walk to.

The upstairs gym the café owner has pointed out further down the block on Calle 11 is definitely a going concern, and seems to have all the right equipment. It will be open after 4, just in time for my return from the villages I plan on visiting today.

North on Carrera 11, the nighttime world I discovered yesterday evening reflects a unique sunwashed life in the growing heat. I look for interesting subjects, images that present amusing or interesting contrasts. The opportunities definitely arise between the students on the street, the architecture, the murals, flowers, and sculptures around me.

I am utterly fascinated by the incredible old Renaults on the street here, often restored in whimsical and beautiful ways.

Most of the eating establishments are pizza and burger joints, and look even less interesting during the day.

The highlight of the excursion is the modernist church the likes of which Colombians seem to have a predilection for. On the other hand, the park across the street may be expansive, but hardly very interesting.

I ask myself what the chance would be that buses to Mongui would pass by here. As luck would have it, this is exactly where they pass by, but not knowing so at this time of the day, I am still compelled to walk all the way to the bus station.

Where do these incredibly well-endowed women come from? That remark doesn’t apply to every woman I see in the street, but still, large quantities of them, impeccably turned out, and bursting at every seam …

The cafeteria San Valentin has just opened. Lunch consists of a soup, salad, roast chicken, rice, aji, all excellent, followed by a scoop of excellent mango ice cream, which is made in-house. This is definitely not an ordinary cocina tipica place. The place is clean and spacious, unlike much of the competition. It seems that the vampy owner keeps her robotically beaming employees under the gun, although she needn’t, as the food is impeccable.

The expansive square near the bus station had seemed like another space of no utility, but on closer inspection, holds its own unique drama. Hand-written aphorisms are posted on placards on the trees, which lends a sense of romance to the place. Overgrown weeds flower on the banks of the canal, shade-bearing trees running the length of the canal. The canal may carry no more than a trickle of water at the moment, but here as elsewhere there are always amazing murals on the walls. Then unexpectedly, a horse-drawn cart trots by.

The trip to Mongui begins with the usual meandering departure from the suburbs of Sogamoso, proceeding through the floor of a valley, then rising gradually into a spectacular landscape of green, the buseta weaving along the serpentine road as it climbs through the forest and pastureland higher and higher into the sky. The ubiquity of the eucalyptus trees is not inspiring, as their prevalence will preclude the ability of competing local vegetation to prevail. it seems the whole area had been deforested, then at some point it was decided to take the cheapest and easiest route to reforest.

Mongui is a town of green, featuring green doors and green sashes. Whatever the reason for the green theme, it certainly gives the town a unique imprimatur. Even the suburbs are characterized by many new developments, reflecting a town whose fortunes are on the upswing. The new housing complexes are being developed with the same aesthetic of white plaster, green doors and window frames, with occasional splashes of red.

The ostensible reason for visiting Mongui is that the town is starting point for the trek into the Páramo de Ocetá, which I will not be partaking in, due to lack of time in the near future, and the fact that I will be trekking in the similar but more impressive Cocuy mountains to the north later on.

The town flows along a hillside, offering dramatic views of the surrounding verdant hills around the town. On one side, the town drops off dramatically into a valley, and on the other, climbs steeply up a verdant hillside.

Here, as elsewhere in the region, the plaza is expansive, cobblestoned, flowing downhill from the cathedral. The cathedral is a massive stone structure, with a large, stark wall culminating with the entrance and belltower. The structure has an almost medieval feeling to it, a more formal work of architectural design than found in other small towns in the area. The plaza is lined with structures consistent with a colonial aesthetic, whitewashed plaster with terracotta tile roofs, two-level structures with narrow, linear wood balconies and wooden doors.

Occasional statues of people in local garb are visible around the plaza. Flowers abound, from the banal geranium to somewhat more exotic flowers, completing the colour scheme so typical of the Colombian highland towns.

Bushes are trimmed in odd shapes, creating the feeling of an errant English garden on the cobblestone plaza of the Colombian highland town. The level of detailing in the architecture is impeccable. The skies offer another part of the picture, dramatic cumulus clouds layered far into the heavens, complementing the aesthetic beauty of the town.

A few groups of young students are present, some old people hobbling over the cobblestones, and some other locals, surveying the revenue possibilities of the latest batch of arrivals. It all seems very romantic, except the town is showing signs of selling its soul to tourism, not a common quality in these highland towns (other than perhaps Villa de Leyva). On the side of the plaza, I see some visibly indigenous faces and also hear a non-European language being spoken. So it could be that people in this region do maintain their original languages, at least to some extent …

The obligatory walk through the blocks that surround the plaza ensues. The road I take to the backside of the plaza drops off considerably and reveals even more striking views of the hillside surging above. The aesthetics of the town are consistent, with whitewashed walls and terracotta roofs, although in the core of town, the green theme is not as evident.

It must be quite the chore for the locals to have to trek up and down the steep roads in town here, never mind working in their fields in this hilly landscape.

There are a number of inexpensive-looking accommodation options around town, which may be an issue, given that I am considering coming back to Mongui to hike the Páramo de Ocetá once I am finished in the Parque Nacional Natural el Cocuy. All of the outdoor activities are weather-dependent of course, given that higher up in the mountains, the weather will be worse than at this elevation.

Once the possibilities of walking around Mongui have been exhausted, it it is time to board the waiting bus for the encruce below, which branches off to Tópaga and Mongua. A short wait with a skittish young local at the encruce, and then we gradually rise again amongst the grassy fields and pasture lands towards Tópaga.

My companion on the bus tells me the first town is more interesting than Mongua, but since I am already on the bus, I continue to Mongua and hope for the best. Tópaga is hardly very appealing, other than the bizarre sculpted trees that populate the plaza.

Am I ever glad I stayed on the bus. Upon leaving Tópaga, the landscape becomes stunning, the road weaving along the side of verdant mountains, often along cliffs, with continuous views of the valleys far below and the faces of the steep hills across the valley. Further into the mountains, the weather turns from sunny and warm to heavily overcast, with dark rain clouds threatening overhead.

Mongua is small but more dramatic than its neighbor, the narrow road weaving to the central plaza, which is winding down from a weekend feria, the snack and sweet stands as well as the stands selling sombreros desperate holdovers from the weekend. There had been live music, what with the stage being taken down.

The plaza is still lined with Tecate-branded canopies. It seems surprising to see such a triste hill town devoted to such a degree of festivity, although now the place feels anything but festive, what with the skies closing in, the first drops of rain falling, and the few local folks more dour than ever.

The central plaza takes the same form as its brethren towns, although falling somewhere in the middle, and certainly not as pretty as Mongui. The cathedral seems new, possibly a replacement of an earlier version damaged in an earthquake. Renewal is a constant here, what with the reputation the region has for earthquakes. And unlike the other towns with their flowering gardens and trees, Mongua has no more than a few rose bushes here and there, providing some fodder for meager photo opportunities.

There is little traffic on the road. The occasional young locals in school uniforms greet me with a diminutive ‘buenas tardes’ as I amble along the alleys of the town, the wild landscape surging to either side. Based on my experiences with people in the villages in the area, I try not to greet or make eye contact with locals, ie. Be pleasant enough in conversation, but otherwise aloof.

I would love to take photos of locals, especially wearing the ruanas and sombreros, but their ambivalent nature makes me circumspect and uncomfortable doing so.

One strange sight I have seen here is tuktuks. I can not imagine seeing the classic three-wheelers outside of South Asia, but here they are. They obviously must be able to climb the steep hills, which is amazing. They are certainly more appropriate for the high gasoline prices.

One last circuit around the plaza of Mongua, where I see the indigenous people I noticed before. It turns out they are from Ecuador, spending a year in Colombia visiting markets. I inspect the ponchos they are selling, admiring the soft texture, but the woman disconsolately concedes that they are synthetic, and made in China.

Apparently, alpaca wool is very expensive now even in Peru, and Ecuador has very little of it anyway. I am hardly that judgemental: so much of the world wears synthetics, it’s all the same, and the local raw sheep wool material is unbearably raw and uncomfortable.

I find the Ecuadorians quite warm. In Colombia, I miss the vibrant colours of the indigenous cultures found in Peru and Guatemala. Colombia is probably rich in native culture, although the indigenous and Latin cultures seem largely integrated.

The population of the highlands of country is certainly quite aloof as well. There are many superlatives that could be made about the region, but not regarding the warmth of the people, at least in this region.

I am actually happy to be back in Sogamoso. The small towns I have visited may be picturesque, but there is little going on, and the communities are very tightly knit, closed to outsiders. It is nice to wander around the towns, but there would be little else do. In the city, a world of options open up, however modest they may be.

One more piece of the Sogamoso puzzle falls into place. I discover that the road through the new developments on the periphery of town is basically the extension of Carrera 11, information of little use to anyone other than myself at the moment …

I make sure to get off at the park at the top of the pedestrian area of Carrera 12. I am famished … highly ironically, walking down Carrera 11, I would probably love to eat in any of the establishments I dismissed earlier on, coming from the nonentities of the local small towns.

But I know I can’t afford to, and have to get to the gym. I would in fact love to do as little as possible for the remainder of the day, but that is part of the problem of not working out. I also feel worn down from the constant and terrible air pollution here.

At the locked hotel door, I buzz and buzz – no one answers. Seriously – the staff barricades the hotel, then abandons it so guests cannot enter?

I actually make it to the gym, which kind of shocks me, as I had been getting lazy. I lumber through my routines, using less weights than I normally would, in part because I am concerned that the equipment may break and leave me with some serious injuries. But once I have finished my routine, I have another problem: at 9:30 pm, the city is shutting down, and there will be very few places to eat left. And all I have left in my pocket is 11,000 pesos, which doesn’t buy much in formal restaurants.

The most likely locale for open restaurants would be the north end of Calle 11, in the area of the university, quite a walk at this time of day with the streets quite empty. Several men’s blurred voices yell at me for money as I stride briskly north on Calle 11, the smell of glue wafting past me.

I normally would avoid a pollo asado place like the plague, but in this case, it is a good choice, as it is one of the only places left open, and pollo asado is still available at 11,000 pesos. I debate as to what I should order, then decide on the ½ roast chicken. That doesn’t seem to have registered with the waiter, who is busy playing with his boisterous children. I remind him of my order, but then change my mind and simply leave, the children’s high pitched squealing a bit too much for 10 in the evening.

The cavernous Dorado de la 11 on the Plaza 6 de Septiembre provides an admirable option, although I had originally thought it was a Chinese restaurant. The pollo asado is very basic, although ½ a chicken is a lot to get down, especially factoring in the baked potatoes. And yet the food is actually quite good, never mind the aji, which I use most of on the delectable chicken.