April 13th, 2015

The banging and shouting this morning can at least be accounted for by a large group of visitors that arrived from Yangon at 5 am, two of whom are actually young Englishwomen, telling me the story of how they came to be in Myanmar. One is from Cambridge and the other from Rugby, venerable English enclaves, one having come here for a month to work every year for the last decade, and the other having actually lived here for the entire last decade in the capacity of nursing and medical care.

The country has changed immensely, and while a lot of it may be for the better, the perennial concern is that the underlying spirit and culture will be eviscerated in the same way that has been experienced in Thailand. The one who has lived here for the continuous ten year span enjoys the commercial indulgences of the neighboring country, but is always happy to return to Myanmar.

She stumbles through rudimentary Burmese to order her breakfast, a slight lot more than I am capable of doing. Breakfast conversation is short-lived, however, as I am slated to finally head out onto the lake on a vaunted boat trip, not that I am particularly motivated, especially given the probability of rain today.

Paraphrased from Wikipedia: Inle Lake is one of the largest lakes in Myanmar, measuring almost 120 square kilometres, and is located in Shan state. Inle Lake features unique species of fish, and has been designated a UNESCO site. The so-called Intha people live in a series of townships flanking the lake, and consist of a diversity of ethnicities.

A characteristic form of rowing is used by fishermen on the lake, involving wrapping one leg around the oar in order to be able to stand and maintain better visibility over the dense vegetation growing on the lake. Plant matter is collected from the lake and assembled into floating gardens on the lake, held into place by means of bamboo poles. These floating gardens are provided substantial nutrients from the lake water and are also immune to the effects of flooding, as they are already on the water.

The natural beauty and cultural heritage of the lake are under threat from both economic development, pollution, the use of floating gardens, and the large scale of tourism visiting the area, as I will be witnessing during the day.

The continuous row of longboats lining the canal is being steadily filled with passengers, the vast majority local tourists in no way restricted to the small numbers designated for foreign tourists.

Our boat edges carefully into the canal, the boatman’s positioning of the vessel confusing until I realize that the lake is actually in the opposite direction. We follow the sequence of boats into the wider canal, judiciously staying far enough behind to not get drenched by the spray emanating from the boat engines. Further towards the lake, boats are capable of fanning out and creating some distance from each other.

The prized photographic catch awaits us immediately upon broaching the lake, local fishermen posing on the lips of their narrow wooden boats, one leg balanced on the boat with the other wrapped around the paddle, long nets in hand, with no apparent intent of actually fishing.

Further onto the lake, more genuine efforts seem to be in progress at harvesting the sea grasses growing in abundance on the lake, men bracing their legs against the rims of their boats as they wedge their pitchforks into the water, extracting the oozing green material from the water and loading it onto the boats, waiting to be transported towards the shore and used as fertilizer.

We traverse fecund patches of the lake congested with extensive gardens of the sea grass, the line between the waterborne environment and terra firma gradually blurring as we delve further into the Inle biosphere.

The smattering of thatch huts along the lakeshore is interrupted by sprawling resorts, more visible as we passage deeper into the lake’s overgrown channels later on, although it is not quite clear how the dense grid of teak houses on stilts set deep in a marsh environment could have the makings of a luxury enclave.

Small thatch huts line the channels, unlikely homes for the denizens of the lake, possibly intended as sheds or storage spaces. Judging by the proliferation of clusters of raised houses alongside and throughout the lake area, the population here is far from insignificant, almost difficult to imagine as sustainable. And judging by the overwhelming number of boats full of locals with no demonstrable connection to local agricultural practices racing across the shallow water, it would seem that tourism provides the prime mode of survival.

It becomes apparent that the boat trip is relatively inexpensive for a very good reason – every stop while sputtering through the narrow canals is to a shop flogging local artisanal products and general touristic claptrap. One establishment leads to the next, the apparent hospitality gratingly insincere and bent on nothing more than selling overpriced dross to the tourists, unsuspecting or otherwise, with the intention of leaving boat owners with their own healthy commissions.

In fact, upon closer inspection it becomes amply apparent that there is little purpose to the communities of shacks raised on stilts above the shallow canals lining the lake other than selling souvenirs to tourists or feeding visitors. Columns of boats wait in line to navigate the shallow channels leading to the next shopping experience, the shelves of neatly arranged silverware, wood carvings, masks, statues, tribal claptrap and puppets leaving me increasingly indifferent, motioning each time to the boatman to just continue on.

I expected little of the trip to the lake, but what I am experiencing is an utter farce. Perhaps at some point in the past spending time at Inle Lake could have been enjoyable, but this visit reflects very little sense of cultural authenticity. It seems as the only raison d’etre of the Inthar people is to sell souvenirs to tourists.

But just as pointless as the exercise of visiting the lake would seem to be, as warm and welcoming the local passengers occupying the endless procession of boats are, from the young men in baseball caps hunched somewhat indifferently in their seats to the hordes of women clustered together along the bottoms of the boats, all wearing identical floppy straw hats.

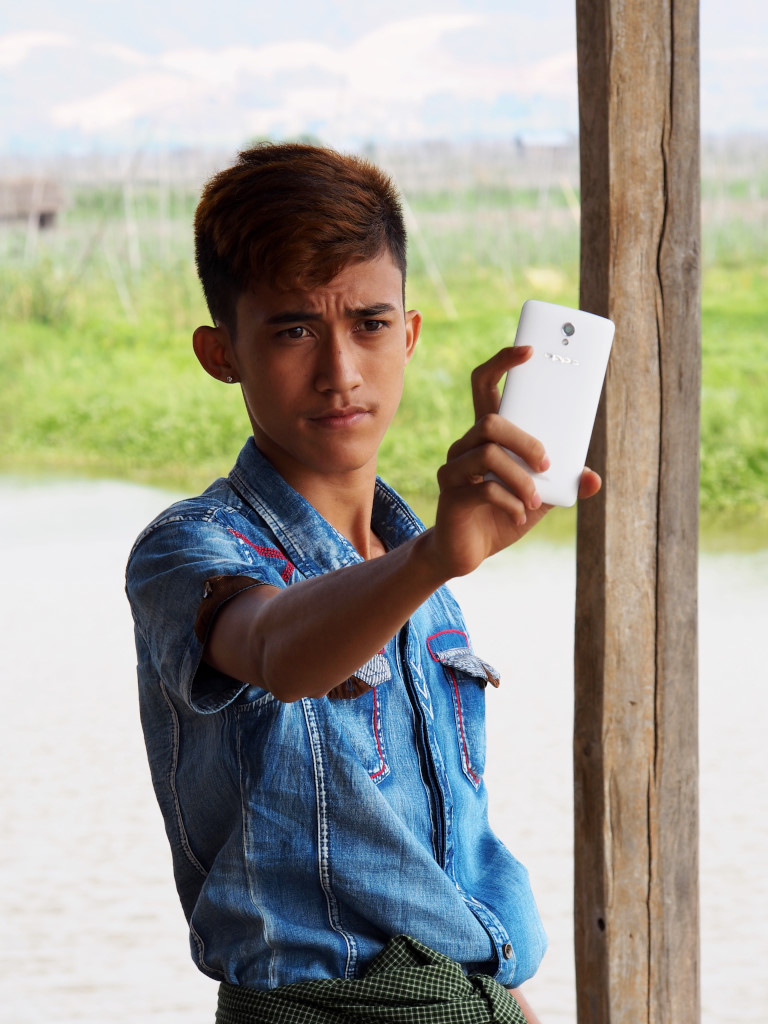

From one boat to the next, the passengers smile and wave, and in the shops, their curiosity endlessly aroused. For the number of foreigner visitors here it would seem inconceivable that the Burmese are still so fascinated by foreigners.

The trips along the canals emanating from the side of the lake are far from straightforward, given the sheer volume of longboats plying the turgid waters. We wait in single file, some boats curiously bunching together, one boat overtaking the next, then sliding back, the motors mounted on the long poles artfully dipped into the muddy water so as to create the necessary thrust without undue amounts of spray hitting the following boats.

Small bamboo dykes are erected at intervals with marginal gaps in the centre intended to limit traversal to the middle of channel. Presumably a lot of the complex choreography of the boats is due to the shallow water, although getting us to the next shopping opportunity is an absolutely must!

Prior to disembarking, locals with floating storefronts already sidle up to us, imploring me to buy any of the merchandise laid out on the bottom of the bottom before moving on to the next in the endless procession of boats trawling through the passages. The tooled silver chalices and plates, jewellery, carved mother of pearl, selection of knives, and other fine objects command elevated prices that may or may not be worthwhile.

The Kayin women pretending to weave in the corner of the deck while looking intently over the stack of golden neck rings are almost perturbed at my departure, perhaps even more at my reappearance, given that I forgot my day pack at the store and for which we had to trawl all the way back through the watery traffic jam.

Well, if the boatman resents the time we lost returning to the store, I would just as happily skip some of the other stores on the list. As pointless as visiting the establishments posing as authentic lakeside village residences is, even more pointless seems the efforts of the bedraggled locals shoveling mud out of the channels and into waiting longboats, a very arduous way of deepening the passages indeed.

The store selling fabrics may be overpriced but offers more of a social exercise of meeting other travelers, especially locals, never mind the adjoining terrace serving coffee and drinks.

Later in the afternoon, it comes almost as a shock that we visit some attractions with a genuine cultural component. One of the claims to fame of the area is the set of markets that rotate between the principal villages on the lake as the week progresses. Masses of vendors in traditional costumes are loading up their boats near the jetty of one town, its presence defined by the hulking multi-sided squat pagoda that silently witnesses the frenzy of activity below.

The stands on the plaza outside the temple are devoted to the predictable sale of tourist claptrap. The bulk of locals haul their heavy wares circumnavigating the broad temple towards the water on their return trip home.

It seems almost inconceivable that so many people manage to find their vessel amongst the morass of longboats clogging the harbour waters, although to make matters more confusing, many of the boats probably belong to Burmese tourists on one of their obligatory stops around the lake. To the side of the harbour, the golden griffin-fronted vessels await more decorous excursions than awaiting the pedestrian melee below.

The last stop is to the antique teak temple, its dark interior a welcome respite from the day’s retail extravaganza, the row of large golden devotional figures intricately carved and solemn. And finally, we return across the lake, the still waters and clean air refreshing, although the sight and smell of rain is not far, the skies fortuitously erupting only as we approach Nyaungshwe’s bridge.

The long day’s excursion begs a rich black coffee at the green and yellow bamboo-stripped establishment on the main road, a few other travelers also settling in for the late afternoon rains, including Michaela, a young Dutch woman from the area of Eindhoven and Sandy, of Pan-Canadian roots, but for years having been teaching in a variety of countries, including Zambia, Chile, Myanmar.

Not surprisingly, the conversation between Sandy and myself takes off, given that we are irrepressible chatterboxes. Sandy was born and raised in Northern Ontario, lived in Toronto, has family in the Maritimes, and counts as her antecedents some of the earliest Acadian settlers, with her children currently living in south Vancouver Island, and her own most recent place of residence in Canada Canmore, Alberta.

But now she is a person of the world, loving her life and yet unsure where life will take her to next. She absolutely loved Chile, but has little time for other countries, such as India or for that matter African countries, where the fact of not being able to venture into the street as a woman alone without a high risk of getting gang-raped by men almost guaranteed to have AIDS is utterly unacceptable.

Closer to home, she concurs that Thailand is no cakewalk, given the extent of the country’s economy being based on sex tourism, lamenting that Myanmar would even remotely risk going the same direction. But then Thailand’s problem is a phenomenon that was started up by the American soldiers during the wartime and only got worse over the years.

And then the Philippines is even worse … She comments that gonorrhea has skyrocketed in China what with the number of young Chinese women who want to throw themselves on any Caucasian man. Our conversation continues with its lurid twists and turns but I really have to go, the day’s journal entries awaiting my devoted attention.

Back at the hotel, I write for a while, then the power goes out, and for a considerable length of time at that. Wait – the hotel’s rack rate is above $40 US in one of the poorest countries in Asia, and they have no working generator? Utterly appalling – and reason to lie down and get some rest, only that it causes me to arrive late at the Sunflower restaurant where I had agreed to meet Sandy again.

She sympathizes about my complaints about the meager quality of service in the hospitality industry viz the prices being charged in this country – her own roommate in Yangon always rails on about the same thing, although Sandy’s particular beef is the inability of the taxi drivers to find anything in town despite having smart phones.

I shouldn’t spend too much time complaining about Myanmar costs because if I was in South America it would automatically cost a lot, lot more. I point out that the infrastructure in South America would also far more manageable, sophisticated and transparent. She comically refers to the country as Miramar, possibly subconsciously wishing she was in a resort in Mexico.

As the evening progresses, I continue to fret about the possibility of continuing onwards despite the lack of formal transportation of any sort in the country during the period of Thingyan, not wanting to be held hostage by the festival that in the end is of little meaning to me.