January 31st, 2018

One last breakfast at the restaurant tipico next door. The same food, caldo de costilla, scrambled eggs with aji, soft buns and hot chocolate. Neither my friends or the resident dog are in attendance.

In packing, I realize my red North Face rain jacket is missing. The restaurant downstairs doesn’t have it, it’s not in my friends’ room, and so the only choice that remains is the Restaurante Kiosko de los Caciques, where I ate yesterday evening. A cramped cab drive to the bus terminal, and when I approach the back of the restaurant, I already see my jacket hanging from a chair. I thank them profusely, but also for the excellent food.

Another depressing bus trip may be in the offing for me, given that many of the seats on the van to Tunja are either broken or with virtually no leg room. My friends are intent on taking this van, but I would rather wait until a real bus leaves that wouldn’t encounter such problems. Well, I can probably take one of the front seats and make do.

Rejoining the main road, there is no significant elevation gain or drop, nor does the road weave substantially, maintaining its trajectory along a valley floor, the steep hillsides that were so verdant further to the west now increasingly arid, as if the rain clouds stop on the western flank of the highlands of the Paramo de Iguaque and above, leaving the eastern side arid.

Tunja is set in an arid valley, the dry hills rising on either side, although the town itself is also quite hilly and features escarpments that lend it more character. We weave through the narrow streets, the town stark on the surface, but suggestive of subtle touches of whimsy in the same manner as the capital, but on a much smaller scale.

The bus station is cramped onto a small lot to the south of the city, where I clamber around to find anything resembling a taxi stand, while my friends hunt down the bus to Sagamoso.

The taxi brings me to the Hotel las Nieves II, closer to the bus station than I would have expected. The presentation of the room in the second floor hotel and the fact of being located in a historic structure some 2 1/2 centuries old provide very good reasons for being here, but the somewhat intense matronly owner who clearly hovers over the entrance, and whose watchful gaze is nigh impossible to avoid is always nearby, lends the experience of staying at the hotel a sense of unease.

The dominant theme is wood, polished wood floors and wall panelling, in addition to a heavy wooden bed and cabinets, lend the room copious amounts of character, despite the considerable amount of noise entering through the windows from the street. The room also feels somehow worn out and tired, an effect underlined by the intense noise and exhaust fumes generated by the endless traffic reverberating below.

Tunja is another incredible surprise, nothing I had expected, and the fact that most travelers skirt the city a sad commentary on the divergence between truly interesting locales and what travel media advocates. The city is a paragon of Spanish history in Colombia, one of the oldest cities in the country, one of the most important university centres, and with a bustling historic centre second to none in the country. Tunja is now the capital of Boyacá province, and prior to the arrival of the Spanish, it was a Muisca city named Hunza.

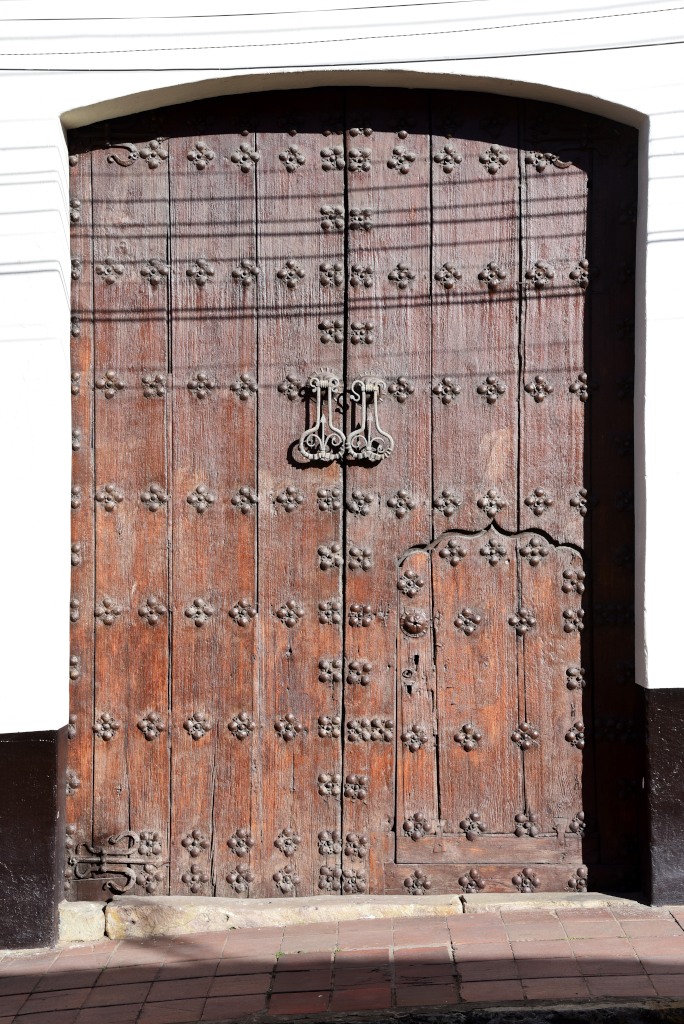

The town centre rises above the street the hotel is located in. Climbing the street, an impression is made of small spaces, elevation, dry desert air, historic colonial architecture that closes in as one approaches the expansive Plaza Bolivar with its centuries-old low-slung colonial palaces. The square is very large, but competes with even far more immense squares in the likes of Villa de Leyva.

I wander around the plaza, looking at the architecture, but of course also at the crowds of people flowing from all sides, a stark contrast to the sparse numbers inhabiting the centre of the town I just came from. The crowd is diverse, large number of students, academia, business people, but also working people, never mind the visibly disenfranchised.

I carry my camera openly, pointing at diverse subject matter, but it probably would be good to remain somewhat aloof with so much human traffic flowing around me. The plaza itself has only a few cafes, hardly representative of the enormous number of coffee drinking establishments and bakeries I will discover in the course of the afternoon.

At a place facing the cathedral, the young and fashionable serve all manner of coffees and alcoholic drinks to a few tables, a narrow staircase leading to an upper floor. The space is confined, but full of character, what with the wrought iron furniture, heavy wooden chairs and illustrations on the wall.

Remembering that the reason for spending time in Tunja was to attend museums, I visit the tourist information office on the Plaza Bolivar for more information on the exhibits I should be seeing. The most important one is apparently the Museo Casa Del Escribano Real Juan de Vargas, which happens to be in the same building as the tourist office, and in fact, if I hurry upstairs, I can catch the tail end of a tour of the museum.

The museum is located in the former house of don Juan de Vargas, one of the founding members of Tunja in the 16th century. The house passed through various hands over the centuries, and earlier in the 20th century was appropriated by the government and converted to a museum. As much as possible was preserved in the original state, although the centuries that have passed have inevitably made it more difficult to determine the exact state of the original residence. For one, the frescoes on the walls have mostly been lost, and it has only been possible to restore select portions.

The frescoes on the high ceilings are fully intact, taking the form of archaic stylized subjects with presumably symbolic meaning. Every room in the upper floor that comprises the museum had its purpose, including a kitchen, bedroom, and oratory.

The presentation of seals of the family in the hall, set against a backdrop of the heraldry of the king of Spain, established the degree of privilege of the family.

Our guide may be passionate about presenting information on the museum, but then also sad at the general state of support for cultural efforts in the country. After a short discussion with myself, the young women from Trier and man from Bogota, I am off into the garden below for a few photos, then to the Casa del Escribano Don Juan de Vargas just around the corner, a museum dedicated to one of the early figures of Tunja’s history, a man who came to exploit the wealth of gold of the native people for the purpose of buying a noble title from the king of Spain.

My understanding is that his son was driven from town due to his father’s excessive exploitation of the native people, although I may have misunderstood. The house was abandoned after the family was banned from the town, and was only rediscovered last century when work began on restoration.

Valiant efforts were made to restore the house. The house is also characterized by the spaces that would have been typical for houses from the founding era. Some rooms are replete with period furniture and paintings, although their 18th and 19th century nature would be inappropriate to the era of the family that built the house.

The stern matronly guide recites the relevant details pertaining to the house in a flat, monotone voice. She is insistent that no photos be take of the house, with or without flash, a rule that makes me upset, but then she didn’t come up with it on her own.

Tunja – at least the centre of town – has a substantial amount of character, given the colonial nature of the architecture, and the manner in which the colourful historic buildings drop off towards the valley below, visible from every narrow street receding to the east. The dry, sunny weather gives the town a unique character, a climate that would have found a lot of favour with the Spanish settlers.

The establishments that line the street typically have modest aspirations and are confined to small spaces, but nonetheless, particularly the many cafes reflect a unique character. The small spaces and narrow streets also lend the town a strong sense of intimacy, particularly with the number of people crowding on the narrow sidewalks.

The original Muisca name of the town was Hunza, an evocative name, given that is also the name of the dramatic region in the north of Pakistan that provided inspiration for the idea of Shangri-La. The name appears on buildings, institutions, hotels, although only the vaguest traces of the original settlement remain.

Due to the plethora of poorly maintained engines that burn copious amounts of oil, and the fact that vehicles have to struggle up steep hills to reach the inner core of Tunja, the narrow streets are filled with billowing clouds of black smoke, not something that is enjoyable at the best of times.

And yet cyclists are still in evidence, bravely pedalling up the steep hills, young students, professionals, older working class people, and men in full lycra uniforms on racing bikes. And next to no one wears a helmet …

Behind the Plaza Bolivar, I discover a clutch of hotels that offer a much better option to the slightly noir establishment I am staying in, and for only slightly more. Of course, without booking through online resources, prices are considerably lower. Three or four smart spacious hotels with a sense of comfort are set out in the narrow streets that drop off steeply to the sun-washed colonias in the valley below.

The Hotel Casa Real is the one I would unquestionably return to, with its ample beds, whitewashed walls, high ceilings, well-appointed bathrooms, with tasteful contemporary oil paintings and artwork set in a historic structure. The courtyard is ample, replete with plants and comfortable furniture.

I am amazed by the small shopping malls in Tunja. It would seem odd to comment on such as subject, but these often narrow passages featuring a variety of miniscule shops arranged over several levels are quite charming, with the common area on the main floor devoted to one or two cafes, with an often liberal selection of plants. These commercial spaces strike me as both an efficient use of space as well as high on charm.

Weaving through the narrow streets back towards the vicinity of the hotel, incredible crowds surge onto the streets, inexorably concentrating closer to the plaza. The late afternoon golden light washes over the historic edifices of the city, with luminous cumulus clouds etched over the hills on the periphery of Tunja. The lively early evening here is in stark contrast to the abandoned feeling Villa de Leyva had on weekday evenings.

I am not really hungry, but recognize that as the afternoon recedes, I will have to eat somewhere. And other than a few expensive restaurants, pretty much everything on the street is deep fried or starchy. There may be a few tipico restaurants amidst the fast food joints, cafes and panaderias, but they would be very innocuous, miniscule or uninspiring.

The hotel owner recommends that I try some of the places next to the San Rafael hospital, and she is right. The Tendencias eatery features an extensive and inexpensive a la carte menu, but also an all-inclusive menu with the usual, this variation including a stewed squash preparation, beef cutlets in sweet-sour sauce, a potato soup, and a ginger beverage, all for 8,000 pesos, very much the kind of thing I was looking for. I find it interesting that one would have to leave the core area to get decent food …

In the distance, a noise emerges, gets louder, then louder yet, pounding cans, drums, blaring horns, and then finally, from the windows of my hotel room, I see the parade of people passing by, with some police presence, finally disappearing again, then eventually returning. It turns out that this is a parade protesting tax hikes, something that has taken place in the major Colombian cities. The issue pertains to property taxes, that have almost tripled over the last year.

I find it ironic that the major Colombian political parties are spending copious amounts of money on renting spaces everywhere for candidates in the upcoming Congressional and Senate elections, with often expensive vehicles emblazoned with party logos ubiquitous, even in remote village environments. The amount of money being spent on these elections is completely out of line with the relative poverty of the country.

Finally, around 10 pm, the noise dies down considerably, the city becomes quiet other than the occasional vehicle roaring by. With such a loud location, it would probably be very advisable to go to bed as early as possible, as the noise levels will amplify in the morning with a vengeance. But the loud traffic continues, never mind the heated voices of locals on the street into the early hours of the morning.