April 22nd, 2015

The peace of the Mrauk U night is interrupted by a distant rumbling that gradually approaches, the brilliant flashes of light followed almost immediately by deafening explosions of thunder, the sound of the pattering rain gradually dissipating as I drift back to sleep.

A long drawn-out discussion at the long wooden breakfast table ranges through the morning, the young Dutch couple avoiding me at all costs. Any travelers worth their salt have long since been up and off to the temples, beginning with the 5 am climb up the hill behind us to take in the sunrise, which I had no intention of getting up for.

Given the relative English fluency of the owner’s wife, she is forced to listen to my rants while nursing her infant son, subjects ranging from the poor infrastructure of the region, the reliability of transport, the gratuitous exploitation of tourism in this incipient market, and the pros and cons of the treatment of Rohingya, a very delicate subject here.

Power apparently used to be very expensive and unreliable, but now that large amounts of gas have been found off the coast near Kyaukgpyu, the price of electricity has dropped to a fraction of what it used to be, although most of it is going to China, the financial benefits largely accruing to Rangoon.

China promises to build a good road from Rakhine state to China, but there is no money to connect the state with a better road to the rest of the country, which is much more important to the residents of the area.

And now fighting has broken out again with the Rakhine independence fighters, but the road going through the upper Keladan should be secure – one more thorn in the side of traveling here. She tells me she knows little of other parts of Myanmar, what with the isolation of Rakhine state from the Irrawaddy basis and overall lack of formal roads.

I weave into the conversation my elaborate assessments of the widest ranging subject matter, although eventually it is time to amble out into the desultory late morning and explore some more of the sights. I should visit the bicycle rental shop and pay for another day’s use, but I can probably worry about that when I return the bike prior to leaving town.

Returning to the centre of town, the remains of the Royal Palace beckon, although the wide terrain centred in town amounts to no more than the remains of larger segments of concentric walls with occasional archways and staircases breaking the linear monotony, the broad green canopies framed along the periphery of the walls. The raised ground within the walls themselves are covered with a linear grid of square trenches, possibly for the purpose of archaeological excavation.

The weather is hardly very inviting, and of the relatively few tourists visible in this town on any day, the fewest would bother coming to the palace walls. Certainly no foreigner is visible here at the moment.

The entrance to the museum space looks somewhat regal, featuring the predictable assortment of Buddha statues and affiliated artifacts in the cavernous space. The steep 5,000 kyat admission fee motivates me to move on, however.

The next item on the agenda is acquiring a boat ticket to Sittwe, having now decided that Sittwe would be my final destination in the country. I hope and pray that the return trip to Yangon takes place in a relatively smooth and predictable fashion, which is probably a long shot, but it’s the best I can do.

The road through the ramshackle disarray of the market area continues on through the lush area of the canal, and then down along the shoddily-built housing compounds – low on precision and large in atmosphere – to the jetty, where the entrance to the river could only euphemistically could be referred to as a port.

Brightly painted longboats compete for space with smaller vessels laced with heavy wooden cross-beams along the untended mud banks. The odd bicycle rickshaw driver eyes me skeptically as I roll over the bumpy trail towards one of the shacks.

I am pointed further along the shore, where a young man seated in a thatch enclosure peruses his ledger covered in minute scrawls, elaborating on the departure schedule the company he works for offers towards Sittwe. Unfortunately there are no departures on the 24th, which is the day I wish to travel.

Large bundles of bamboo stripped and roped together are layered in the form of large rafts on the open water. Men wading through the side channel surreptitiously keep their teak lumber submerged in the water and out of sight, possibly a condition imposed by the bribed local authorities, given that the exploitation of this timber is largely prohibited.

A flash, and an oversized canoe races by along the far bank, a phalanx of young men rapidly dipping their paddles into the water in unison.

A wizened older man assures me that the river water may be salty now, but in the wet season is largely sweet, promising a diversity of seafood over the span of the year.

Local women load water jugs and other vessels into their longboats, then weave past the bulky low-slung ferry boats that are quantum leaps more modern than any of the boats in the vicinity. Dark Rakhine men young and old with cheroots artfully hanging from their mouths disembark from incoming boats.

I always find it fascinating that the Burmese men never seem to risk losing their lungyi, irrespective of the contorted movements involved in their work, such as steering, anchoring or tying down their boats.

Life is even slower at the ticket office of the competing ferry agency, where the older agent is slumped in his chair on the creaking narrow verandah of the dilapidated wooden shack. He is intrigued by the stories I tell about my country. While his $10 ticket to Sittwe is half the price of the competition, I also have to be here at 7 in the morning …

There is little point of even returning to the Shwe Moe eatery where the thanaka-caked corpulent matron seems to be engrossed in erratically yelling at members of her extensive staff, conveniently ignoring my presence. But I gave her 25,000 kyat yesterday – and I want to see my bus ticket. Finally, she comes around to my table, her typically hoarse voice somewhat toned down, telling me that I should come back in the evening.

She doesn’t want to deal with the ticket issuance now that her restaurant is flooded with customers, thus leaving me to worry about the legitimacy of the transaction. One thing I cannot afford is getting stuck here, especially considering how far away from the rest of the country Mrauk U is, and that I have a flight out of the country in a few short days.

The day’s housekeeping taken care of – at least the activities that don’t involve an internet connection – I am free to return to the area of the canal dividing the Vesali and Prince hotels from the centre of town. I veer eastward to the ancient temples, strung out along the rudimentary dirt road weaving amidst the rambling thatch and raw teak houses, and set out on the rust-coloured earth, caressed by the heavy olive foliage.

Children play erratically along the barren escarpments, their imaginative world a far cry from the conceptualizations of the adult world. Over-amplified traditional music blares from speakers at a neighboring compound, announcing the beginning of festivities celebrating a local temple, of which the speeding canoes I witnessed earlier on are taking part in the form of competing races.

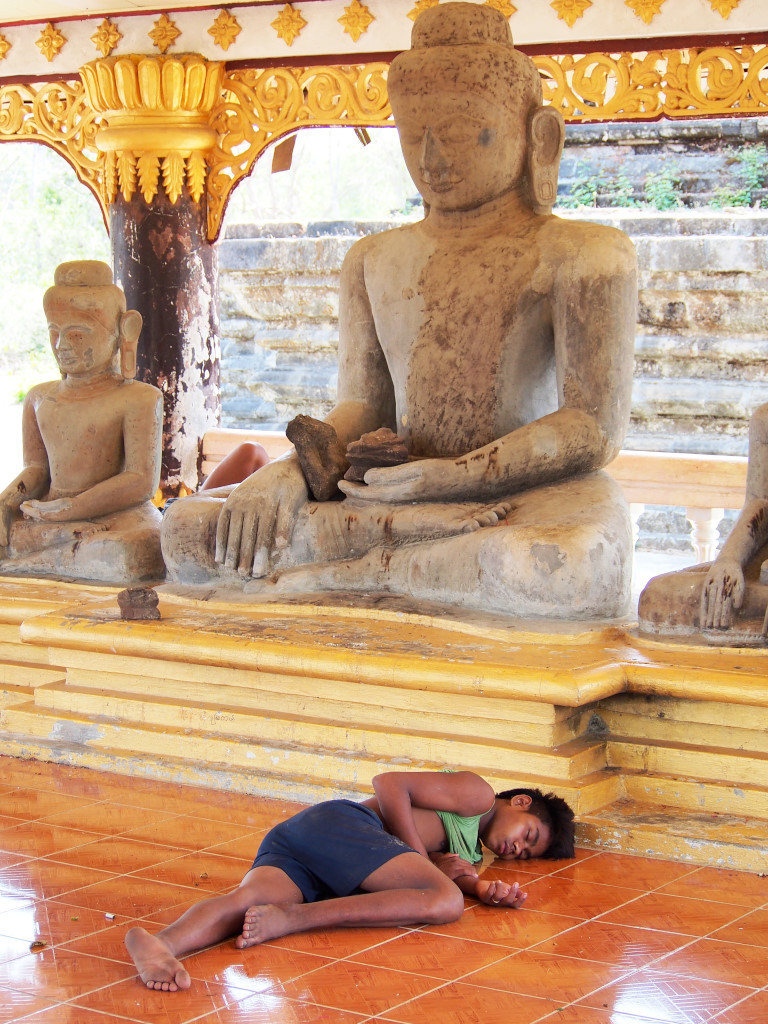

A smaller enclave en route to the major temples is situated further along the road. The Mong Khong Shwedu is nothing more than the usual darkly-weathered inverted bell on a patch of cleared land, the neighboring pavilion brightly adorned with golden bargeboards a contrast in colour. Any notion of the sacred is lost on the young men sleeping around the trio of stone seated Buddhas and feral group of tatty youngsters engrossed in a game of soccer.

The rounded peak of the conical structure begins with a geometrically-stepped base, the angled sides fronted in each cardinal direction with delicately embellished facades. Naga-shaped arches of dual false porticos house sedately seated stone Buddhas. The rounded lips of each of the succession of shallow ascending terraces feature no further adornment.

A scattering of rambling thatch structures welcomes the visitor to a stone staircase leading up to another stupa of similar provenance, the perimeter of the base lined with a continuum of alcoves, which house seated Buddhas in an identical mudra pattern, the single decapitated image coming as a slight shock.

The crown of white frangipani blooms, a standard adornment at Thai and Lao temples, but much rarer in Myanmar, also comes as a modest but welcome surprise. Ilaria and Ian, the young outspoken backpackers encountered in the Moe Cherry yesterday appear, seemingly intent on spending the afternoon taking in the eastern group of temples, although the hours spent chatting about a diversity narcissistic travel subjects does little to enhance either of our experiences of the local culture.

They claim to have been traveling around the world for 2 ½ years, although in reality they were really traveling and working in Australia and New Zealand for most of this period of time before coming to Southeast Asia.

As with most younger backpackers, they are much more motivated, engaged, and less neurotic than I am, her natural Italian enthusiasm tempered by the litany of clichés of her culture I feel compelled to parade in our conversation. On the other hand, when it comes to the subject of food she melts, begging me to stop, confessing that she is counting the days before being able to land back home and gorge on good Italian food. ‘Coffee?’ she scoffs – not here or for that matter anywhere else in Southeast Asia. As renowned as Vietnam is for its coffee, they found it appalling, and the real thing phenomenally expensive.

She continues on about the freewheeling and enlightened world backpackers such as themselves are privy to, free to be wherever they want to and experience the world of others at whim, not bound to be locked into the confining mental imprisonment of people who go to the same jobs all their lives, whose only freedom is to attend football matches and behave like hooligans on the designated day of the week.

He is far more laconic, although the humour and insight is never far away from his Glaswegian temperament. They reiterate that they want to establish a life together in Europe in neutral territory, in Portugal, for example, where there is little money to be had from work, but land is still cheap, and they could establish some sort of cooperative farm, eking out a subsistence in a hopefully welcoming Mediterranean culture that is comprehensible to her temperament and far warmer than anything he would want to contend with back home.

It is time to move as the afternoon light is again waning. I feel the days have progressively been flushed away by lengthy and invariably inane rants with every set of backpackers that passes by. Then again, this is genuinely an aspect that I love about traveling in relatively offbeat places, the possibility of meeting relatively like-minded free spirits in highly incongruous and arguably incredibly memorable settings.

Except while they can organically wind the day’s experiences down with a tranquil beer or two, I am strapped with my self-imposed burden, recording the day’s minutiae in my typically overpriced hotel rooms, attempting vainly to maintain concentration while I labour over my journal and photos.

However, my concentration is now completely focused on the massive structure lying ahead on the dusty road flanked by small tended plots, the squat and imperious Koe Thaung paya, another stellar example of how the architecture at Mrauk U is dramatically different from any other Buddhist temple structure I have seen in neighboring countries and India.

The central stupa is purely ornamental and almost disappears atop the vast bunker-like structure. The sides bristle with continuous rows of identical and smaller bell-shaped stupas stepped in shallow formation towards the upper terrace, ascending in turn toward a broad courtyard. The walls of the courtyard are flanked with staggered rows of slightly variant small Buddha figures, whose original linear alignment has been thrown awry with the degradation of the underlying structure.

Koe Thaung is considered a living temple, and hence removal of shoes is required here as at all other sites at Mrauk U. This also means gingerly walking over surfaces littered with debris, which are obviously seldom cleaned.

An open-roofed linear passage circumnavigates the outer portion of the structure’s base. A column of metre-odd high stone Buddha statues is seated on raised pedestals in the identical mudra position, in shallow square alcoves lined along the lengthy passages. This is arguably the most impressive aspect of the temple.

The insets with the crumbling seated Buddha statues are set against matrices of Buddha figurines engraved on the stone walls, interrupted by dividing walls, the individual segments of the lengthy passages joined by low Roman arches. I am joined again by Ilaria and Ian, who knowledgeably discuss the architectural features of the temple and the manner in which they contrast against other styles of Buddhist architecture they have witnessed in the region. Dominique and Laurent briefly join us also, more sedate and less engaged today than they were yesterday.

The drama of the afternoon is heightened by a procession for the initiation of a young monk attended by the young initiate’s community. Each group of participants symbolizes a different aspect of monkhood, including the flags of the Buddhist religion, pots of flowers carried on the heads celebrating the beauty of the faith, a symbolic tree of money used to display the financial donations to the young monk, allegorical crowns implying the monk’s regal position in society, aluminum pots bearing branches of the Eugenia plant symbolizing victory on the heads of some women, and the books he will study carried on the heads of other women.

The tail end of the procession ends in disarray as one child’s symbolic golden crown falls to the ground, breaks, and resulted in tremendous distress for the child.

I continue to the large stone Buddha sitting erect at the Peisi Daung paya on the hillock shrouded in foliage, set against the darkened cumulus shreds. Laurent and Dominique make a brief appearance as Ian, Ilaria and I inspect the small structure. A trio of enthusiastic young Germans sit poised atop the upper rim of the stupa, engrossed in a childlike conversation with a handful of young goat herders, an ebullient confluence of innocence and romanticism.

Ian is parched and needs to leave, and after a brief interlude with the Germans as to the places they have visited and why they are so great, I continue back to the northern group to catch the last rays of sunset over the dispersed temples.

A guide explains that at a different time of year, from a perch behind us, the sun sets ahead of the most spectacular of the temples.

Beyond collecting a few marian plums from the tree behind Andaw paya, motivated by the promise of the burst of sweetness yesterday night’s rains may have brought, it is time to return to Shwe Moe and take in the proprietor’s raucous and seemingly pointless yelling, although eventually she deflects again, claiming the bus transport manager has stepped out for a while.

The evening’s excursion leads to the periphery of the market area, where sadly next to no fruit is available. The young Germans from Peisi Daung are now engrossed in the sweet and savory offerings of a set of vendors on one street corner, the young woman dismissively telling me that they only eat on the street, and never go into restaurants, proclaiming the vaunted privilege of serious travelers. The presumptuousness of the backpacking crowd can sometimes be nauseating …

Meandering further down the street along the apparently lifeless enclave to the rear of the Royal Palace, I encounter a tall American from New Orleans, who can’t promote the merits of the Kaung Thant restaurant behind us enough. It is probably brimming with clientele for a good reason!

An extravaganza of curries and side dishes is served at our table, and true to his word, the fish curry is remarkable, the dense, meaty flesh of the ocean fish reminiscent of sea bass, the oily curry sauce itself prepared with some combination of onion, garlic, mustard seed, chili and mango pickle, the result a fragrant, hot, spicy and largely elusive cocktail of flavour. The chicken curry, baby aubergine stewed in pork and chick pea flour, pickled mango salad and other side dishes don’t disappoint, either.

The night comes to a close with a slow bicycle-born amble through the town’s nocturnal streets, revisiting the string of inexpensive guesthouses I had passed on arrival in town, the subsequent darkness almost overwhelming the potholed road and atmospherically-lit rambling bungalows hidden behind the trees’ darkened canopies.

The final destination is Swe Moe, where the matron is lying prostrate on an air mattress, watching an Indian soap opera, briefly commandeering her employees to produce my bus ticket. I am left even more mistrustful as to the authenticity of the ticket, given that it has been issued for the 29th of May rather than the 27th of April.

I can only hope and pray that I will not be met with blank stares when I arrive at the Sittwe bus station on the afternoon of the 24th.