September 17, 2019

The Alster lake is central to the city of Hamburg, and consists of two essential components – the Binnenalster, hugging the inner city, and the much larger Außenalster, which extends into the wealthy residential suburbs to the north. Numerous canals connect into the two segments of the Alster, the Alsterfleet canal connecting the Binnenalster and the Elbe, one of Germany’s great rivers. The river originates in the mountains of the Czech republic, and flows northwest through Germany, passing through Dresden, Dessau and Magdeburg before reaching Hamburg, ultimately mouthing in the North Sea.

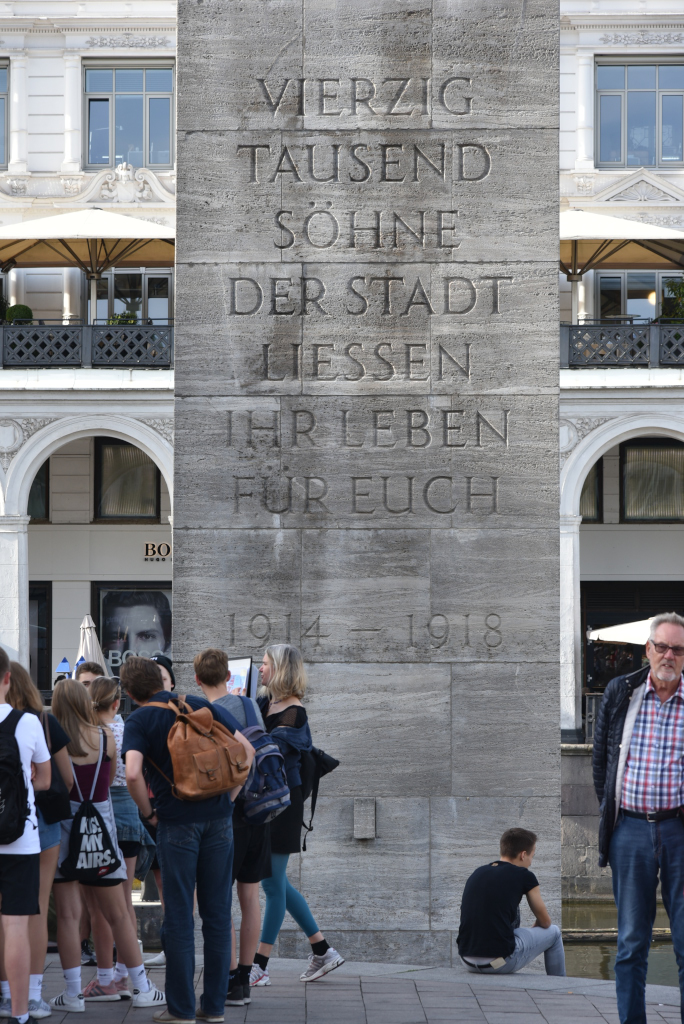

One of the central meeting places of Hamburg is the iconic Jungfernstieg, a series of terraces that run along the southern edge of the Binnenalster, and where the inner city meets the Alster. Some of the most prestigious department stores in the city are located on Jungfernstieg, although the bulk are located along Mönckebergstraße. The crowd I see on Jungferstieg today looks very peaceful, although apparently only a few years ago, the area was a staging ground for riots of immigrants and refugees.

In 1235, Count Adolph IV of Holstein commissioned the construction of a mill dam to use the Alster’s water for a local corn mill. The resulting mill pond turned out much larger than expected. The embankment along the newly created Lake Binnenalster was named Reesendamm, in honor of miller Heinrich Reese, who at the time operated the mill. During the 17th and 18th century, Reesendamm was enhanced and widened several times. With Hamburg’s growing international sea trade and the city’s status as a sovereign city-state, the elegant promenade obtained a cosmopolitan outlook and became popular for strolls along the lake front. Citizens of Hamburg accompanied their unmarried daughters out on a walk, looking for a suitable bridegroom, leading to today’s name of the promenade: Jungfern (i.e. maiden), Stieg (i.e. stair, walk).

The Bleichenfleet canal leading to the city hall is the pinnacle of luxury, the tables of adjoining elegant cafes crammed into the the little available space. But this being Europe, no one is particularly concerned about the lack of space or accessibility for pedestrians trying to navigate the narrow passage. The whitewashed walls flank the colonnaded passage, a succession of rounded arches underlining the evocative quality of the gallery. The cramped urban environment opens up to the squares located around the city hall, whose massive volume overwhelms the entire surrounding area. The plazas provide the space for performers of all sorts, and the continuous flow of humanity there to take in the spectacle of entertainment, people-watching and spectacular architecture.

The Hamburg Rathaus (City Hall) is the seat of the government of the Free and Hanseatic City of Hamburg, one of Germany’s 16 state parliaments. After the old city hall was destroyed in the great fire of 1842, it took almost 44 years to build a new one, the present building designed by a group of seven architects, and completed in 1897. Built in a period of wealth and prosperity, in which the Kingdom of Prussia and its confederates defeated France in the Franco-German War and the German Empire was formed, the look of the new Hamburg Rathaus was intended to express this wealth and also the independence of the State of Hamburg and Hamburg’s republican traditions.

The stunning neo-Renaissance building is massive in its volume, overwhelming the buildings in the surround area. It features a total surface area of 17,000 m2, not including the restaurant Ratsweinkeller, now called Parlament, itself 2,900 m2 in size. The tower is 112 metres high with 436 steps. The balcony is surmounted by a mosaic of Hamburg’s patron goddess Hammonia, the city’s coat of arms and an inscription of the city’s motto in Latin: “Libertatem quam peperere maiores digne studeat servare posteritas. (“The freedom won by our elders, may posterity strive to preserve it in dignity.”)

The Alstadt (Old City) unfolds to the south of the Rathaus, the narrow alleys and canals home to a mix of different architectural styles. The stark modernist glass structures reflect the imperious decorations of the city hall, while the neo-classical structures feature their own richly embellished facades, including decorative supporting brackets, arched doorways, period lamps, elaborate casements, and arched windows.

The canals that weave through the Altstadt amplify the sense of mystery of the area, bridges deftly arcing over and along their perimeter. Vistas of the cramped area open up over the water, providing superlative views of the intriguing buildings and the counterpoint of different styles around me. Glass provides a mirroring effect, and while the topography is flat, the sense of perspective alters considerably by either rising onto the bridges or for that matter descending to the water’s edge.

A showpiece in the neighbourhood is the Hindenburghaus, named afer the World War I military commander and president of Germany in that period. The building features an elegant sandstone façade and a magnificent entrance hall. It was built in 1909 as a hotel, although just a few years later the Hindenburghaus was being used for commercial purposes. These days, it is considered one of the most beautiful office buildings of the Gründerzeit period, which was responsible for characteristic architecture for many of Germany’s cities in the years of rapid industrial expansion in Germany at the end of the 19th century.

Closer to the river, the elegant commercial – and to some extent residential – district largely marked by the ostentatiousness of the Gründerzeit – gives way to modernist commercial behemoths, the overarching sensibility morphing from elegance to that of functionality. The area caters less to hospitality, although there are some wonderful examples of bars and restaurants to be found in the area, sandwiched among the massive structures. Whitewashed facades are replaced by brick, and the northern German Renaissance style becomes more apparent.

In the end, the relative modernity of the buildings around me is deceptive, inasmuch as Hamburg is far older than any of the architectural evidence demonstrates. A clue is provided of the statue of Saint Anschar, Archbishop of Hamburg-Bremen from 834 to 865 A.D. The sightlines open up as the canals expand to lagoons, now close to the Elbe, the little amount of green visible almost a shock to the eyes in this highly compacted area of the old city.

My final destination of the day is the Speicherstadt, the intriguing warehouse canal district in the heart of the city’s port. What should seem like a relatively characterless area is rich in charm and mystique, given the winding waterways, the stern red brick structures with subtle decorative flourishes characteristic of the low countries, and squat barges both commercial and residential in nature. The boats have been reclaimed as living quarters rich in whimsical embellishments, and contrast against the sleek modernist buildings inserted into the swath of red brick and industrial port installations which serve little more than decorative purposes in today’s era. Metal bridges swoop over the canals to offer varying sightlines of the sea of red brick and water below.

The Speicherstadt is a major tourist attraction in Hamburg and is the focus of most of the harbor tours. It includes several museums, such as the Deutsches Zollmuseum (German Customs Museum), Miniatur Wunderland (a model railway) and the Hamburg Dungeon. It is apparently the largest warehouse district in the world where the buildings stand on timber-pile foundations, and in this case, oak logs. It is 1.5 km long and intertwined by canals (‘Fleeten’ in low German), arcing around the inner harbour facing the Elbe river. The Speicherstadt district was built from 1883 to 1927, originally intended as a duty-free zone. More recently, it was awarded the status of UNESCO World Heritage Site on 5 July 2015.

(Narrative excerpted from Wikipedia)