March 23, 2018

There is nothing like the luxury of being able to spend the morning writing in my spacious and quiet room. The sun washes over the terrain of this luxurious hotel, sprawling from the manicured lawn area to deep in the forest. Various types of pink and red hibiscus flowers peer out from the trimmed hedge running alongside the staircase leading up to the reception building and restaurant. The breakfast is somewhat canonical in the country, but the setting and the views are not, concluding with the excellent coffee served here.

Today’s agenda includes El Tablon, La Chaquira and Purutal, all en route to Obando, which I am of the mistaken belief that I can comfortably start out to visit as of the early afternoon, particularly given that I will first have to get to town. The shuttle that runs from the archeological park to the town centre does not appear as promised, and so I walk down to the gorgeous Altos de YerbaBuena restaurant, which is a definite possibility for later in the day, although given how my chaotic adventures unfold, I shouldn’t be committing to too much for the coming evening.

The shuttle does finally arrive, depositing me in front of the Café Chapará for one last excellent coffee and the purchase of some of their highly aromatic beans. My strange turns of conversation leave the staff somewhat perplexed and bemused, although the employee originating from the llanos does hesitantly show me pictures of Villavicencio, his town of origin, Colombians from the region typically being very proud of their roots.

Up to the motorcycle taxi stop, and then uphill to El Tablon, which is a very straightforward road as long as we don’t branch off onto a dirt road, which quickly becomes treacherously steep. ‘No, no, I’ll walk the rest of the way’ I tell the driver cheerily, as it is not worth risking the integrity of the bike for the few thousand pesos. In any case, the site is just around the corner, a narrow gap in the barbed wire fence providing access to a steep slope, at the bottom of which lies one of the typical open-faced bamboo sheds containing several large, leering stele of the San Agustín culture.

The faces on the sculptures stare ahead blindly and impassively, the hands gripping some object, and in the case of one of the statues, splayed away from the body. The surrounding landscape is also dramatic, thick forest dotted with a few cabins, the effect heightened by the heavy cloud cover above. A brightly painted house with terracotta tile roofing lies immediately to the side, advertising itself as an ethnographic museum, although from what I can make out, it looks like nothing more than a family home looking to cash in on naive tourists. And the pleasure costs COP $5,000 …

And now off to La Chaquira along the winding country road with its dips and rises, the fenced fields on either side somewhat wild in nature, ridges of thick forest vanishing into the distance. One small coffee finca has invested a lot of effort in landscaping their plot with exotic flowering bushes, including a pink borrachero, heliconia and other plants I have never seen before. I descend towards the location of La Chaquira and am greeted by loud rock music that seems to herald from a different era, vaguely similar to the music I grew up with, but different.

And yes, the vendor of small stone sculptures assures me, the owner is Swiss, which makes sense, as the area seems to have been invaded by aging Swiss and German hippies looking for their taste of paradise. I proceed along the stone path towards an at first gradually descending drop, the stairs then proceeding to a path that begins dropping more steeply, culminating in a metal staircase that descends vertically towards a platform far below.

Views of the dramatic upper Magdalena valley unfold around me, some waterfalls cascading into the valley from the heavily forested cliffs that soar above this lower portion of the narrow valley that leads to the Estrecho above. Moments of contemplation ensue as I look out over the beauty before me, then I climb back up to the plateau above to make my way to Purutal, the next attraction, without realizing that I have missed one of the star attractions of the region, and that is the depiction of the female known as La Chaquira on a slab of rock looking out over this dramatic landscape. Oh well, there’s always the internet as fallback position!

I have to take some photos of the lulo plantation en route to Purutal, the fruit hanging off small woody bushes with broad leaves, the bushes planted at relatively close intervals, bearing apparently no more than a dozen of the matt orange round fruit individually, although it may also be that these plants are regularly culled and hence bear far more fruit than I can see at the moment.

My next destination is located at quite a distance, a concern particularly considering the dull leaden sky threatening to erupt as I trudge along the rocky dirt road rising further and further into the monte. I was intent on avoiding any serious climbing today, but since I am here, I may as well continue. Occasional views of the dark forest and crests of hills open up on the distant horizon. Of course, I haven’t really thought through how I will continue back to the area of San Augustin from Purutal.

The road appears heavily trodden by horses; riding to the more remote archaeological sites on horseback is definitely one of the attractions in the region, but given that I am not much of a horse person and probably too frugal, I am happy to be walking the route on my own two feet. Actually, I love walking in nature, and am very appreciative of being able to walk in the relatively remote and peaceful countryside, far from the air and noise pollution that afflicts even small communities in the country.

I climb up to a rise on which ‘La Purutal’ is scrawled on a sign, pointing to the right. Huffing and puffing on my way up the hill, I see some modest but atmospheric eateries set up to the left, and on the right-hand side of the dirt road, a huge stone gate set on the edge of a grass field, behind which is a small kiosk where a middle aged man is intent on collecting COP $4,000 as admission, although I suspect this money may not be going to any agency dedicated to the preservation of historical artifacts.

He entertains me with the usual rhetoric as to how terrible the country is, and is quickly interrupted by a younger cohort listening to a soccer game, the cheering to celebrate a goal blaring at full volume and preventing any possibility of conversation. Overhead, the heavy clouds threaten rain, the contours of distant hillsides receding in shades of blue-grey.

He leads me across the field to the location of the statuary that comprises the Purutal site. ‘The politicians take all of our money’ and ‘The politicians invest nothing in the people who live in the countryside’ he expounds, repeating mantras I have heard over and over here. Unfortunately, my responses wouldn’t do much to ingratiate me with people on the left side of the political spectrum.

If the government invested money in the people living in the campo, what economic benefit would be sustained by the campesinos and the country at large? What possibility exists of the campesinos becoming economically more viable as a result of some contained investment? Since when do politicians and bureaucrats not reward themselves royally for their efforts? And if you were so convinced that politicians live such a privileged life, why don’t you become a politician and reap the same benefits?

He tells me that many foreigners have bought land here, locals happy to sell their land and make for the city, where they can live happily ever after without having to work, or at least not too much. That may not be a bad idea, provided the foreigners invest money and effort into innovative businesses, and employ locals, treating them with respect and generous remuneration. On the other hand, if that doesn’t happen …

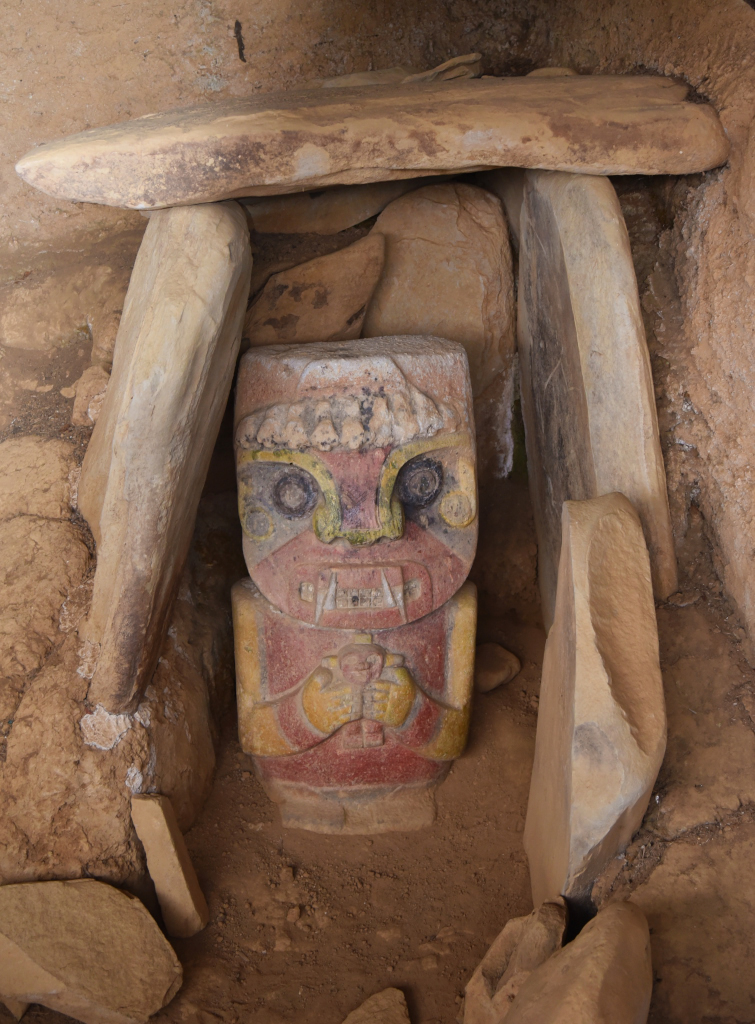

There isn’t much to this site, although the setting is very dramatic. The man leads me to a small statuary protected by means of a bamboo canopy at the far edge of the field, two figures side by side, the larger, leering figure apparently wearing a mask, while the adjoining figure is a combination of eagle and serpent, each representing different concepts. Further to the back, at the far end of a depression lies another larger canopied site, housing several figures that are apparently the only ones in the San Agustín region on which the paint is still preserved. Apparently the culture at the time had a fondness for bright colours!

He rushes back to the cover of his kiosk while the skies burst forth from their restraint, a light drizzle soon becoming heavier. Behind the second and larger statuary is a ramshackle house that turns out to be his, and on whose small terrace sits a beaming young woman, weaving some indeterminate fabric, beckoning me to join her. She evokes a fairy-tale image set against the painterly background of the crumbling building, the lush forest, and the daisy-like flowers and hibiscus, the blue-grey contours of the distant hills. But alas, I am not particularly interested in learning about weaving from her, much as I would love to spend time with her otherwise; it is about to really come down, and I may have quite the distance to cover before reaching the comfort of my hotel.

The small outpost across from the purported entrance to the archaeological site is well equipped with a handful of small tables, a stand on which a variety of snacks is arrayed and a refrigerator, the entire assemblage covered with a canopy. I join the man who collected the entrance fee as he heckles an older man wearing a felt fedora, impassively looking at us. ‘He served in the Korea War!’, he insists, repeatedly, continuing on to attribute other alleged wartime commitments to the man, although his motive is far from apparent. The older man grins briefly, but otherwise reveals little emotion, obviously not particularly pleased at the invective, although he doesn’t leave, either.

Apparently, his daughter, who owns the stand, also owns the modest accommodation at the back. The elderly gentleman owns a number of fincas in the area, hence is far from impoverished, nor is my host, who claims to have bought some 1,000 hectares of land in Putamayo during the years of conflict, even though things got worse in Putamayo than here in the south of Huila. Do you want 1,000 hectares of land in Putamoyo, he asks? They’re yours for free!

He changes his narrative from that of the politicians and moneyed classes exploiting poor Colombians. The people of the Chocó? They are limited by their own lack of motivation, as their region is rich in resources, and yet they don’t have enough to eat. The people in Boyacá? They remain poor since they refuse to cooperate and join forces, like the far more businesslike citizens of Antioquia. Our palaver flows freely, laden with humour, the older man remaining at the side, looking on impassively as if he hadn’t heard any of our lively conversation. The rain continues to pour, then later on slows to a trickle. It occurs to me that I need to continue walking, as I have little idea as to how far my hotel and the entrance to the Parque Arqueológico de San Agustín is – or even how to get there!

The man wants me to wait for him to close his shop, as he is also heading on foot to San Agustín, and so I do. We walk at a brisk pace, continuing to talk, myself soon dominating the conversation, but as we continue along the winding road, rising and falling, navigating the loose rockfall and potholes at a brisk pace, it occurs to me that we don’t appear to be nearing any evidence of civilization.

How far is the town, anyway? An hour from here? We reach a rise, and there it is, at a considerable distance, and yet it is also well after 6 pm, and it will be dark well within the hour. And I am not heading to San Agustín, rather at a hotel located near the entrance of the Parque Arqueológico de San Agustín. I am getting a sinking feeling, as the light has fallen considerably, and as I turn onto a path that will allegedly take me to the entrance of the main archaeological zone, it occurs to me that I have no idea as to how far away it could be.

I have a sinking feeling that this is not going to turn out well. Dusk is setting in, and the shaded areas, the road is even darker. Every turn, every rise, my hopes sink even further. San Agustín is far off in the distance, I can count the minutes until darkness sets in, and I may well be miles from anywhere, never mind my hotel. I trudge onwards, wondering how I will get myself out of this situation. Then at the back of my mind is the lurking consideration that this area was only really secured in recent years, and the idea of a foreigner wandering around mountain roads in the dark may not be such a great idea.

Just as nighttime inevitably sets in, I see two young men approaching in the distance. Is the entrance to the archaeological zone close? Yes, it is some 15 minutes down the road – but it is closed now. Why do you want to go there?

I continue, and soon see lights of houses, which at least is encouraging, although I really could be anywhere. More lights, the darkness, the dirt road illuminated very marginally by the new moon screened by haze. Not being able to see the road, I stumble as my feet trip on rocks or potholes, my frustration growing as it gets darker and darker. The few parties I encounter sitting or standing next to their houses confirm that I am still on the right road – and yet I don’t seem to be getting anywhere, and it is just getting darker and darker.

It is now nighttime, and I seem to be nowhere near my destination. I have no light, as I rushed out the door of my hotel room on a very late start. Being sure that I would not get cold today, I failed to even take a light rain jacket, and with the heavy rains, the temperature has dropped enough for it to be chilly.

I reach what looks like an intersection, and yet can barely see the road. I flag down a motorcycle that approaches from behind me. ‘Where am I?’ I ask. and how do I get to the entrance of the archaeological park, anyway? The driver offers to take me where I want to go, which I momentarily think of refusing, then reason takes hold of me, and I agree. But I am not going to the hotel or to the archaeological park, but to the Altos de YerbaBuena that the manager of the Hotel Huaka-yo recommended so highly earlier on.

The romantically-lit restaurant with exotic plants laid out in front evokes a sense of comfort inside, what with the tables laid out with wine glasses and cutlery, the cabinets brimming with wine. No customers are present other than a young German couple seated at a table covered in a checkered tablecloth, engrossed in conversation. The menu looks promising, although the prices are not high enough to warrant any degree of optimism.

I am proven very wrong when dinner arrives, the grilled pork chops amended with a honey orange sauce, a separate rhomboid-shaped ceramic plate served with buttered mashed potatoes and another with an amazing salad preparation, the dressing honey-mustard, the parsley itself providing a potent flavour counterpoint, what with its traces of chervil and rue. There is more to the spicing used to create the dishes, and the overall effect is unique if not astonishing, building on the fundamental components of Colombian cuisine, and bringing them to another level. The owner’s vision is profoundly refreshing, given how utterly mediocre much of the food in the country is.