April 24th, 2015

Five in the morning is never an easy time to get up, and it certainly is not today. But there is only one single ferry a day to Sittwe, and so I have no choice. I belatedly pack my things as the motorcycle taxi driver waits for me patiently. Once at the jetty, he wants a hefty supplement for his wait.

Crowds of passengers flock to the jetty with the intention of crossing the two shaky wooden planks and boarding the vessel. The manner in which the young men attempt to balance while rolling their motorcycles onboard is somewhat frightening. In the end everyone, including the little grannies surrounded by their doting entourages, manages to board the ship safely and remarkably intact.

We are off at 7:05 am. A dense crowd of passengers is housed on two decks, the upper deck where I am seated divided into three ticket classes. The cheapest seats are at the front where there are no seats, followed by the seated area at the back, featuring red plastic chairs. The slightly reclined wooden deck chairs at the rear are the most expensive.

I have been placed at the rear, which makes sufficient sense, considering that I as foreigner am probably paying four times the local rate.

The almost exclusively local crowd is mostly peaceful, but the few feral individuals are relegated to the luxury section around me, the entire Indo-Burmese entourage unequivocally loud, from the young girls whose shrieking barely abates during the entire five hour journey to the older men seated behind me, either shouting and gesticulating at each other while chain-smoking or reduced to a pathetic hacking torpor.

On another occasion I may not necessarily care that much, but I am really exhausted and getting hungry as well, even thinking vaguely of getting out of my chair and clambering through the morass of people to the lower deck where I suspect some snacks are being sold. More important is that fact that my stomach, until recently quite tender, seems to be holding up well.

The flat green landscape remains drab most of the morning, interrupted only by the occasional collection of flimsy bamboo, teak and thatch structures, and oddly-shaped clouds billowing on the horizon, one particularly menacing beluga-like formation crouching over the pale mountains in the distance.

Plantations of fan palms used for thatch thrive along the shoreline. No agriculture is otherwise visible from the boat, which initially navigates along the narrow channel, the Keladan river gradually increasing in girth with every tributary that flows into it.

Very little in the line of boat traffic is visible on the river, although that may be explained by the fact that it is very early in the morning. The earliest phases of the morning are sprinkled with cool drizzle, although the passengers seem far more perturbed by the heavy winds building in the stretch of open water closer to Sittwe.

As storm clouds threaten overhead, the passengers’ bristling umbrellas seem somewhat counterproductive, given that the tips of the canopy simply conduit rivulets of water onto one’s neighbor.

The Keladan widens significantly with each tributary that joins the relatively short passage of the river, becoming a veritable delta by the time we enter the narrow canal leading to Sittwe’s jetty. Surprisingly modern recreational boats lie moored in side channels amidst the rusting hulks of the passenger boats and small cargo vessels.

The passengers on the boats certainly don’t seem very boat savvy. They throw garbage and spit overboard, which is thrown back into the faces of passengers behind them, never mind the people throwing up with the virtually indiscernible rocking motion of the boat.

As benign as our trip from Mrauk U on the Kelandan may be, another ferry takes passengers down the open Rakhine coast to Taungoo, not far north of Nagpali Beach, in what would most likely be much rougher water. In fact, one boat went down in bad weather with numerous passengers a month ago. Not that I imagine traveling in Myanmar in any way the paragon of safety.

Dilapidated warehouses with little sign of life and built according to somewhat more modern geometries range alongside sprawling teak and thatch structures set against clusters of bushes. The flat open land spreads out to the back, with no sign of urban space to be seen, and yet I am assured that the city is located immediately behind the foliage-shrouded channels to our left.

Just as the passengers crowd towards the steep staircase leading to the lower deck, and those from below clamber over the adjoining wooden fishing boat towards the jetty, expectant motorcycle taxi and tuktuk drivers glower in our direction from the jetty, eyes glued to their most lucrative possibilities, namely anyone who is obviously not local.

I let the hordes disembark before me, leaving me one of the last to leave. One driver plies me with his courtesies, but I think I would rather walk at this point after having been confined for five hours to this cramped boat.

Past the diminutive concentration of vehicles along the shore, a modest dirt road leads to the main street, running north half a mile into the centre of town, open water visible between the bushes a short walk to the west.

It becomes immediately apparent that the town is far more interesting than the travel literature has let on, not that the region has been particularly amenable to traveling for other reasons, including lack of infrastructure and perennial instability.

Broadleaved trees enshroud modest teak bungalows recessed on small, dirt-paved lots. The second floor verandahs are enclosed with maze-styled balustrades stained in blue, while shade-bearing tropical hardwoods weave along the alleys emanating to the side of the surprisingly well-paved boulevard. Symmetrically-patterned fascia line the gable ends of Creole-style villas unseen elsewhere in the country, lending Sittwe a somewhat otherworldly feeling.

Closer to the centre, a more mouldering sense of modernist architecture reveals itself in the modest grid of streets, a series of bank buildings signalling the definitive presence of money, although the hotel situation in town is of more importance to me at the moment.

I had found only a few hotels online for Sittwe, and their reputation is about as terrible as their prices high. The KSS guesthouse recommended by the tuktuk driver at the boat is a case in point, $30 U.S. being charged for a small box with mouldering walls and dark hallways on an upper floor, with tiny beds, thin mattresses and threadbare sheets, a token night table and rickety chair, moth-eaten mosquito nets, and a minute dank and unsavory bathroom.

Opting to look elsewhere, I come upon another much grimmer option on the main road for only $20. With such deplorable lower cost options, I can’t imagine the more expensive hotels representing such terrible choices.

I seem to recall that the Noble hotel had terrible reviews, and while it is expensive at U.S. $50 a night, its presentation from the tiled lobby, with large clean glass windows and a stained teak reception counter, gives an upstanding impression. An artful curving staircase leads to the upper floor, the carpeted floors and wood-paneled hallway leading to a small but equally impeccable carpeted room, with two very small but equally impeccable beds. The room also includes a small table, chair, fridge, nightstand, air conditioning, high ceilings, and apparently even wifi, all spotlessly clean.

It may be far beyond my normal price range, but unquestionably preferable compared to the places I have just taken in. And even better yet, the gargantuan cultural museum is virtually across the street, so this can’t be the worst area of town, not that Sittwe appears that shabby to begin with.

The Hotel Memory should be my last stop, except that the instructions provided by various locals send me along the muddy but atmospheric side streets running past the market area to the commercial harbour on the open sea. The expansive road runs closer to the sea, leafy, with large commercial and governmental compounds, and the new Strand Hotel I had heard rumours about online appearing before me in all its glory.

The Strand definitely has a very presentable room for $50 a night, but only for a single night, hence a stay wouldn’t be warranted, not that this locale shares the history its affiliate in Yangon reflects.

But the Hotel Memory turns out to be the undisputed winner in the hotel competition, an immaculate modern business hotel with slight artistic touches, polished tiles, burnished teak, ample furniture, high ceilings, similar to the Noble, but much more spacious and even more pristine. The staff eagerly show me to the smallest room I had booked, definitely quite satisfactory, but the superior room for $5 more a night is virtually a suite, and an absolute winner in the search, whose selection would be warranted anywhere, not just with the logic of being acceptable for Myanmar.

The staff downstairs warns me about the bus company I have bought a ticket from in Mrauk U. While their buses do run, the company is not that great, implying that they have earned the disregard and enmity of locals for a reason. I am about to find out how bad things are when I amble off to the bus station later on.

On my first bout of freedom in Sittwe, I can’t resist pulling out the camera and taking copious amounts of photos of this newfound architectural wonderland. Many properties feature unusual fencing made from sheets of metal punctured by rows of evenly spaced holes connecting stone pillars.

Bicycle trishaw drivers young and old wait for passengers expectantly by the roadside abreast the various institutional structures lining the main street. Vaguely-tended flowering gardens divide the mouldering colonnades and somewhat dilapidated shuttered structures from the relatively even pavement. The Shwe Tha Zin hotel looks fancy from the outside despite the exterior cladding of connected poles hinting at a current renovation taking place.

Several young men artfully roll and slap balls of white dough into the small pancakes to be griddled into parathas later on, much happier than the typically morose if not outright suspicious locals visible on the street.

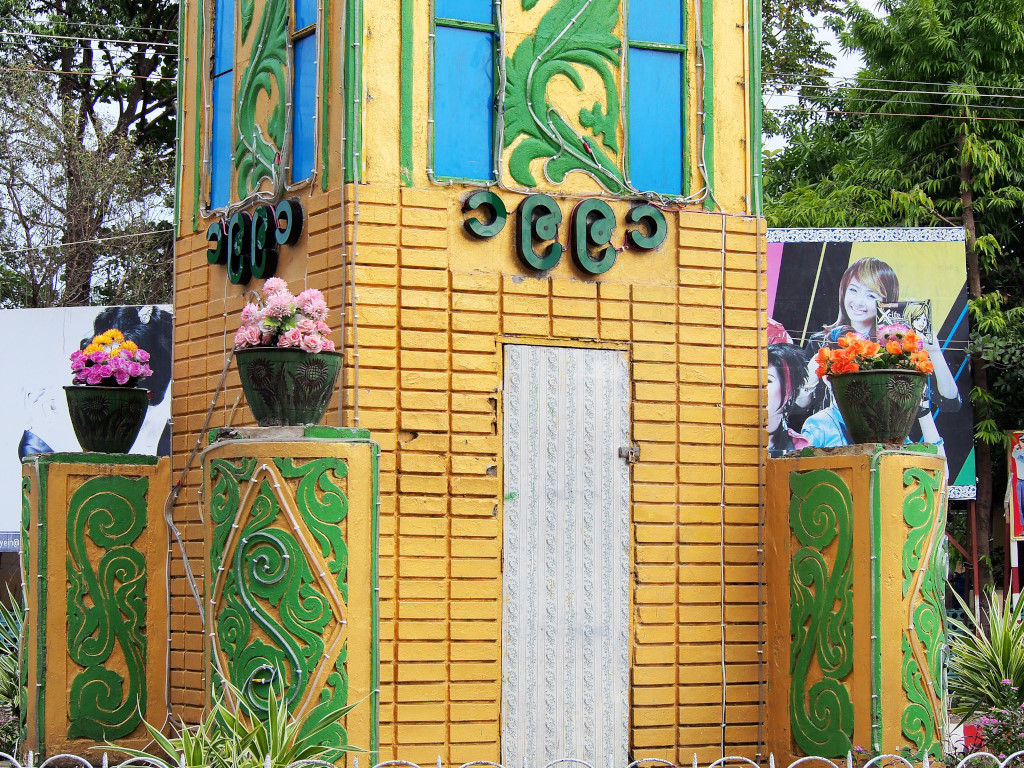

A tall fluted clock tower in bright gold, green and blue heralds the southern end of the main road. Imaginatively inflected embellishments grace the mouldering linear geometries of Modernist institutional buildings, contrasting with the shambolic decaying teak structures with their darkened turgid verandahs, hinting vaguely at collapse and overwhelmed by flowering tropical flora.

Rolling into the bus station with my trusted assistant, the first stop is the bus company that I apparently bought the ticket from in Mrauk U. The good news is that the bus company exists, but that’s where it ends – the crazed woman from the Shwe Moe eatery in Mrauk U conveniently took my money – 4,500 kyat more than the ticket from Sittwe to Yangon should cost – and never bothered reporting the sale to the company in Sittwe. And no, she is in no way, shape or form the owner.

The phone number posted in front of the restaurant in Mrauk U is out of service, and the number the young man has at his disposal in Sittwe connects to the woman’s son, who claims he is away from Mrauk U and hence cannot verify the ticket sale, and can be of no further assistance. The agents have no record of my ticket being sold, but assure me that I could sit in the front left row of the bus.

I bought and paid an excess for the ticket for seat 19 – why can’t I get this seat? They refuse to issue another ticket, as they apparently have to account for the money for each of the tickets disbursed, but that also means that I could arrive early in the morning of the 27th and be told the seat they verbally promised me now may be sold to someone else.

As my friend spends hours arguing with them, eventually hauling the bus station warden to intervene back to the ticket office, the harangue continues even more loudly, but they will not relent. I can take a seat on the bus, and they will then collect the money from the woman in Mrauk U, although at that point I will be entirely on my own, in no way able to communicate with anyone, vulnerable to the possibility of her lying about having taken money from me and issued the ticket.

Of course, the question would be begged as to where I would have otherwise conjured the ticket from. What I find shocking about this incident and the extent to which locals have basically gone to the point of putting me in an utterly precarious position is that it utterly dispels the idea that Myanmar is a safe country for travelers, who can expect to be treated with honesty and decency. Of course, this is all just window dressing, given the horrors that await the people living in the northern part of the state.

The virulent refusal to be of any assistance to a vulnerable tourist, given that the bus company is probably beholden to the shenanigans of Shwe Moe, if not other ticket dealers, is fairly shocking. As an aside, it is far from surprising that the travel agent at the Prince Hotel would have advised them that no bus tickets were available, as the Manthitsar’s terrible reputation precedes it.

As upsetting as the experience at the bus station is, it is time to move on, tomorrow another day in which I should visit the police or tourist police to ensure that this farce doesn’t get out of hand on the 27th. I just need to be able to get a seat on the bus, and once we have cleared Mrauk U, I think I will be fine.

Of course, I will have been overcharged by 5,000 kyat and won’t in fact have a window seat on the right-hand side of the bus, but right now I just want to get back to Yangon and get out of the country.

A presumably modern golden stupa hulks over a sprawling lot close to the bus station, the dome illuminated, and the rest of the property deep in shadows, extending towards the older women selling leathery steamed corn, peanuts, fresh mandarins, and apples to visitors.

Inside, the stupa is entirely open, the ceilings frescoed in gold and red floral stenciling, concentric rows of gilt columns leading to the central pillar, altars containing statues of Buddha, and affiliated trappings of the faith. The outer walls are embellished with panels depicting the Jataka in stone relief.

Having eaten nothing more than a few coconut omelets in the earliest hours of the morning, it would seem appropriate to actually eat something at this point. Ambling along the darkened roads of town, the odd car and motorcycle passing by, it seems that the entire centre of town is utterly bereft of even the most humble eateries, although the lone River Valley restaurant is apparently the local paean to fine Arakhan food.

A coterie of seemingly wealthy diners occupy many of the polished wood tables. The restaurant is brightly lit, with smartly uniformed waiters moving easily amongst the tables. My expectation is that the tab will be quite high – and I am not disappointed. Moreover, the plates are fairly small.

Dinner includes the following (conveniently forgetting to take photos of the fine dishes):

- a salad prepared with diced reconstituted jellyfish, spiced with traces of mild green cayenne, crushed black pepper, fresh lime, lemon grass, cilantro, garlic and red onion

- a red curry prepared with pieces of ocean whitefish, dark jaggery sugar, red tomato, butter, red onion, and traces of red cayenne, garlic, lemon grass, curry leaf and cilantro

- a green curry prepared with chopped squid, green tomato, butter, turmeric-focused curry powder, red onion, and traces of green cayenne, lemon grass and cilantro

No long bicycle trip to the hotel is involved here – the hotel is located immediately around the corner, such a suitably posh place to conclude my stay in the country …