February 8th, 2015

An early breakfast, packing my things, and then off to the reception, where the woman graciously offers me a ride to the airport in the hotel’s van. Well I guess it’s the least they could do for me, given how long I stayed here! Except that the young man driving me to the airport had been told specifically that I need to go to international departures, not domestic departures, which is where he in fact drops me off. I drag myself over to the international check-in counter for Bangkok Airways, but then find that the moderately long lineup doesn’t seem to be advancing at all. Not only is there only one employee taking care of the check-in, but things are moving exceedingly slowly! The man occasionally leaves the desk to check with people in the lineup to make sure they are all going to Mandalay, but the wait continues. Is this what we paid the premium fare for?

The somewhat reticent man behind me in the Bangkok Airways check-in lineup is from London, on his first journey outside the country. He seems aloof when I speak with him but is more likely to be evaluating the things I tell him in a relaxed but somewhat taciturn manner, possibly also nervous about his venture into uncharted territories. We eventually board the ATR-72 and climb into the sky for a very smooth flight, my conversation continuing with the man of Nigerian origins about the nature of culture, the diversity of African music, the relationship between the former colonial countries and the countries they colonized, and differences between the cultures of African and Southeast Asian peoples.

Tourism may have brought immense wealth to Thailand, but has also reduced its culture to a commodity, which comes at the expense of the authenticity the traveler seeks. Having lived his life in England but visited Nigeria a number of times in his life, he misses the ribald and vibrant street life that is entirely absent from urban northern Europe, even though a city such as London may in theory be home to such a multiplicity of cultures. Incidental to the sprawling conversation we enjoy I chat with an older American from Detroit, surprised in the passion I express for his home state, telling me that Detroit actually has a lot of beautiful places, just that you wouldn’t want to be in the wrong areas, as it could cost your life. Yes, the Upper Peninsula of Michigan is very remote and pretty, but also very poor, the eastern coast of lake Michigan home to some very charming resorts, such as Southhaven, that I visited many moons ago on the single foray into that area.

The introduction to Myanmar begins in the airport, the landscape around the airport empty, the tarmac empty, the airport virtually empty and largely unlit, a few immigration officials self-importantly guiding us through the immigration process, not that there is much to guide us through. Once we have picked up our luggage, a handful of taxi touts throw themselves on us. They hover over me as I withdraw money from the ATM. On one hand, I am not worried that anything untoward would happen, just that crowding someone at an ATM is very bad protocol.

The Englishman, a Swiss-Belgian couple and myself crowd into one of the long taxis leaving the airport along the largely empty paved road through the parched and deserted landscape, almost ¾ of an hour passing before we reach the confines of the city. It baffles me as to why the airport would be so far away from the city – are they expecting rampant growth here? Conversation now turns to my francophone neighbors, motivating them for their brief excursion into the country, although I am hardly that motivated myself – I would happily just hang my hat in some cafe and surf the web … and traveling in Myanmar will be anything but that! All those wonderful cafes found in Thailand will be virtually nonexistent in far poorer Myanmar.

Into the city, now deeper and deeper, the dilapidated poverty slowly morphing into somewhat more ostentatious commercial architecture, then the walls of the moat-ringed central fort, probably the only part of the city that I remember from before my visit almost 20 years ago. We are deposited at our respective hotels and continue on our separate paths, the Fortune Hotel I check into in the middling business area to the west of the train station, modest, my room small, with shared facilities, but very proper, clean and functional, not least of all because of the ongoing cleaning I make note of in the hallways.

Walking along the tranquil boulevards of the city, I navigate northwards along the small shops and occasional street vendor, locals smiling in greeting, not that I could do very much to respond, Burmese a completely unknown language to me. An excellent coffee at the bakery and cafe, and then I continue along 26th street in order to skirt the train station, a heavily trafficked boulevard replete in noxious exhaust fumes running along the southern boundary of the enormous fort complex. Much of the mid-range commercial architecture drops off east of the train station, the effective centre of the city far more residential, with sprawling bungalows of the wealthy interspersed with occasional modest shacks, nothing memorable standing out about the city, certainly nothing coming to mind about my visit to the city beyond the walls of the fort.

The razor wire and broken glass topping the walls of the wealthier mansions says enough about the place, at least regarding the disparities between rich and poor and security that the police state is not providing. I stop to frame photos of the eight story building being built very much by hand, the tiny dark Burmese clambering over the bamboo frames several stories up, stopping to look at me with fascination. Mandalay really does win the prize for looking forgettable, somehow reminding me of Khartoum for its bleakness, but perhaps because we are well into the dry season – not that the city of Chiang Mai I just came from is so memorable.

I could say that the streets here are somewhat untended but not really much worse relative to the perennially slovenly Southeast Asian countries, urban spaces in Thailand being marginally more presentable than other countries. What is definitely a change from Thailand is the garbage strewn on the ground and the smell of sewage and fecal matter that abounds. Given the rectilinear street pattern and the fact that both north/south and east/west roads are numbered incrementally, addresses typically being composed as ‘on x street, between y and z streets’, it would appear difficult to get lost.

Traffic is nothing like in Thailand, the empty streets almost begging for more activity. And also unlike Thailand, I see almost no tourists on the ground, despite the substantial number of generic Chinese-styled mid-range luxury hotels. The general area around the train station on one hand is home to relatively upscale hotels and shops, but the immediate area is quite squalid. What stands out here is the abject misery of the very poorest as well as the fetid stench you would never pick up on in Thailand.

I notice both men and women wear the beautifying thanaka facial chalk typical of the Burmese. Men typically wear the longyi sarong. People are mostly quite small but I see a fair diversity, many more Thai or Chinese as opposed to the darker, smaller Burmese (or tribal ethnicities?), the poorer people not surprisingly the smaller, darker and presumably more poorly nourished. People are very friendly, but hardly to a staggering degree, and of course coming from the perennially friendly Thailand, it would be hard to take much notice. Many of the youngest are very friendly, but the older people are often contemplative, even fearful. I think opening the country up could be a very positive thing, but also a question of abandoning the devil you know.

My march across the city of Mandalay is intended to reach the tourism office, which following a lengthy trek turns out to not even be in the location the young woman at the hotel reception indicated. Now where could it be … in the reception of one hotel, I am told it is located on the street in the direction I have just come from. I am sure I saw nothing along the lines of a tourism office from the road, but I should just retrace my steps and see if I can find it. It should be in this area due to the preponderance of fancy shops and boutique hotels.

I certainly would expect the Myanmar Tourism office in Mandalay to be quite a posh affair, but am shocked to reach the designated location and see a dilapidated wood shack in a tranquil yard, with a few locals lolling indifferently at the back. Even better, the building is entirely shuttered. This can’t be it! I stop a man mounting a motorcycle in the yard, asking him whether this can be the tourism centre. Yes, it definitely is, and he works there, but is going home now. ‘This early?’ I exclaim. ‘Yes’ he responds, ‘after all, I have been here since the morning, and we are supposed to be closed on Sundays.’ Whoops – he’s right, it is Sunday! But since he is still there, perhaps he can help me now. The important questions regarding which areas of the country I can visit he answers easily – I will have no problem getting to Myitkyina or Sittwe by bus, boat or train, as they are entirely open now. However, I cannot travel beyond those areas, not that I want to.

Walking along 66th Street, the road that runs along the eastern boundary of the fort, I am taken by the sense of emptiness, solitude and space of this city, the fort a gigantic anchor in the city but also very much a neutralizing force. The moat surrounding the fort is broad and still, small, red stone stupas appearing at regular intervals behind the crenellated walls. Near the eastern entrance of the fort motorcycle taxi drivers shout at me, but I have heard it all before, and even though there is still considerable distance to Mandalay hill, I would prefer to walk the distance to get a sense of the city and its visual narrative.

It is possible to visit the inside of the fort, but the soldier at the gate tells me the interior grounds are already closed for the day. I keep walking along, taking in the hypnotic vista of the fort walls and moat, the occasional monk passing by and the traffic flowing slowly and noisily on 66th street. The afternoon is advancing and it seems unclear as to whether I will be able to get to the top of Mandalay hill this afternoon.

The base of the hill is lined with taxis and motorcycle tax drivers loudly promoting their services, which would hardly be of much use climbing up to the peak of the hill. I am not really sure what I am supposed to be looking for here; once my sandals are off, I begin climbing the long staircase to the top, each subsidiary flight interrupted by a platform with some devotional installation, the steady flow of individual travelers unamused by the lengthy climb, never mind the bus load of largely middle-aged Russian puffing on their laborious ascent. Sometimes one of the younger chalk-faced attendants calls us to purchase water or souvenirs, but otherwise the temple is quiet.

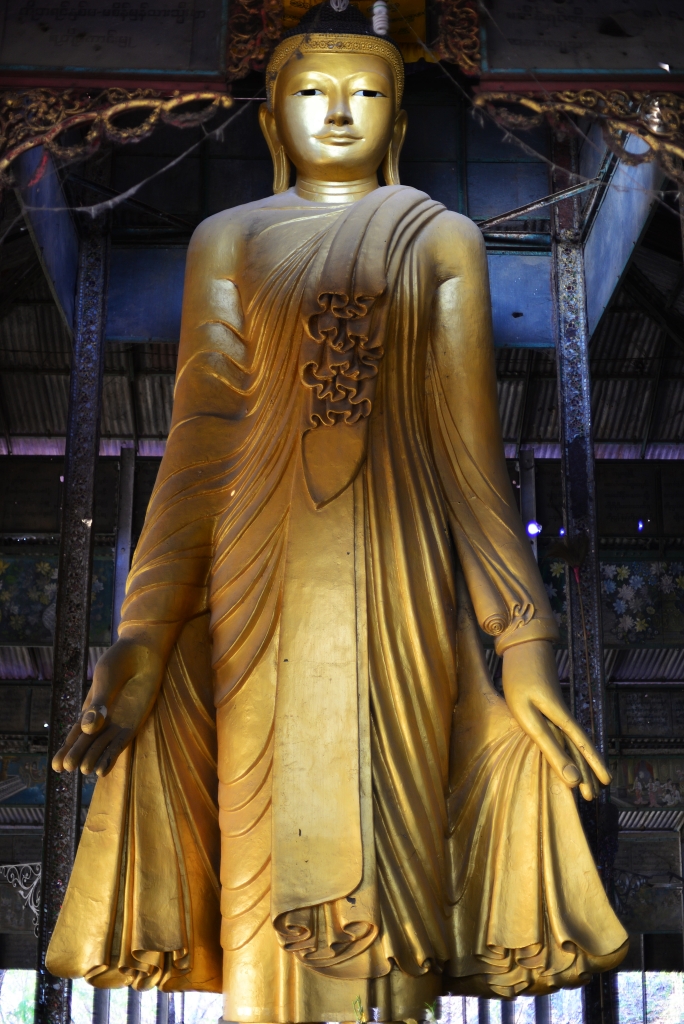

The staircases are covered with a staggered metal canopy lined with decorative fascia that I remember being characteristic of Burmese temples, not that this temple is remotely interesting, despite its alleged importance. Two giant golden Buddha statues are situated on the upper platforms, but the apogee concludes in a cavernous space filled with bamboo scaffolding and darkness, dogs wandering randomly through the shadows. Virtually no view is offered of the surrounding countryside due to the screen of trees surrounding the temple. Just beyond the concrete staircases and encasing bench seats, mounds of litter amend the thick carpet of golden leaves.

At the base of Mandalay hill, drivers call to me, but I keep walking, mouthing upon the road running along the eastern side of Mandalay fort. No, no, and yet again no I don’t want a taxi – possibly later on, but not now. The price for the trip to the far corner of the fort drops from 2,000 kyat to 1,000, then to 500, but no, I would rather walk a ways and get a sense of how the town looks in the evening. Then again, the east side of the fort faces largely private residences, although sunset over the fort looks quite magical, the walls and stupas prettily illuminated.

The Unique bar and lounge beckons, attendants greeting me at the gate, the posh quality of the establishment utterly incongruous with the general environment. Seeing the older English couple seated in comfortable wicker chairs on the verandah with a table full of beer bottles in front of them, I can’t help but think that a beer could really do me wonders to at this moment. She seems rather dismayed as I entreat her husband to an exposé on the wonders of English pop music, which he is only too happy to partake in, our passionate ideas on the last few generations of contemporary music resonating against the romantic backdrop of the nocturnal palace exterior.

Romantic at least to the young couples in silent embrace placed at regular intervals along the entire roadway, only to be briefly interrupted by motorcycle taxi drivers calling to me at the entrance, the young lovers again disappearing into the darkness. Now back along 26th Street, the traffic increases, one or two luxury hotels facing the fort probably commanding premium prices in town. It may not be boiling hot, but the Burmese are mostly clad in several layers of clothing, sweaters and jackets almost mandatory. The outdoor exercise equipment I saw on various occasions in Thailand is featured here too, a suitable playground for women and their young children, then beyond, more young couples in addition to young men idling in groups.

I continue my journey a few blocks to the south, meandering through the darkness and haze, the air thick with the smoke of charcoal burners, vendors huddling with their obscure wares in the darkness along the side of the road, the grimy jumble on their carts giving little idea as to the nature or incentive to consume whatever food they seem to be preparing. The increasing density of sprawl closer to the train station includes locally-styled eateries sprawled over fluorescent-lit terraces, the only concession to aesthetics the rows of indestructible potted plants lined against the roadside.

Invariably there are no English menus and no buffets or plates of half-finished foods to speak of, as everyone seems intent on drinking their sorrows away. At one station I manage to elicit a thick book of tatty, plasticized photos of food, but make the mistake of asking what the cost of certain dishes is, the waiters occasionally nervously looking in my direction as the thick crowd of locals busily imbibes at the other tables. But no one returns and I impassively move on, finally electing to enter some Chinese-style one-hit wonder, fried rice being the best I can muster.

February 9th, 2015

At breakfast, I meet a beautiful young Australian woman who is actually of American extraction, but her parents had her while living in Australia, then moved back to the U.S. All of her family lives in the U.S. but her occasional visits leave her with little desire to move back, something that would be difficult to justify coming from the east coast of Australia. She is very gentle and I am wondering how she will cope with the vagaries of traveling in a very underdeveloped country such as Myanmar.

A romantic meander up one of the shambolic north-south streets (albeit without my Australian friend), the broken pavement laden with chaotic cyclists, motorcyclists, cars, and small trucks, the dusty broad-leaved trees providing marginal privacy to the small workshops and shops selling a variety of merchandise, as well as modest eateries that probably would be best avoided. My ultimate destination is the post office, located on the other side of 26th Street, the attentive workers seated at their ramshackle, dusty tables shuffling back and forth amongst the stacks of tatty ledgers, happy to sell me a handful of utterly unattractive stamps as well as postcards for 100 kyat each on relatively cheap paper.

For 200 kyat each the vendors on either side of the entrance offer stellar postcards featuring one stunning pictorial of the country’s many attractions after the other. Naturally I can’t resist and purchase as many as possible, not that I have any intention of actually writing all of these – most of them will just end up stuffed in some drawer, to be occasionally taken out and act as reminder of some of the amazing places I have visited in my life on some dreary and dark rainy Pacific Northwest day. Her friend from inside the post office keeps the conversation lubricated with his faltering English and dogged persistence, keen to assist my own Burmese language needs.

One of the historic Buddhist temples that receives little in the line of attention from tourists is the Shwekyimyint Paya, located at the bottom of the Indian ghetto not far from the post office. A large crowd of locals is seated before an altar, flowing outward into the plaza beyond, listening attentively to the voice of the speaker, although I can’t make out a person speaking from my furtive glances towards the stage, and believe it may in fact be a remote presentation.

A golden stupa towers over the complex, which features individual pavilions, meeting halls, residences, and so on. A middle aged man beams contentedly in my direction as he rummages through the pile of samosas littering his small stand in front of an open pavilion with seated Buddha statues crested with gilt and elaborately sculpted wooden halos. Elsewhere in the temple, people pray in silence. Ancient trees loom over the buildings of the complex, some weathered with age, others newly refurbished. Young lovers touch each other hesitantly in one of the temple’s more private corners. Heavy columns separate the lengthy arcade leading to the northern exit of the temple, crested with a gold and emerald geometric pagoda, the perimeter of each tier circumscribed by a wave of stylized rearing naga.

The area is diverse and interesting, what with the nearby mosque, the crowd of standing and motorcycle-straddling parents waiting for their children to leave school, cell phones the focal point of everyone’s lives, the walls stained with oblique graffiti. The Eindawya Paya further to the west is even more removed from the affections of visitors to the city, the enormous golden stupa rearing over a broad plaza and smaller pavilions.

A collegial local feels compelled to guide me to the local sites, but as much as I would like to meet locals, it won’t be on this basis. On my first visit to the country I found myself falling into the hands of touts, which was actually somewhat uncomfortable, although I think years of traveling in Southeast Asia and especially northern India have hardened me immensely. Well, other events in my life also … Smaller cream stupas, viharas, and statues of bodhisattvas abound, except at one side of the temple complex I hear what sounds like an amplified soundtrack to a horror movie from a closed-off building. I am hoping that the monks are taking some time off and entertaining themselves, and that this is no surreal indoctrination exercise.

The area further to the west is more familial, modest, if not outright dirtier and more run-down, beginning with the sewage-laden canal that divides the city from the Irrawaddy. But I soldier on in the interest of discovering some possibly fascinating temples as per the travel guide’s recommendations. Foreigners are much less likely to be seen here, hence the reactions ranging from surprise, welcome, anxiety, if not outright shock. A folkloric wooden bridge crosses the still channel in the area of the Chanthaya Paya, clothes drying along the lengthy balustrades, men busily stacking empty oil cans from their track on the garbage-strewn lot separating the bedraggled temple from the polluted channel.

Another man is putting finishing touches to what looks like an elaborately sculpted gilt hearse, and inside the paya several older men jump to attention to essentially try and get some donations from me. Beyond the small chapel in which they are seated the usual golden stupa is set against a regal plaza. Further towards the riverbanks of the Irrawaddy, the reek of sewage abounds among the modest eateries with little to recommend for themselves, shaded by the canopies of the ancient trees, the boats berthing along the shoreline loading and unloading merchandise, to be collected and transported by the decrepit blue trucks belching black smoke into the air, no poverty or embargo any kind of obstacle for the energetic and hardworking Burmese.

Out of some outlandish fantasy rear the giant golden dragons guarding the bow of a huge catamaran-based hotel and restaurant, a three-storied teak structure ranging to the back of the ship, the top level an open restaurant, the lower levels presumably a hotel. While looking out over the vessel assuming the shape of the mythical Burmese karaweik bird, the young employees of the restaurant standing at the top of the staircase leading to the ship engage me in small talk, initially to garner my business, but then simply because so many of especially the young here are very curious and polite, if not extremely sweet by nature.

We recount trivia of our lives, less important the facts of our exchange than the sentiments attached thereto. I resist the temptation to board and spend lots of money, which would be fairly laughable, considering that I arrived here on ancient bicycle. A better place for me to stop and indulge would be the fruit stand on 35th Street some distance east of the river, with its offering of slices of melon, watermelon, mango and pineapple on ice, ready for the maw of the utterly dehydrated client such as myself, the woman surprised at the amount of her fruit I consume. But it is fresh, excellent quality, and at 200 kyat (U.S. .20) per generous serving, it will hardly put me in the poor house.

Upon arriving again at the Fortune Hotel, I see none other than the young Australian woman I met at breakfast, trying to get her iPhone to charge using the adapter she bought earlier on so that she can book a hotel in Bagan. Unfortunately, it seems the adapter is not working, or perhaps just not with her phone, and she is quickly becoming frustrated. She had found three guesthouses in Bagan that she would need her phone to check, and she wants to get this done prior to leaving tomorrow. All those little details that fly at you while you are traveling, what with the constant slippage that occurs, particularly but not exclusively in developing countries. She was considering wandering around the area for something to eat and a beer, but I caution her that most of what is found locally is not necessarily foreigner-friendly. Now too panicked, she has lost her appetite and interest.

The Indian restaurant I saw earlier on is closed, the young hotel workers tells me, but there is a night market along 84th street. I am not optimistic about the market, but I should at least give it a shot – there really won’t be many alternatives here. I ride my bike slowly along the fluorescent-lit market stalls of mostly clothing, large stretches of the street empty and without stalls, particularly between the book and magazine vendors, the amount of whose merchandise would seem to indicate that there is a fair demand for print media however humble it may be.

A sequence of humble stalls feature low bench seats on which clients sit hunched over a charcoal grill at which a variety of meat cuts are set out for grilling, the nature of the meat cuts somewhere between unfortunate and revolting, including liver, blubber, claws, paws and other parts of the animal body I really would not think about going near. More appetizing are the stands filled with a tight matrix of trays containing masses of gelatinous sweets, by no means offensive, and certainly more pleasurable than the idea of eating the neighboring grilled meats, but quite crude nonetheless.

I see a young couple eating at a table next to a buffet stand, for which they gladly provide me with a recommendation, although the food is as generally just oily and bland, nonetheless good value, with some variety, and not at all disgusting. I chat excitedly with the young Spanish couple from some town near Teruel in Castile about traveling through Burma, the contrast with Thailand, and all the remarkable experiences that India offers, although in the end it’s just the predictable backpacker claptrap about all the places you have knocked off your list, although the two are far from shallow. It is fairly apparent that locals seated at neighboring tables are listening in all-too-eagerly, attempting to glean some shred of wisdom that the privileged foreigners can offer.